“So, Rabbi, last week you wrote about whether Jews believe in angels.

“What about saints?”

Good question.

The general definition of a saint is of someone who is exceptionally holy or close to God. In Christianity, formal recognition of sainthood requires canonization, and the attestation to the performance of miracles. Sainthood has sometimes involved the worship of relics; pilgrimage to various sites associated with the life of the saint; and the belief that the saint can intercede with God.

In Judaism and Christianity, it is somewhat different. There is no ecclesiastical body that makes a formal declaration of sainthood. Miracles are, at best, problematic. So, too, are relics — though sometimes Jews will make miniature “pilgrimages” to burial places of various tzaddikim and tzaddikot (righteous women). In that sense, informal, folk sainthood exists across all three of the Abrahamic faiths — Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

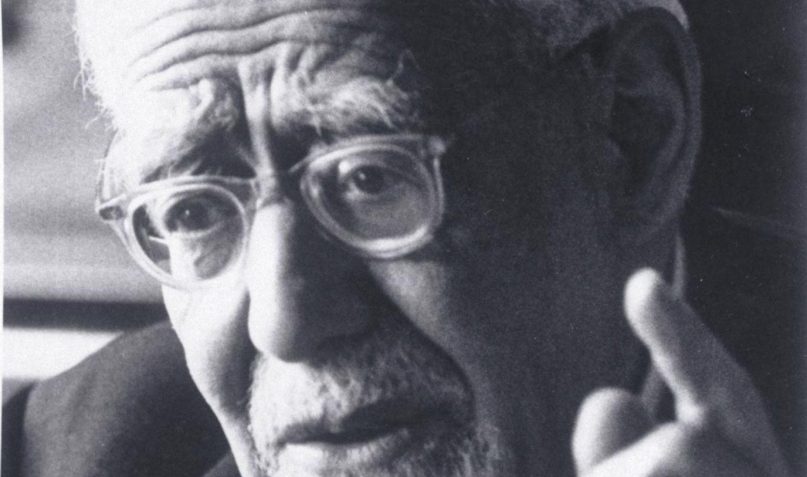

That being said: if they were about to take nominations for Jewish saints, I would stand up and shout the following name: Rabbi Leo Baeck.

I had known the story of Rabbi Baeck for decades. I had read about him. But nothing could have prepared me for this majestic, magisterial new biography of him by my friend and teacher, Michael Meyer — Rabbi Leo Baeck: Living a Religious Imperative in Troubled Times.

I simply could not put down this story of the great German progressive/Reform/liberal rabbi, who rose in his career until he became the (almost) undisputed leader of German Jewry during the most challenging and painful years of its history — the 1920s, and heading into the Shoah.

We recognize and can relate to Baeck’s Jews — those German Jews who were “adherents of a lazy Liberal Judaism that was peripheral to most of their lives;” who silently uttered to their German countrymen “Please pardon me for existing;” who built awe-inspiring, architecturally notable cathedrals — that were relatively empty except for the High Holy Days.

The Baeck biography becomes particularly heartbreaking when the darkness descends on Germany Jewry, especially with Kristallnacht. Professor Meyer reminded me that after that huge pogrom, none other than Mahatma Gandhi suggested that the German Jews should engage in mass suicide, on a single day at a single hour, as a spectacular collective act of protest; then would the European conscience awaken.

Outrageous. Obscene, even.

Baeck kept his cool, and reminded the Mahatma that Judaism was intoxicated with life.

And then, Baeck was deported to Theresienstadt, the so-called model concentration camp for the central European Jewish elite. When the Gestapo appeared at his home to arrest him, the rabbi refused to go until he had paid his gas and electric bills. Once at Theresienstadt, the 69 year old rabbi was forced to pull hearses, used as carts to carry bread and potatoes. He discussed philosophy with another man who was harnessed at his side.

Meyer paints a disquieting picture of Theresienstadt. True — it became a cultural center, which was part of the Nazis’ ruse. We know of the children’s theater, the art workshops, the musicals. The most talented people in Europe were interned there.

