(RNS) — As a progressive and a Mormon, I’ve grown as used to struggling with some of the church’s policies as I am with avoiding cappuccinos and cosmopolitans. When it was founded nearly 200 years ago, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was revolutionary in calling for abolishing prisons — which is still on many progressives’ agendas. But you won’t learn that in an LDS Sunday school class today.

So it is with equal parts confusion and relief that I have lately found myself agreeing with the leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Speaking virtually last fall to students at Brigham Young University, Dallin Oaks, the man next in line for president of the church, declared, “Black lives matter is an eternal truth all reasonable people should support.” He followed this in April with a worldwide address condemning the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection (albeit without naming the event). In December, apostle Dale Renlund issued a video calling mask-wearing “a sign of Christ-like love.”

Still, nothing has set my bleeding liberal heart beating faster than the church’s quietly growing efforts to support immigrants living in the United States.

Latter-day Saints are the most reliably Republican of any religious group in the nation, whereas the GOP is increasingly defined by its hostility toward not just immigration, but immigrants. In June alone, three Republican governors announced their states were sending reinforcements to Texas to guard against what right-wing media has framed as an out-of-control influx of dangerous, democracy-destroying foreigners.

The same month, the church issued a press release that began: “When Dan and Lorrie Curriden look at the faces of the immigrants they serve in Las Vegas, they see the courage of their own immigrant grandparents.”

The Curridens, it turns out, are just two of a growing fleet of volunteers operating more than a dozen LDS-led, locally run “welcome centers” for immigrants coming into the U.S. These centers have taken root in cities from Mesa, Arizona, to Chicago. While each is tailored to its community’s needs, all of them share the goal of helping newcomers learn English and navigate life in the United States — including helping them access government resources.

