(RNS) — Unless the Democratic National Committee moves the goalposts, New Age author and activist Marianne Williamson will be on stage for the party’s first presidential debate in Miami at the end of June. Last week, her campaign announced that it had received contributions from 65,000 separate donors, which is one of two ways to qualify (the other is reaching 1 percent in three approved polls).

You figure that a lot of those donors are people who have read one or more of Williamson’s seven New York Times best sellers or at least catch her on Oprah’s “SuperSoul Sunday.” She’s the first religious professional running for president since 1988, when Jesse Jackson sought the Democratic nomination and Pat Robertson the Republican nomination.

Jackson, the Baptist pastor, and Robertson, the Pentecostal televangelist, represented evangelicalism. What Williamson represents is metaphysical religion, a tradition defined by University of California-Santa Barbara scholar Catherine Albanese as comprising Freemasonry, early Mormonism, Universalism and Transcendentalism before the Civil War and, subsequently, Spiritualism, Theosophy, New Thought, mind cure and reinvented versions of Asian ideas and practices.

RELATED: The spiritual politics of presidential candidate Marianne Williamson

If Candidate Williamson has a predecessor it’s Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, who undertook to run for president in early 1844. This Easter, she explained her own move to politics in a live-streamed talk to a group of followers in Los Angeles:

You know, so often when we come to religion we think in terms of dogma, we think in terms of doctrine. But the spiritual revolution on the planet today — and there is a spiritual revolution — is a revolution of consciousness, as we all know. It’s not about doctrine. It’s not about dogma. But it is about where the human mind goes. And politics has everything to do with where the mind goes, because thought precedes behavior.

She goes on to place herself in the tradition of religious reformers who pushed for the abolition of slavery and women’s suffrage. “At the deepest level,” she says, America is engaged in “a spiritual contest” between demonic and angelic forces. “The separation of church and state is one of the most enlightened aspects of our country,” she says. “But the founders were not seeking to suppress religion. They were seeking to liberate and protect it.”

She concludes the talk with a prayer that ends:

We place in God’s hands our precious world. We place in God’s hands our country or our countries. In the name of all the great religious and spiritual figures, of all the avatar, and yes on this day remembering Jesus in his resurrection, one of the doors though which humanity has walked, may all humanity walk in the love that is center of our own true being, and thus may all be lifted, in this country and in our precious world. And so it is we say Amen.

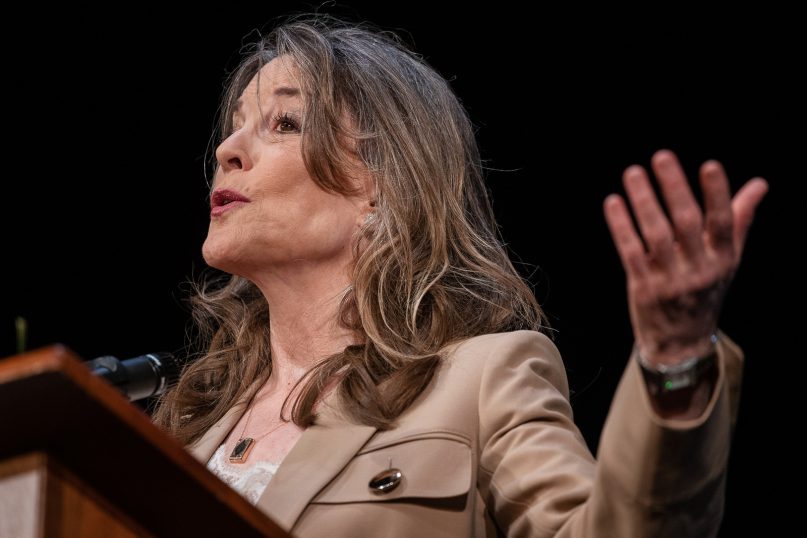

Marianne Williamson campaigns for president at the Sondheim Center in Fairfield, Iowa on April 10, 2019. RNS photo by KC McGinnis

The reference to “our precious world” is a tip-off that Williamson cares a lot about climate change. In fact, none of the Democratic candidates has advanced more far-reaching goals to deal with the crisis than she has, including Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, who has made climate change his number one issue. Rejecting the goals of the 2015 Paris climate accord as inadequate and going beyond the Green New Deal, she would take steps to recapture atmospheric carbon and reverse current warming trends.

This has caught the attention of climate activists, and earlier this month she engaged a couple of them, anti-fracking leader Josh Fox and my son Ezra, director of policy and strategy for The Climate Mobilization, in a wide-ranging discussion. “We have to re-sacralize the world,” she tells them. “And one of the things we have to re-sacralize is politics. Which is to say that we have to bring our sense of the sacred back into it. It’s insane what we’re doing to the Earth.”

Nor is it only on climate policy that Williamson is prepared to go where other Democratic wannabees fear to tread. Her ideas for economic reform are more radical than Bernie Sanders’. She advocates releasing as many prisoners as possible. She has not only embraced the idea of paying reparations to African Americans for slavery but has attached a dollar figure of hundreds of billions of dollars to it.

There may be something about metaphysical religion that opens the way for radical steps. Smith’s 1844 platform included the abolition of slavery, doing away with most prisons, open borders and freedom of migration, and capital punishment for public officials who refuse to assist those denied their constitutional rights.

And here’s something to wrap your mind around. If Williamson should somehow become the Democratic nominee, her opponent would also be an avatar of metaphysical religion.

Donald Trump’s religious formation came at the hands of Norman Vincent Peale, author of the 1950s bestseller “The Power of Positive Thinking,” which purveyed mind cure to a society beset by Cold War anxieties at the dawn of the Nuclear Age. Just as evangelicalism has its left-right polarity, so we might consider Williamson v. Trump the metaphysical equivalent of Jesse Jackson v. Pat Robertson.

Against Trump’s triumph-of-the-will worldview, Williamson embraces the ancient “organic analogy” that likens a healthy body politic to a healthy body. She does not now see our body politic as healthy. “I see someone like Donald Trump as a kind of opportunistic infection,” she says, “that could not have gotten hold of us unless there had been a weakened societal immune system.”

Correction: Mike Huckabee and Al Sharpton are (or were) religious professionals who ran for president after 1988. Huckabee, a Baptist minister who was president of the Arkansas Baptist Convention, ran in 2008 and 2016 as a professional politician, having served as governor of Arkansas. Sharpton, also a Baptist minister, ran for the Democratic nomination in 2004. Worth mentioning as well is 2012 GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney, who served as a bishop and stake president in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. While those are not precisely professional positions—the LDS church does not have a professional clergy—those certainly are positions of religious leadership. All of which is to say, another two evangelical polar opposites and an additional Mormon.