And yet, Meyer refuses to romanticize the camp. He writes of the power plays among leadership, the corruption — and yes, the sexual excesses that happened in the camp.

As one survivor put it, “Morals went to hell here.” She told of a youth club that admitted young women only after they had slept with all its male members. Another told of what was happening in younger families: following the evening meal, “each went his own way, the wife to her lover—frequently, someone else’s husband—the husband to his mistress.” As Zdenek Lederer understood the scene: “Only the present was real, and the best way to fight its depressing effects was by the pursuit of pleasure, in particular sexual pleasure.”

The largest moral issue that emerges from Meyer’s book — and that is the debate over whether Baeck was right to have kept his knowledge of the ultimate fate of the Jews to himself. His reasoning was clear. There was already a pandemic of suicide among German Jews. He refused to do anything that would increase despair, and thus amputate hope.

Bear in mind, as Meyer reminds us: during this period, it was not the practice of physicians to tell terminally-ill patients of their ultimate fate — again, so as not to amputate hope.

Was Baeck right in keeping these ghastly truths to himself?

Balance that question with the following realization. Baeck was in the position to save his own loved ones from death. He categorically refused to do so.

As a result, a niece and nephew boarded a transport headed for a death camp. Other relatives died in the ghetto or were sent directly to the East. Baeck lost four of his sisters in Theresienstadt, three of them before he arrived, and the fourth shortly after his arrival. Both his brothers perished in a death camp. These personal losses were among the painful memories that underlay Baeck’s reluctance in later years to recall his ghetto experience.

Michael Meyer is correct when he says that Leo Baeck’s theological writings do not enjoy the same academic scrutiny as those of his landsmen Hermann Cohen, Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig — nor of his student, Abraham Joshua Heschel.

And yet, no other personage in non-Orthodoxy – or at the very least, Reform Judaism—has as many institutions that bear his name.

- In Israel, the Leo Baeck School in Haifa, founded by Baeck’s colleague Max Elk

- In London, the Leo Baeck College, a rabbinical seminary for the British Liberal and Reform movements, and also a Leo Baeck Fellowship

- In Los Angeles, Leo Baeck Templ, whose senior rabbi is my friend, Rabbi Ken Chasen.

- In Canada, Leo Baeck Day School in Toronto

- In Germany, the Leo Baeck Foundation supporting Liberal Judaism, Leo Baeck Street in the Zehlendorf section of Berlin, and the Leo Baeck Prize, the highest award given by the Central Association of Jews in Germany

- In New York, Jerusalem, London, and Germany—the Leo Baeck Institute, dedicated to the preservation and critical study of the German Jewish legacy.

His legacy survived, as well, in his grandson-in-law, the late Rabbi A. Stanley Dreyfus, whose son married Rabbi Ellen Weinberg Dreyfus.

Finally, my favorite Leo Baeck story.

Apparently, a certain Rabbi Beck died, and in April, 1945, when Adolph Eichmann was at Theresienstadt, he encountered Leo Baeck. Baeck recalled:

Eichmann was visibly taken aback at seeing me. “Herr Baeck, are you still alive?” He looked me over carefully, as if he did not trust his eyes, and added coldly, “I thought you were dead.”

“Herr Eichmann, you are apparently announcing a future occurrence.”

“I understand now. A man who is claimed dead lives longer!”

Was Rabbi Baeck a “saint?” Yes — in the same way that many other inspirational religious figures have embodied that sense of self-transcendence. We might even echo Eichmann — that a people that was claimed dead has lived longer.

We need this biography of Leo Baeck. Why? Because as we emerge from the depths of the pandemic, and as we think about all the “life hacks” that we have had to do in order to perpetuate our synagogues and institutions — Zoom services and classes, etc — I find myself saying that if Leo Baeck could do his “job,” and elegantly so, in Theresienstadt, so could we.

We did, didn’t we?

In just such a way, the spirit of this tzaddik has lived longer than he himself might have imagined.