(RNS) — I was sitting in a master’s-level Christian ethics course at University of Notre Dame, listening to a presentation by one of my fellow students, when I heard him invoke Peter Singer, the Australian moral ethicist and a supporter of abortion rights.

“No one can take someone who argues for infanticide seriously,” I said with profound but unwarranted confidence, and more than a hint of frustration.

“The guy holds a chair at Princeton University,” the student replied. “He’s a serious figure whether we acknowledge it or not.”

He was right and I was wrong, but I would go several more years thinking of Singer as something close to a demonic figure who could only be used to show the horrific place consistent pro-choice reasoning ended up.

That changed when, as a doctoral student, I had the opportunity to teach an introduction to philosophical ethics course as an adjunct and I chose Singer’s 1980 book “Practical Ethics” as one of the texts. I hadn’t changed my opinion of Singer, but the book had a nice overview of the issues I wanted to discuss and I wanted my students to be challenged by his consistent rejection of the sanctity of human life.

My undergraduate training in analytic philosophy, as well as my view of what it means to be an authentic teacher, posed an additional problem for me to wrangle with: my attitude toward Singer’s work. My students led me to read him and teach him carefully and fairly. And as a result, I began to change my mind.

Though I would ultimately find a more theological way to articulate it, his argument for moral concern for nonhuman animals shook me from my dogmatic slumber on that topic. I also came to see how close his views on our duties to the poor were to the teaching of Roman Catholicism.

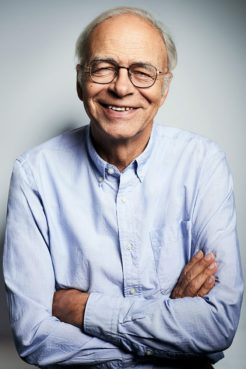

Peter Singer in 2017. Photo by Alletta Vaandering

Indeed, at the time Singer was just finishing his 2009 book, “The Life You Can Save,” which insists that we have the highest moral obligations to aid the global poor, personally, and through our own actions. If we fail to aid those who will die without our help, Singer argued, we are guilty of something like indirect or reckless homicide.

More surprising to me, I began to find his views on abortion and euthanasia more interesting.

Though I considered him clearly wrong about moral status and who counts as a person, he was wrong in interesting and informative ways. And, again, he was one of the few in his camp who was willing to follow his arguments wherever they led him — even if it was to a deeply uncomfortable place.

After I arrived in my current place at Fordham University, I began to think about a book project exploring Singer’s work, which would eventually become “Peter Singer and Christian Ethics: Beyond Polarization.”

Wanting to make sure I had Singer’s latest views correct before beginning this project, I wrote him an e-mail explaining who I was and a bit about the project, and asked about some of his views, expecting no response — in part because it said right on his Princeton webpage not to expect one.

Shockingly, a response came. A generous one. Singer, who also lived in New York City, suggested we get a (vegan) lunch and discuss. I was taken aback and somewhat starstruck.

But he was incredibly kind, curious and thoughtful. He knew the staff at the restaurant well, and I overheard him discussing a forthcoming meal he was expecting to have with the famed atheist and biologist Richard Dawkins there, in what I gathered was an attempt to help him along a journey toward veganism.

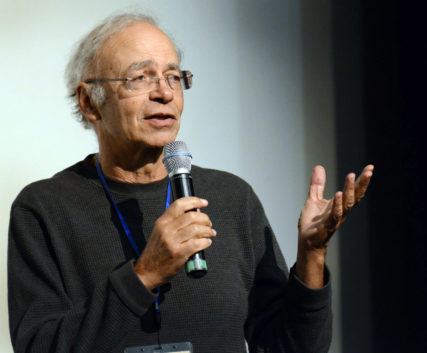

Peter Singer speaks at an Effective Altruism conference in Melbourne, Australia, on Aug. 15, 2015. Photo by Mal Vickers/Creative Commons

That meal was the beginning of what would become a decade-long friendship.

We have never papered over our differences. Indeed, as one does when one is an analytic philosopher, he honored our friendship by inviting me to debate him in various places, from his hometown of Melbourne, Australia, to his classroom at Princeton.

We also worked on major projects together. I’m deeply proud of the major international conference we put together at Princeton aimed at finding new ways to think and speak about abortion. It featured a genuinely diverse group of some of the best people in the world working on the issues, most of them committed to engaging constructively in good faith. (William Saletan wrote about the conference on Slate here and here.)

I was also very happy to play a significant role in a conference at the University of Oxford on Singer’s work organized by my friend and colleague John Perry, then of the McDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics and Public Life. Peter and I were the two presenters for the opening session, and I was so pleased to see high-level theological engagement with his work.

We did another memorable co-presentation at the headquarters of the Humane Society of the United States. At that event, where numerous HSUS employees asked him to sign tattered copies of his books that they credited with getting them interested in such work, I first learned that Peter had changed his mind about the relationship between traditional Christianity and the push for animal protection.

In the past, he had argued for a full-scale, frontal assault against the Christian churches that posited the sanctity of human life. Now, though he had not changed his mind about that ethic being mistaken, he was prepared to see such Christians as potential allies in the fight for animal liberation.

He had realized that the primary problems — consumerism among other matters — could be resisted together. Plus, Christians with orthodox Bible-based beliefs knew that animals belong to God, not to us, and that we are tasked with caring for them as the kinds of creatures God made them to be.

As I reflect back on our 10 years of friendship, I’ve come to realize that, especially in our current context, Singer’s significance arises from his unwavering commitment to facts and arguments. Despite decades of attempts to “cancel” him (an audience member once leapt on stage, ripped off his glasses and smashed them with his foot), Singer refuses to bend to the temptation to use raw power to marginalize those with whom he disagrees.

His approach is the only way out of our current mess of a public discourse. Indeed, as far as I can tell, it is the only way to give the vulnerable and marginalized a shot at having their point of view taken seriously by those who hold power over them.