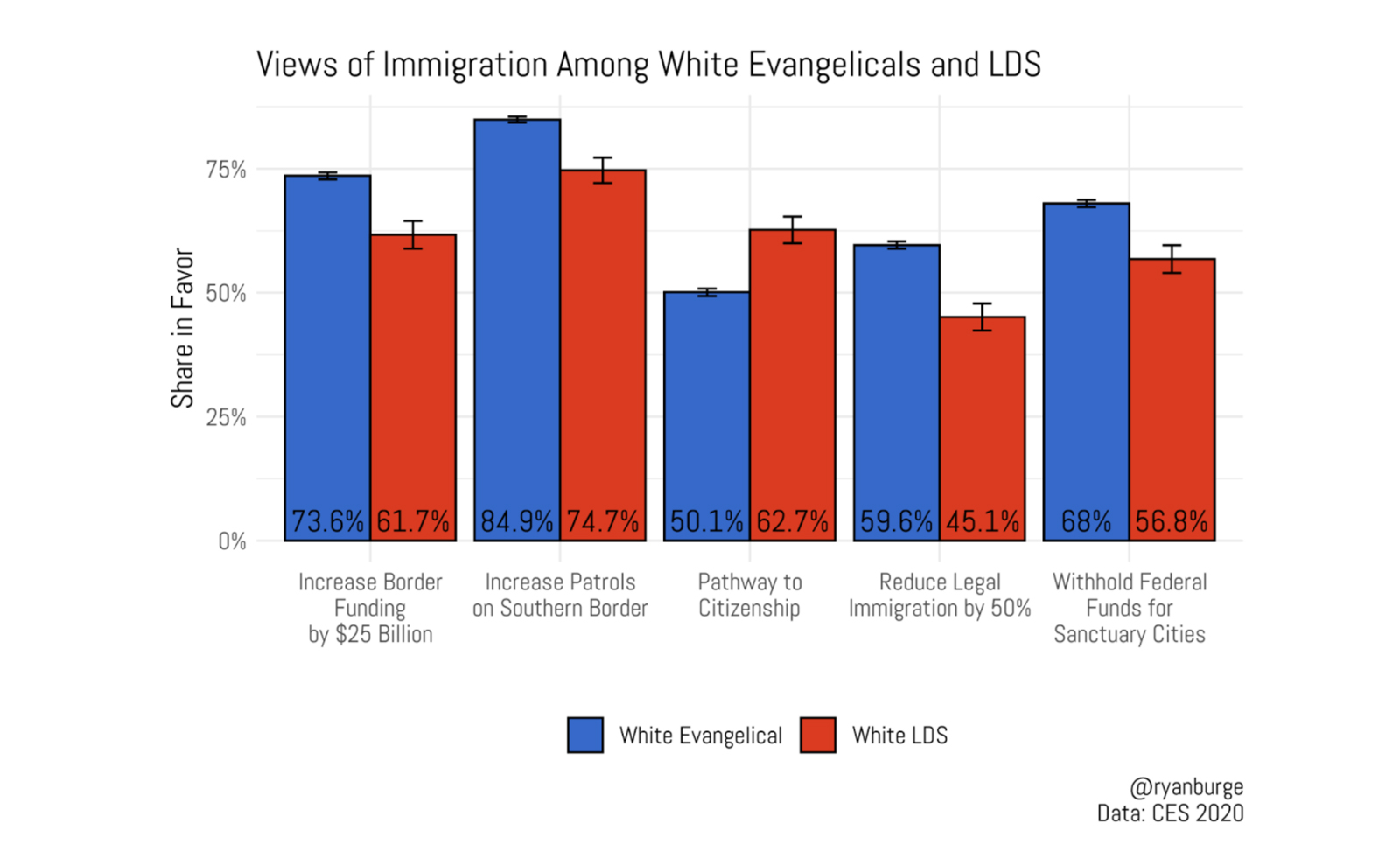

This outreach doesn’t come out of nowhere. For years church leaders have advocated for compassionate immigration policies that focus on keeping families together. Research, as the graphic below shows, indicates that Latter-day Saints tend to be softer on immigration compared with their white evangelical peers.

But as BYU’s Quin Monson was quick to point out, church leaders remained largely quiet on the issue throughout much of the Trump presidency. “I would have expected a more forceful statement about the child separation that was occurring,” the political scientist said.

“Views of Immigration Among White Evangelicals and LDS.” Graphic by Ryan Burge

Graphic created and provided by Ryan Burge, assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University. Data source: Cooperative Election Survey

Cynically, I wondered if these centers were another way of funneling potential new members through LDS houses of worship: “Here are a few English lessons, and on your right the font where we baptize people.”

Or perhaps they were largely geared at supporting immigrants who were already members of the fold.

Lorrie Curriden said neither is true. She estimated that 90% of the individuals that come to the Las Vegas location where she and her husband volunteer are non-LDS. As for proselytizing, she was emphatic: “Our purpose is to help people with their temporal needs, following the example of the good Samaritan, not an attempt to get people to come in so we can hand out copies of the Book of Mormon.”

Overall support for these centers appears to be high. According to Lorrie, the Las Vegas area alone is on track to add three more in the next few months. Powering this neck-snapping growth is an enthusiasm that, she said, extends all the way to the church’s top brass. “Salt Lake has absolutely been supportive,” she said.

Neither are these centers the only form of outreach taking place. In the part of Los Angeles County where I live, there has been a significant push among Mormons to collect and organize donations for unaccompanied minors awaiting reunification with their families.

I’m thrilled by this. The more distance between the church and the GOP the better, as far as I’m concerned. But where does that leave the overwhelming majority of America’s Mormons?

David Campbell is a political scientist who teaches at the University of Notre Dame and is co-author, along with Monson and University of Akron political scientist John C. Green, of the 2014 book “Seeking the Promised Land: Mormons and American Politics.” Campbell predicts that, for Latter-day Saints who hold the GOP’s “hard-line” view on immigration, the next few years are going to see their political and religious identities collide.

“Immigration as an issue is going to reach a boiling point within Mormonism,” Campbell said. “I think that’s inevitable.”

How many fall into this group of immigration hard-liners is unclear. Campbell suggested a plurality; Monson estimated they represented about a third of Mormons who call themselves Republican. The other two-thirds, the latter said, are far more invested in what their religious leaders have to say on an issue than their party leaders.

RELATED: Younger US Mormons voted for Biden, but Trump performed well overall

“When the church speaks out, they take notice,” he said.

Hearing this gave me hope, and not only for the possible humanitarian implications of a (mostly) united LDS membership behind supporting our nation’s newcomers. In a world where wearing a mask during a pandemic is political, shared views on welcoming the stranger would represent a much-needed demilitarized zone between the rest of us.

Tamarra Kemsley. Courtesy photo

Lorrie has already seen this at work. “I have to say it’s kind of beautiful to see my very conservative relatives to my very progressive relatives be equally excited about the assignment and about the opportunity we have to love and lift people.”

(Tamarra Kemsley writes on the intersection of faith and politics. Follow her on Twitter at @tamarranicole. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)