(RNS) — I think often about the General Confession. It’s in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, used as part of the Daily Office: the one that goes “we have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts.” I wonder, often, how to wrestle with what that means; the sense that we cannot trust what we want, that — in the Emily Dickinson line infamously used by Woody Allen — “the heart wants what it wants.” Is what we want bad for us?

Or, to quote the Prophet Jeremiah, the heart is deceitful above all things.

Few of us would, of course, deny that we do want things that are bad for us. But the language of indulgence and sin, of desires perverse and unhealthy, is more often found in diet culture (“sinfully” good chocolate; devil’s-food cake; the virtue of abstemious eating and “clean” foods) than in wider conversations about morality. At most, the language of disordered desire is limited in religious contexts to sexual desire — a purity culture no less aestheticized, with white dresses and True Love Waits pledges, than that of wellness.

RELATED: Evangelicals perfected cancel culture. Now it’s coming for them.

In the secular context, desire all too often goes uninvestigated. More commonly we hear that our root desires can clue us in to who we “really” are; that any form of restriction or repression, or even internal conflict, is a vestige of oppressive social norms. Americans especially equate what we want, what we enjoy, what we consume with who we are.

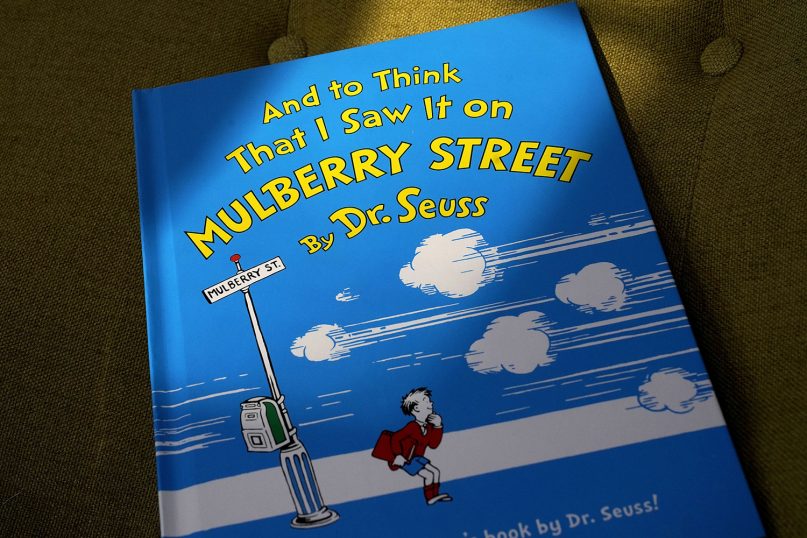

Which brings me to Dr. Seuss.

The debate over the supposed cancellation of Dr. Seuss over the past few weeks was the result of the Theodor Geisel estate announcing it would no longer publish several of the author’s minor works on the grounds of racially offensive content, and the subsequent decision of certain third-party sellers, including eBay, to ban those works from their platforms. That decision, and Mr. Potato Head, whose sexuality itself was said to be canceled, has already filled far too many column inches. I’m not here to weigh in on “cancel culture,” nor the attention-economy behemoth it feeds.

But questions of “cancellation” regarding problematic media properties — not problematic individuals — provide us with a way to talk about this very complicated nature of desire.

Sometimes the things we want, even the things we love, are bad for us. Sometimes we are attracted to ideas, or people, or even books, for the wrong reasons. Our own ability to perceive both the good and the bad, in the world and in ourselves, is all too easily warped by our own fallible cognition. A book we loved in childhood — a book we may even still love — might at once offer us solace and reflect, or even reinforce, morally noxious ideas: be they sexist, racist or other forms of evil for which we do not yet have a cultural vocabulary.

In the Christian context, the language of sin (and with it, of course, that of redemption and grace) does much to help us contend with these ambiguities. The vocabulary of fallenness, the idea that we can be simultaneously created in the image and likeness of God, and that our capacity for goodness and truth is warped by a fallen and perverted nature; the idea that we inherit blights on our ability to both know and do the good, and that we cannot reason or will our way out of these — all these are integral to Christian orthodoxy.

Indeed, it is striking that so many conservative Christians recoil in horror at social-justice-tinged language of “privilege,” or systemic racism — even as the Christian tradition demands that we contend daily with ways in which we are touched and shaped by evils we did not choose. We know as Christians that one fix for this is to deny ourselves what the world tells us to want.

RELATED: If we ‘canceled’ anti-Semitism

Yet capitalist culture all too often valorizes desire, and personal fulfillment, at the expense of mutuality or solidarity. Talking about how a beloved movie or book might be racist, or sexist, or offensive in other ways also offers us the opportunity to think more widely, and more seriously, about questioning and critiquing our desires. Why we enjoy what we enjoy — and what our enjoyment says about us — is a valid question. Investigating our enjoyment (say) of titillating images of beautiful women in sexual peril, or sadistically gory horror movies, is as valid as investigating our enjoyment of books that trade in racial stereotypes.

That is not to say, of course, that in cancel culture we’ve found an avenue toward redemption of secular culture. But as a corrective to a culture that makes personal desire paramount no matter how toxic, pointing out which culture touchstones we no longer approve or uphold shouldn’t just be a shibboleth in the culture wars. It should be an act of investigation in which we all take part.