(RNS) — Jean Vanier did not make a life focused on his own power. Quite the opposite, in fact. He made a life focused on the power of those with intellectual disabilities. A power that could change those of us who are “normal” into better examples of Christ’s love.

Vanier’s New York Times obituary last year referred to him as a “savior to people on the margins,” but that actually gets his views deeply wrong, if not completely backward. The governing philosophy of the organization he founded, L’Arche, was that able-bodied people who assisted those with intellectual disabilities should consider themselves the students of those they were serving. It was a mutual relationship, no doubt, but the power Vanier and L’Arche focused on was the power of the marginalized to change those who met them in a powerful moment of encounter.

It is hard to imagine a better antidote to the poison of our use and throwaway culture. As a result of his work, many people who knew and encountered him considered Jean Vanier a living saint.

The recent revelations that from 1970 to 2005 Vanier had manipulated and sexually abused at least six women in the context of “spiritual accompaniment” are as shocking as they are devastating.

Our first instinct must be to think about the six brave and powerful women who came forward to share their stories. Thank God they were able to air their pain and suffering this man caused them over decades.

But there are other victims to think about as well. Soon after the news broke, Catholic News Agency’s J.D. Flynn tweeted that it was particularly painful for his family, not least because one of his children is named for Jean Vanier. The Rev. James Martin described the news as a “grave disappointment.” Colleen Dulle wrote that she, like so many, could not even really process this news.

If Jean Vanier is not good — indeed, far from it — who can be good?

Here it is important to remind ourselves of Jesus’ humbling claim that “no one is good but God alone.” We are fallen, broken, depraved creatures in desperate need of God’s mercy and grace. We must let that disturbing reality sink in. Profound sin lurks even within the best of us. Sometimes, as in this case, even horrible sin lurks within the best of us.

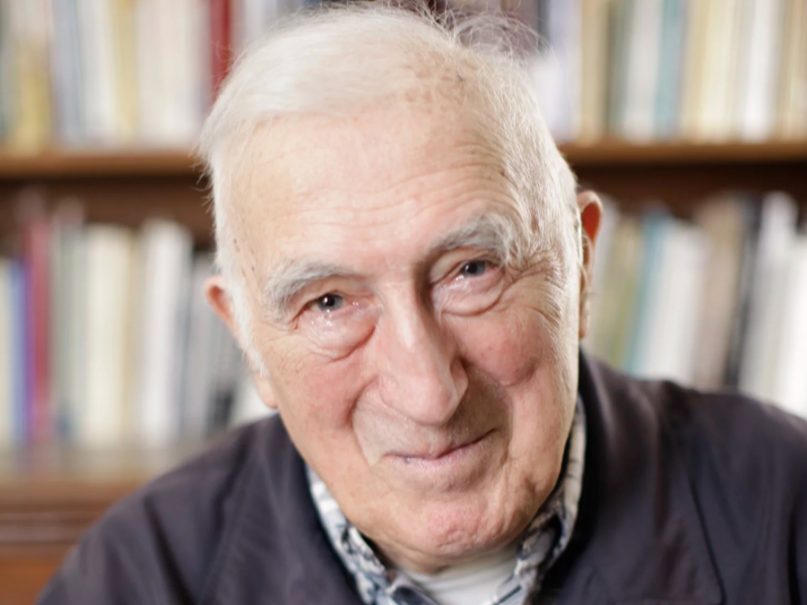

Jean Vanier visits Sebastien, a young man whose injuries in a car accident left him with profound cognitive and physical disabilities, at the L’Arche care home in Trosly-Breuil, France, in 2015. Photo courtesy of Summer in the Forest/R2W Films

But there are other lessons to take from the Vanier revelations. One is that we should return to older processes by which someone becomes a saint — bringing back the devil’s advocate — and take our long, sweet, Catholic time in attempting to decipher God’s will in such matters. Another lesson is that the corrupting power of sinful sexual context can turn even the best people into the worst. Vanier’s views about sex were formed in the context created by his spiritual mentor, the Rev. Thomas Philippe, who abused a number of women in ways that were strikingly similar to Vanier’s.

Who or what is forming our current cultural view of sex? Well, due in no small part to the smartphone, the average child first experiences hardcore porn at age 11. Degrading, violent, disgusting and very often illegal digital porn clips are now easily the most powerful force at the center of forming what our culture thinks about what sex is for.

For decades now I’ve heard criticism, often coming from older people on the left, that their perceived opponents on the right are too focused on “pelvic issues.” But in our post-#MeToo movement, it appears that pelvic issues are a focus across the political spectrum. This is no less true with younger people on the political left, who tend to point out that sexuality comprises some of the deepest parts of who we are as human beings, and that the vulnerabilities that go with sexual relationships open us to the deepest kinds of wounds.

In our debates over sex, St. Augustine often gets thrown under the bus as the figure primarily responsible for negative attitudes toward sex. Augustine’s critics would have it that his influence pushed later generations in the West to deny that sexual pleasure can be a part of a flourishing relationship based on other-centered love.

There is some truth to this, but, as University of Notre Dame theologian John Cavadini demonstrates, it’s a real question whether in Augustine’s day sexual pleasure was possible without the distinct moral taint of violence and self-centered lust. The most powerful institutions of the time had thoroughly baked those concepts into their understanding of what sex was.

It’s difficult not to notice that our cultural context has important overlaps with Augustine’s. Is it possible for a sexual culture formed by Pornhub to avoid his critique?

Augustine had firsthand experience with the special corrupting power of sexual sin. In a countercultural move, he tried to warn the people of his day of this fact — and this warning has much to say to us as well.

When this power can corrupt even someone like Jean Vanier, it should be clear that we are clearly facing a special power of the Evil One. It is time, without hesitation or embarrassment, for millions across the political spectrum to return to a focus on resisting the corrupting power of sexual sin.