How many Jews died in the Shoah?

That is too easy. The number six million trips a little too lightly off our tongues.

How many of them can you name?

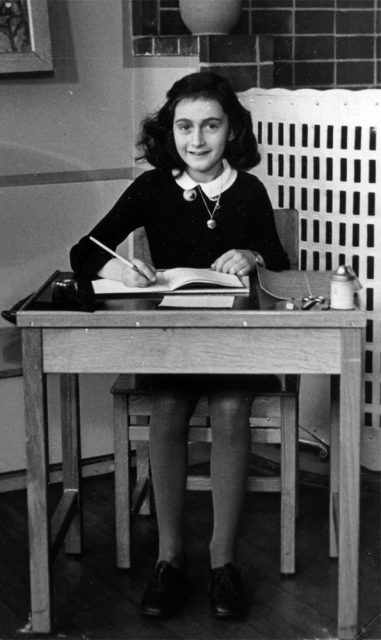

The only name that everyone knows: Anne Frank.

Had she survived, this week Anne Frank would have celebrated her ninetieth birthday.

This is impossible to imagine.

History has frozen Anne Frank in time.

She is the Jewish butterfly, fossilized in the amber of our memory.

She is eternally a teenager.

What was Anne Frank’s deepest wish?

I don’t want to have lived in vain like most people.I want to be useful or bring enjoyment to all people, even those I’ve never met.I want to go on living even after my death!

That is exactly what happened.

Anne Frank lived on. Not as one young woman, but as several.

What do I mean by that?

First, there was not one definitive version of her diary.

From the moment when her father, Otto Frank, the sole survivor of those who hid in the secret annex, discovered her diary upon his return to Amsterdam — Anne’s diary went through various versions.

Otto Frank picked up her diary, and he read it — and he did something — that word that we have heard so often recently.

He redacted her diary.

He edited out many passages: about Anne’s conflicts with her mother, Edith; about her emerging sexuality, especially where she embraces her bisexual longings.

Why?

Because Otto Frank was a German Jew. He was an assimilated Jew.

German Jews craved respectability and acceptance. Otto Frank was no exception.

He wanted to clean the diary up. He wanted to make it more acceptable to the masses of people who would read it.

Mr. Frank was not alone in his quest to find a “nicer” Anne Frank.

Fast forward to 1955.

Albert Hackett and his wife, Frances Goodrich wrote the theatrical version of the diary that opened on Broadway in that year, and which won the Pulitzer Prize for drama.

They were no strangers to the world of entertainment.

They had also written “Father of the Bride” and “It’s A Wonderful Life.”

Their version of Anne Frank’s life? One of almost eerie cheerfulness. They made her story less Jewish.

Then, along came a man named Meyer Levin. He wanted to restore the essential Jewishness of Anne’s story.

Why did America need this scrubbed-up, sanitized version of Anne Frank?

Because we could never have handled the truth about her final days.

This is how Cynthia Ozick put it:

One month before liberation, not yet sixteen, she died of typhus fever, an acute infectious disease carried by lice. The precise date of her death has never been determined. She and her sister, Margot, were among three thousand six hundred and fifty-nine women transported by cattle car from Auschwitz to the merciless conditions of Bergen-Belsen, a barren tract of mud. In a cold, wet autumn, they suffered through nights on flooded straw in overcrowded tents, without light, surrounded by latrine ditches, until a violent hailstorm tore away what had passed for shelter. Weakened by brutality, chaos, and hunger, fifty thousand men and women—insufficiently clothed, tormented by lice—succumbed, many to the typhus epidemic.

Fast forward to the 1970s.

There was an entire cottage industry of novels in which Anne Frank starred as a leading character.

In each of those novels, Anne has survived.

My favorite of this genre: Philip Roth’s dazzling novel, “The Ghost Writer.”

Roth’s literary alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman, visits an elderly famous Jewish writer in the Berkshires.

There, he finds a beautiful young woman living with the writer.

He imagines that the beautiful young woman is Anne Frank.

He imagines taking her away from the writer, bringing her home to meet his parents, who will then realize that he is in reality a good Jewish boy.

To have a son who has Anne Frank as a girl friend — who could ask for more?

There is one last way in which Anne Frank lived on beyond her death — in a story that some would even call sacrilegious.

A writer named Betsy Morais tells the following story about a woman rabbi of her youth.

The rabbi was Helga Newmark.

Rabbi Newmark has since died, and she had the distinction of being the first woman survivor of the Shoah to be ordained as a rabbi.

The late Rabbi Newmark told the children of her religious school a story about Anne Frank.

During the late 1930s, the Newmark family were German refugees, living in Amsterdam, a few houses down from the Frank family.

Their parents were friendly. Helga was three years younger than Anne.

Anne invited all the girls from their block to her birthday party.

“Everyone except me,” Rabbi Newmark said.

Then, she said the unthinkable.

“Anne Frank was a brat.”

In May 1942, the Nazis sent Helga to Westerbork, and then to Bergen-Belsen, and finally, to Theresienstadt.

She survived.

Something else survived — her decades old resentment of Anne Frank, that burned in her soul until the very day of her death.

Why would I share this story with you — this week, of all weeks?

We need to remember that Anne Frank was not a Jewish saint, and not a Jewish icon, and not merely a symbol.

First and foremost, Anne Frank was a child.

She acted the way that a child — yes, a precocious child — would have acted.

First and foremost, Anne Frank was maddeningly and wonderfully human.

But, in fact, Anne Frank never left childhood. She never survived adolescence.

Imagine Anne Frank at ninety.

Can you?

I simply cannot.