CHICAGO (RNS) — President Donald Trump and independent presidential candidate Mark Charles agree on at least one thing.

When Trump declared November for the first time to be National American History and Founders Month, Charles said the president’s call to remember history is a great idea.

Charles, a Navajo speaker and author, thinks the president should start by reading Charles’ new book, co-written with North Park University professor Soong-Chan Rah, “Unsettling Truths: The Ongoing, Dehumanizing Legacy of the Doctrine of Discovery.”

RELATED: Presidential candidate and former pastor Mark Charles confronts American history

“We are trying to create this common memory that President Trump is advocating for. The challenge is he believes in the mythology of American history, not what the actual history is. This is where we’ll diverge immediately,” Charles said.

“But to call for November to be a month to remember our founders and remember our history, my response is: That’s a great idea, Mr. President. Here is a book that I would like you to begin the process with. I will even sign it for you.”

That the president has declared the new monthlong observance alongside what has for decades been recognized as Native American Heritage Month shows how badly Americans need a “more robust history,” Rah added.

Not understanding the significance of Native Americans in that history and what the founding of the United States has meant for them “allows for this ignorance around this topic to such an extent that you would actually even consider putting these two things alongside each other,” he said.

RELATED: Denominations repent for Native American land grabs

In “Unsettling Truths,” Charles and Rah reach back to the 15th century to explain that history — starting with the Doctrine of Discovery, a series of edicts that gave Christian explorers the right to claim lands they “discovered.”

The authors hope it will help create a more honest starting point for a national dialogue to move Americans toward conciliation, Charles said.

Christians need to be part of that conversation, according to the former pastor, “because the church is absolutely complicit in creating the destructive institutions that perpetuated this history.”

The two men launched the book earlier this month at an event at Wilson Abbey in Chicago and talked to Religion News Service afterward about the Doctrine of Discovery, its ongoing impact on the U.S. and why Christians especially need to engage in truth-telling about it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

For readers who are just being introduced to it, what is the Doctrine of Discovery?

Mark Charles: The Doctrine of Discovery is a series of papal bulls written between 1452 and 1493. It’s essentially the church in Europe saying to the nations of Europe, “Wherever you go, whatever lands you find not ruled by white, European, Christian rulers, those people are less than human and the land is yours to take.” So this is the doctrine that allowed European nations to go into Africa, colonize the continent and enslave the people. It’s the same doctrine that let Columbus “discover” America because you can’t discover land that’s already inhabited. It’s called stealing. The fact that we call what Columbus did “discovery” reveals the influence of this doctrine, which is the bias that the inhabitants of Turtle Island are less than human.

Soong-Chan Rah: One of the questions we’re grappling with in the book is not only what is the Doctrine of Discovery, (it’s) what is the real, significant, historical impact of the Doctrine of Discovery? A product of European Christianity ultimately ended up shaping the modern world and has a profound negative impact, especially in communities of color.

Can you talk more about what its impact is today?

Mark Charles: First, you have to see how it influences our foundation. Our Declaration of Independence begins with the words, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” and then 30 lines later refers to Natives as “merciless Indian Savages.” The Constitution begins with the words, “We the people,” and then Article 1, Section 2, where it is determining who is and who is not a part of the union, never mentions women specifically, excludes Natives, counts Africans as three-fifths of a person.

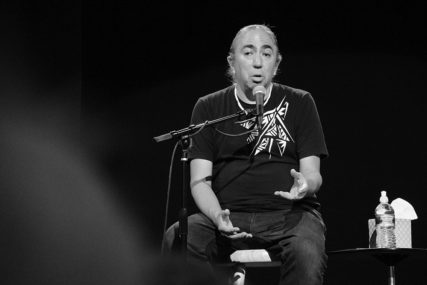

Mark Charles discusses his new book, “Unsettling Truths: The Ongoing, Dehumanizing Legacy of the Doctrine of Discovery,” during a launch event at Wilson Abbey in Chicago on Nov. 4, 2019. RNS photo by Emily McFarlan Miller

Now the other place where we see this very, very clearly is in the issue that’s very prevalent all throughout Indian Country, which is the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls, where literally hundreds, if not thousands, of indigenous women have gone missing, have been murdered, and society has responded with a collective shrug. There’s no comprehensive database. Even identifying a lot of these women, there’s been no follow-up by law enforcement. There’s been very little movement on their cases. And they’re just gone.

And so there’s a movement in Indian Country to highlight the missing and murdered indigenous women and girls. Many politicians are saying: “Well, we need to have a new law. We need to have new policies to protect more vulnerable demographics.” But when your Declaration of Independence refers to Natives as “savages,” and when your Constitution never mentions women, nobody should be surprised when your indigenous women go missing or murdered and society does not care. It’s not that we need a new law, it’s that we need a new basis for our laws.

You’ve described this book as a ‘flat-out rebuke.’ Who or what is it rebuking?

Mark Charles: The book is a rebuke to the church and a rebuke to the way the church has basically been in collaboration with empire and has been a part of working alongside empire, not speaking prophetically to it. But the book is also a call to the nation to create this common memory.

