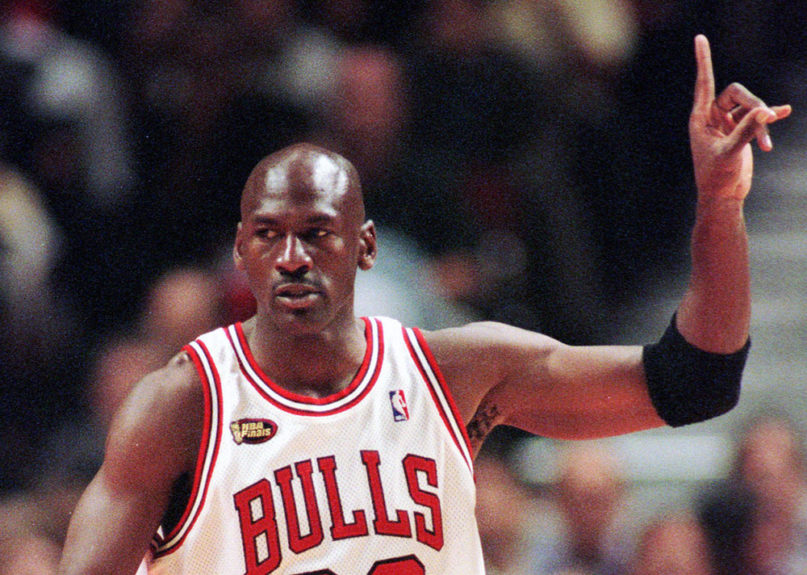

(RNS) — I’m not at all unbiased when it comes to Michael Jordan.

I grew up on the Wisconsin side of the Cheesehead vs. Chicago sports culture wars. I also ended up an intense fan of Charles Barkley — perhaps because we shared a first name— when he played for the Philadelphia 76ers.

MJ tore my heart out so many times. In the 1990 and ’91 playoffs, he beat Barkley’s very good Sixer teams almost single-handedly. We didn’t have cable TV in rural Wisconsin back then, so I listened to Jimmy Durham and Johnny “Red” Kerr call the games on Chicago radio. Somehow it was worse having to provide the visuals in my mind’s eye as Jordan took down the teams I loved.

Two years later, after my idol had moved to the Phoenix Suns, the Jordan-led Bulls dramatically defeated the Suns on a last-second 3-pointer. That year, Barkley won the MVP and the Suns had the best record in the league (in a much-better Western Conference), and still Jordan and the Bulls prevailed and sent me into a deep summer funk.

I’m annoyed, still, by the media’s coverage of the 1992 Dream Team. Barkley was the clear MVP and star of the greatest team ever assembled — his 3-pointer, when the U.S. was down 25-23 to Croatia, was actually responsible for the total shift in momentum of the gold medal game. But Jordan still gets all the credit.

Despite my bitterness, I acknowledge Jordan’s greatness. Any fair-minded person confronted by objective evidence is forced to acknowledge it. Indeed, I was excited for a new generation of basketball fans to encounter this evidence in ESPN’s 10-episode documentary, “The Last Dance,” which spends most of its time following Jordan’s Bulls as they win six NBA titles in eight years.

While I was prepared to be reminded of MJ’s greatness, I was not prepared to be confronted with the cost at which that greatness came. Still less was I prepared for Jordan himself to be personally and emotionally confronted with that cost.

In perhaps the most poignant part of the documentary, the interviewer suggests to Jordan that his greatness and winning may have come at the expense of him being perceived as a nice guy. At that moment Jordan visibly tears up and says:

When people see this, they’re going to say, “Well, he wasn’t really a nice guy, he may have been a tyrant.” Well that’s you, because you never won anything. I wanted to win, but I wanted them to win and be a part of that as well. I don’t have to do this. I’m only doing it because it is who I am. That’s how I played the game. That was my mentality. If you don’t want to play that way, don’t play that way.

By the time he finished these words he was so overcome with emotion that he had to call for a break in the interview.

Jordan’s nastiness first came out in the book “The Jordan Rules” by Bulls beat writer Sam Smith, but the ESPN documentary makes it clear as well: Many of Jordan’s teammates lived in abject fear of what he would do to them if he became displeased.

Steve Kerr said he was “scared to death” of Jordan — which is not surprising given that Jordan once punched Kerr in the face (and was kicked out of practice for it by Bulls head coach Phil Jackson).

Will Perdue said, “He was an a–hole, he was a jerk, he crossed the line numerous times.” In “The Last Dance,” we see footage of Jordan hounding and bullying younger players like Scott Burrell.

Perhaps the person he got on the most, however, was Horace Grant. Grant has been aggressively critical of “The Last Dance,” arguing that it is more like a piece of Jordan propaganda than a truly objective, journalistic documentary.

And who can blame him? Smith revealed in “The Jordan Rules” that, among other things, MJ would refuse to let the stewards on their private flights even give Grant his meals if he felt like the Bulls forward had had a poor game.

This not only reveals the power Jordan had within the organization, but the cruelty with which he could wield such power. When confronted with these kinds of negative responses from former teammates, Jordan’s response was, “Winning has a price.”

Indeed. And as the tears welled up during that part of the interview, Jordan was evidently confronting that price. The price of becoming the greatest of all time, the GOAT, in the game of basketball.

Here one may be reminded of the wisdom of St. Paul in 1 Corinthians Chapter 13, when Paul claims that you can have everything that the world values — but if you don’t have love, you actually have nothing at all. If Michael Jordan had to give up on treating his teammates with love in order to win, then, at least from a Christian standpoint, his winning meant nothing.

Sports journalists often point to the careers of great athletes who didn’t win a championship and call their greatness into question by asking, “Where are the rings?” Christians, by contrast, must look at the careers of great athletes and ask, “Where is the love?”

Barkley famously insisted that he was not a role model. And despite Gatorade’s insistence that we “be like Mike,” we now know that Jordan was not a role model either.

The price he paid for winning was just too great.

The Bible reference from 1 Corinthians 13 has been updated in this story.