(RNS) — On a recent Sunday in church, the officiating priest invited us (as he does every Sunday) to pray. We prayed for those you might call the “usual suspects”: for the bishop, for those in positions of political authority, for the recently departed.

But among those we also prayed for was “Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. – and for all the other saints … ”

Technically speaking, King is not a saint in any mainstream established Christian tradition. (The Holy Christian Orthodox Church, a relatively new denomination not affiliated with the global Orthodox church, has made him a saint.)

But his inclusion on the list of “saints,” however informally, at my otherwise extremely traditional Episcopalian church speaks to a wider trend in both religious and secular spaces alike: the proliferation of “secular saints.” These are people whose lives, ideals and – at times – martyrdoms have made them into ideological and spiritual leaders and models, reflections of lives we wish to live, or wish to be able to live.

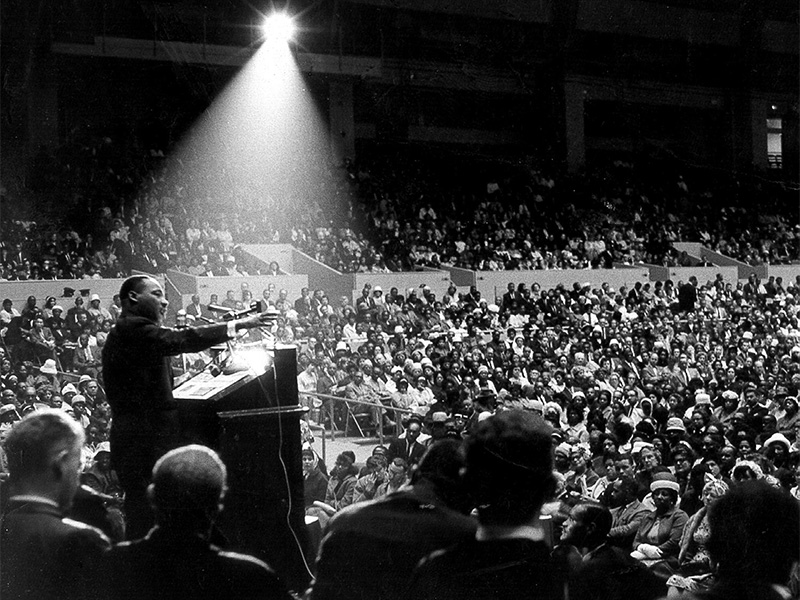

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks at an interfaith civil rights rally at the Cow Palace in San Francisco on June 30, 1964. Photo by George Conklin/Creative Commons

An ordained Baptist pastor, King is perhaps the most widespread example of secular sainthood: one who easily traverses the apparent secular/sacred. His quasi-sainthood has often been celebrated in Christian spaces since his death. Consider the website of the Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian Church, a social-justice-focused progressive church in Brooklyn, N.Y., which depicts King in the iconographic pose of a Byzantine saint.

But plenty of other figures have achieved similar stature wholly outside the Christian context. Oscar Wilde, for example, has become the de facto patron saint of the LGBTQ community. Nowhere is this connection more apparent than at the “Oscar Wilde Temple” – currently in residence in London – a mobile art installation by artists David McDermott and Peter McGough.

There, in a makeshift chapel saturated with Catholic imagery, Wilde’s arrest on charges of “gross indecency” (i.e., homosexuality) and his subsequent trial and imprisonment are depicted in paintings echoing that of a saint’s martyrdom, or of the stations of Christ’s cross. Images of contemporary LGBTQ martyrs, such as Harvey Milk – the first openly gay elected official in California, who was assassinated in 1978 – line the walls.

The “Oscar Wilde Temple,” by artists Peter McGough and David McDermott, is currently an exhibit at Studio Voltaire, which is in a converted Victorian chapel in London. Photo by Francis Ware, courtesy of the artists and Studio Voltaire

Visitors are encouraged to reflect on the meaning of Wilde’s life and work, as well as on his significance as a symbol of queer resistance. The space is even available for rent for gatherings – memorial services, say, or queer weddings.

If Wilde doesn’t speak to you, there are plenty more “secular saints” to choose from. The Unemployed Philosophers Guild, a company that sells memorabilia of historic intellectuals, from finger puppets of Wilde to Friedrich Nietzsche plush toys to tins of “Enlighten-mints,” stakes a claim for secular canonizations. The company sells a raft of “secular saint” votive candles, from Frida Kahlo to John Lennon to Harriet Tubman, resembling those used on altars in neo-pagan and Catholic folk traditions.

If you’re looking for more politically loaded saints, the online handcraft marketplace Etsy has plenty of sellers hawking “progressive saint” candles depicting St. Barack Obama, St. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Robert Mueller and even “Notorious” Ruth Bader Ginsburg, heralded as the “angel of everlasting dissent.”

Not everyone buying these candles intends to formally venerate their chosen icon the way, say, a Catholic worshipper might venerate a saint. But plenty do.

A writer and sex worker I interviewed for my upcoming book told me of the prevalence of folk magic rituals among sex workers she knew, many of whom choose to make candles devoted to, say, Anna Nicole Smith or Aileen Wuornos, on their altars in the hopes of gaining prosperity and protection. On a typical day, my source told me, she might place coins in front of Smith, whom she sees as a symbol of feminine power, to ensure a steady stream of clients.

Official congressional photo of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a Democratic representative from New York. Photo by Franmarie Metzler/U.S. House Office of Photography/Creative Commons

For members of marginalized communities in particular, figures like King or Wilde or Smith take on spiritual significance. They are not just inspirations but conduits or what in the church are called intercessors: figures who understand their supplicants’ personal needs and convey them to the higher power. Lighting a candle to, say, Ocasio-Cortez or Mueller might direct energy toward a specific, measurable end such as the indictment of Donald Trump. In this way, the “folk saints” of the marginalized become religious as well as political figures.

That, of course, is nothing new. Even within, say, the Catholic tradition, folk saints have long coexisted alongside the formally canonized, offering solace and miracles to those on the margins of society.

The folk character “Gauchito Gil,” an Argentine cowboy known for his work on behalf of the poor, appears on many Argentine Catholics’ altars. Likewise in Mexico for Santa Muerte, that country’s “lady of holy death,” whose cult is particularly widespread among the poor and those involved in crime – including sex work and drug trafficking.

Fan culture – with its vicious debates over “canon,” its obsession with relics and totems and its identity-forming reverence of its subjects – has always had much in common with religious fervor. From the devotees who make “pilgrimages” to Elvis’ Graceland or to the grave of The Doors’ Jim Morrison in Paris, fandom is a source of community, ritual and meaning.

Secular sainthood is ever-broadening to include celebrities and politicians alongside activists and folk heroes. Our public figures embody a modern sense of piety and self-sacrifice every bit as much as the ancient saints did for their times. A Martin Luther King Jr., Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez or Anna Nicole Smith may also carry many Americans’ desire for a radical reframing of our collective values. As a result we’re more willing than ever to blur the lines between “public figure” and “religious icon.”