Soong-Chan Rah: The book should be seen as having two specific ways of impact: One would be as a tool for deconstruction, which is to kind of rework and rethink through history — particularly ecclesial history, the history of the church and the role of the church in American society. That’s what Mark is alluding to as a rebuke to the church: This is part of the need to deconstruct the way we’ve learned history, the way we’ve done theology, the way we’ve silenced voices.

In terms of going forward, this is where I think Mark and I are emphasizing need for common memory, the need for conversation, the need for a path forward that draws from learning from history, learning from the mistakes of the church in the past, a justifiable and necessary rebuke at this moment. How do we deconstruct the history, but then, how can we construct going forward a common memory? How do we construct movement toward conciliation?

Mark Charles: The book is really us putting forward a way to frame a dialogue so that we can begin constructing this common memory on a more national level. While it was published through a Christian publisher, InterVarsity Press, and while both Soong-Chan and I are Christians, the book was written really with a broader national audience in mind. When I speak to non-Christian audiences, I still go into this history in those lectures and in those presentations, because I tell them, if you don’t understand the history of the church, you will never understand the history of the nation. And so this book is really about trying to allow the nation to understand some of the theological grounding that has gone into the challenges that we’re facing today.

The book is written for a broader audience, but why is this topic so important for Christians in particular to engage?

Soong-Chan Rah: On a practical level, I just really believe that Christians need to be in places of learning and especially learning in areas where there’s some significant deficiency. Some of these social issues such as racism, such as the disappearance of Native women — these are very important social issues oftentimes the church is very silent on. Understanding why that is the case and understanding what are the factors that have led to where the church is now is important because otherwise you do get some folks who are saying, “Well, the church doesn’t speak on these issues because we’re silenced. We’re not allowed to talk, and we’re being persecuted for our faith.” Actually, the church has been used to persecute and to harm rather than to be the object of persecution, especially throughout American history.

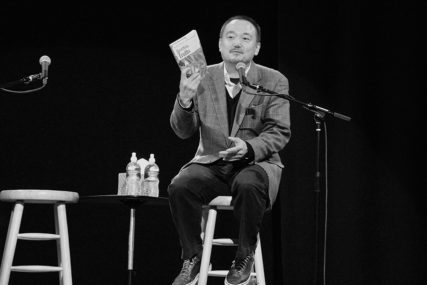

Soong-Chan Rah discusses his new book, “Unsettling Truths: The Ongoing, Dehumanizing Legacy of the Doctrine of Discovery,” during a launch event at Wilson Abbey in Chicago on Nov. 4, 2019. RNS photo by Emily McFarlan Miller

That’s where understanding these realities, understanding these truths is a necessary step for the church before it jumps in with all the answers, jumps in with trying to fix everything, jumps in saying, “We’re the answer to the problems of the world.” Let’s look at the way that we have failed. A lot of that has to do with a necessary intellectual curiosity or a necessary wanting to learn that oftentimes the church has exhibited the opposite — kind of an ignorance. That’s where it would be beneficial for the church to have some of this necessary knowledge before we speak and claim to be experts and claim to have the answers for society. Let’s actually do a little deeper thought and do a little deeper research into this before we start speaking.

Mark Charles: One of the things that I really like about the book and that I’m very excited about is it helps people to understand where the church went wrong and where the church basically left the teachings of Jesus and began to embrace this heresy known as Christendom or Christian empire. What most people today would call Western Christianity, most of the indigenous population — my people, other Indian nations and peoples around the world — would say, “Well, that’s actually not Christ. That’s empire. That’s Christendom.” And this book helps people to see one of the primary points of divergence where the church made a choice to reject the teachings of Christ and embrace the comfort and security of empire.

Now here we are 2,000 years later.

One of the questions we wrestle with in the book is how does the church get from the teachings of Jesus — who says things like “Love your neighbor” and “Pray for those who persecute you” — to writing a Doctrine of Discovery that basically says, “Kill people who don’t look, act or believe like you.” I mean, you have to do a lot of a lot of theological gymnastics to get to that point, and we help people understand how we get there. By doing this, by stripping away and identifying some of this heretical teaching, what we’re able to do is actually put the focus back on Christ.

You started working together on this book because you realized you both were writing separately on the same topic: lament. What role does lament play in response to the Doctrine of Discovery?

Soong-Chan Rah: There are all these subgenres within lament, and the precursor to lament is truth-telling. In my work on the (biblical) Book of Lamentations, one of the most powerful things about that book — kind of a sustained lament for five chapters — is that you see truth told repeatedly. Nobody’s sugarcoating the reality of what’s going on. Nobody’s making excuses for why this death and destruction occurred.

I think it’s good that more and more people are using the language of lament around social problems and challenges to the church — you know, “We lament the decline of Christianity in the West,” “We lament the death of another black body at the hands of law enforcement.” But a significant part of that lament, what I hope this book offers a step toward, is you’ve got to speak truth when you lament. You’ve got to have a reality check. Otherwise, it’s not lament, it’s just complaining.