Tish Harrison Warren. Courtesy photo

(RNS) — I catch Tish Harrison Warren by phone as she is poised on the threshold of a new life. She has just arrived in Austin, Texas, where she is going to be a writer-in-residence at Resurrection Anglican Church. After three days in the car with her husband and three children (ages 10, 8 and 16 months), she is eager to walk, which she does while she chats on the phone about her blossoming career.

If all that sounds idyllic and easy, you should read her new book. “Prayer in the Night: For Those Who Work or Watch or Weep” is not a memoir, per se, but its deep theological insights are repeatedly grounded in Warren’s own experiences as a mother and an Anglican priest. And many of those experiences have not been idyllic or easy.

The book opens with an arresting scene from 2017 when Warren was gushing blood in the emergency room. In the throes of a miscarriage, the only words she could grasp to pray were those of the Compline liturgy. Somehow, this classic nighttime prayer (“Keep watch, dear Lord, with those who work, or watch, or weep this night, and give your angels charge over those who sleep … ”) gave her a foundation for trusting in God when she couldn’t quite rally her own faith.

That was not the only acutely painful experience of that year, which she chronicles in “Prayer in the Night,” organizing the book around the various phrases of Compline.

“It’s not hard for me to share my story in writing. That’s kind of the only way I know how to write,” Warren says. “I abhor abstraction.”

But the book was still difficult to create, because it meant revisiting that terrible year.

“I was like, ‘Lord, I don’t want to have to go back into all that again.’ To feel it again, to experience it. It felt like writing was walking back in, and having to sit with it and dwell on it. I had to remember and name the doubts I was having in the midst of that, and the fear and the sadness. All of that felt really hard.”

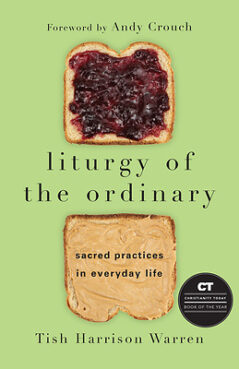

Warren’s willingness to enter that kind of vulnerability has resonated with readers, who made her first book, “Liturgy of the Ordinary: Sacred Practices in Everyday Life” (2016), a Christian best seller. Christianity Today chose it as its Book of the Year for 2018, and it received a starred review in Publishers Weekly and praise from the Chicago Tribune.

Warren’s willingness to enter that kind of vulnerability has resonated with readers, who made her first book, “Liturgy of the Ordinary: Sacred Practices in Everyday Life” (2016), a Christian best seller. Christianity Today chose it as its Book of the Year for 2018, and it received a starred review in Publishers Weekly and praise from the Chicago Tribune.

But with that success came unwanted attention in the form of counterfeiting. In 2019, Warren learned thousands of fake copies of “Liturgy of the Ordinary” had been sold through Amazon. The counterfeiters “printed it to look exactly like “Liturgy,” and when you bought it, it had all the same text. Except that there were typos in it, and some weird font differences.” Also, the cover was not rendering correctly.

Warren was not alone in being a high-profile victim of literary theft. Earlier that year, The New York Times had run an article about the growing counterfeiting problem among award winners on Amazon, including counterfeit sales of books by Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Andrew Sean Greer (“Less,” from Hachette) and National Book Award nominee Lauren Groff (“Florida,” from Riverhead/Penguin Random House).

Warren and her publisher, InterVarsity Press, still don’t know who was responsible for the counterfeiting, but she estimates that up to 20,000 counterfeit copies were likely sold that way. She had achieved what most authors only dream of — a marvelous success right out of the gate with her very first book, which she had labored over for three years — only to have her work pirated by unseen and, as yet, uncatchable thieves.

“It did feel like a violation,” she says. “I had not had anything stolen from me before. You put your heart and soul into books, especially one so personal.”

But in an optimistic twist, Warren has found at least one silver lining: Because the theft was widely reported, a German publisher heard about the controversy, and therefore learned about the book, and purchased translation rights for a German-language edition.

Despite the counterfeiting loss, Warren says she’s grateful for the tremendous response to the book, which IVP reports has sold more than 121,000 (genuine) copies to date.

She did not set out to become a professional writer and only began writing in 2013, when as an InterVarsity staff member she published a short piece for The Well that went viral. That exposure was thanks to a well-placed recommendation from evangelical Christian thought leader Andy Crouch, whom Warren now credits as a writing mentor. In the following years, she practiced her craft at outlets like her.meneutics (the now-retired women’s site of CT), RNS and The New York Times.

She also did not set out to become a priest. In fact, she grew up Southern Baptist and then joined the Presbyterian Church of America as a young adult — both denominations that did not ordain women. She was actively involved in church work, though, with a passion for social justice and working with the poor. Through this work, she decided to go to seminary because she “absolutely loved theological education” and couldn’t get enough of reading theology.

Her husband started seminary, too, and in the course of writing an exegesis paper on the famous verse from 2 Timothy about women not teaching in church or having authority over men, he became convinced that women in fact should be in positions of authority.

“That began a journey of him and I reading and arguing and studying,” she says. “The joke is that eventually I finally submitted to my husband and got ordained.”

She had by then joined the Anglican Church in North America, which not only ordained women but also focused so powerfully on liturgy and sacrament that she felt guided to choose ordination for herself.

“It became where I felt like I didn’t know how to do pastoral care anymore without the Eucharist. That’s a priestly calling in the Anglican church, because the only way you can celebrate the Eucharist or take confessions is as a priest. So I felt like that’s what I was called to do.” In 2012, at age 32, she became an Anglican deacon and then a priest in 2014.

The focus on liturgy is the scaffolding that undergirds “Prayer in the Night.” When I ask Warren to name some of the authors who have most influenced her, there is a strong tilt toward Catholic and Anglican thinkers: Dorothy Day, C. S. Lewis, Flannery O’Connor, Madeleine L’Engle, Michael Ramsey and Gerard Manley Hopkins are all on the list. She even named her son after Saint Augustine.

The Anabaptist tradition has also shaped her thinking. “I probably ended up Anglican because I’m kind of an Anabaptist Catholic,” she says, noting that ethicist Stanley Hauerwas has been a “huge influence.”

“Prayer in the Night” is shot through with deep theological insights, but the writing is so personal and down to earth that it’s primed to find an audience of readers who wouldn’t go out of their way to dig through theology.

“There’s a theme of prayer and received prayer that I hope will help some folks. And there’s a theme of mortality and vulnerability,” she says. “I would love this to give people permission to really look at the grief in their life, and the struggle to believe, and be able to meet God in those questions and those places of grief.”

A sampling of Tish Harrison Warren’s writing for RNS:

Willow Creek’s crash shows why denominations still matter (2019)

In my church, some of us voted for President Trump. All of us pray for him. (2019)