(RNS) — This Passover, my family will be doing what Jews all over the world are doing — gathering for seders on Zoom.

No more getting the kids home. No more opening the dining room table and organizing who’s bringing what to eat.

We will cobble together our meals at our own small tables and proceed through the Haggadah as best we can. When we lift up the ritual matzahs and say, “Let all who are hungry come and eat; all who are needy come and celebrate Passover with us,” we won’t mean it, not if it involves actually inviting someone into the house. Not happening.

The only guest we’ll be opening the door for is the prophet Elijah, and depending on where we live, maybe it would be better to invite him ([email protected]) to show up virtually himself. Either way, we’ll set out his cup of wine and sing, “May he swiftly in our days come to us, with the Messiah son of David.”

Elijah’s principal claim to fame in the Bible is as the spiritual adversary of the evil king of Israel Ahab and his even more evil pagan wife, Jezebel. After defeating 950 of Jezebel’s prophets in a competition to get their respective god to consume a sacrificed bullock, Elijah has the people slaughter them.

His claim to companionship with the Messiah rests on the end of his life on Earth, when in 2 Kings he’s assumed into heaven in a whirlwind; and through the prophecy at the end of Malachi: “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the great and terrible day of the Lord. And he shall turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers; lest I come and smite the land with utter destruction.”

Tales about Elijah abound in Jewish folklore. My favorite concerns the third-century rabbi Joshua ben Levi who, in the Babylonian Talmud, meets Elijah at the tomb of the sage Shimon bar Yochai and asks when the Messiah will come. “Go and ask him yourself,” replies the prophet.

“Where is he?”

“At the gates of Rome.”

The Messiah, it seems, is spending his time helping the diseased Jews there, who re-bandage their sores once a day. The Messiah is ministering to just one person at a time, in case he is called to his mission.

So Joshua goes to Rome and finds him. “Peace unto you, Master and Teacher,” he says. “Peace unto you, son of Levi,” replies the Messiah.

“When will you come, Master?”

“Today.”

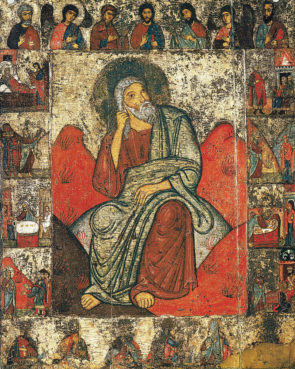

Russian icon of the Prophet Elijah. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

When Joshua returns from his journey, Elijah asks him what the Messiah said. “Peace unto you, son of Levi.”

That means, says the prophet, that he was assuring both your father and you a portion in the world to come. “He lied,” responds Joshua, “saying he would come today, but he hasn’t.” And Elijah answers, “What he was saying to you is that he’ll come today, if you will hear his voice.”

Did Joshua hear his voice or not?

The great scholar of Jewish mysticism, Gershom Sholem, saw this story as a “truly staggering” example of the Jews’ belief in the “occultation of the Messiah” — their touching conviction that the agent of their communal redemption was hidden but always at hand, ready to spring into action at a moment’s notice.

It is a belief, he writes, that has taken many forms, “though admittedly none more grand than that which, with extravagant anticipation, has transplanted the Messiah to the gates of Rome, where he dwells among the lepers and beggars of the Eternal City.”

At this time of global pandemic, when we’re left wandering in cyberspace to celebrate our redemption from Egypt, the occultation of the Messiah is certainly to the point. And so is the image of him ministering to the sick and the image of Elijah always at hand to provide some measure of assurance.

And, come to think of it, the silver lining on this beclouded Passover is that we rank-and-file members of the tribe get to be a little like Elijah ourselves. My immediate family will not only be coming together for our own seders, but, thanks to Zoom, we’ll be dropping in on a few others as well. That will be an experience to remember, if not one we’re anxious to repeat.

According to the Haggadah, a seder officially ends with the words, L’Shanah Haba’ah b’Yerushalayim: “Next year in Jerusalem!” This year, I propose we content ourselves with L’Shanah Haba’ah ishit: “Next year in person!”