(RNS) — Jews are proud of the biblical story from Exodus that recounts their deliverance from slavery in Egypt in the third century B.C.

But few U.S. Jews consider that some of their ancestors were slaves in the trans-Atlantic slave trade that ended in the 19th century.

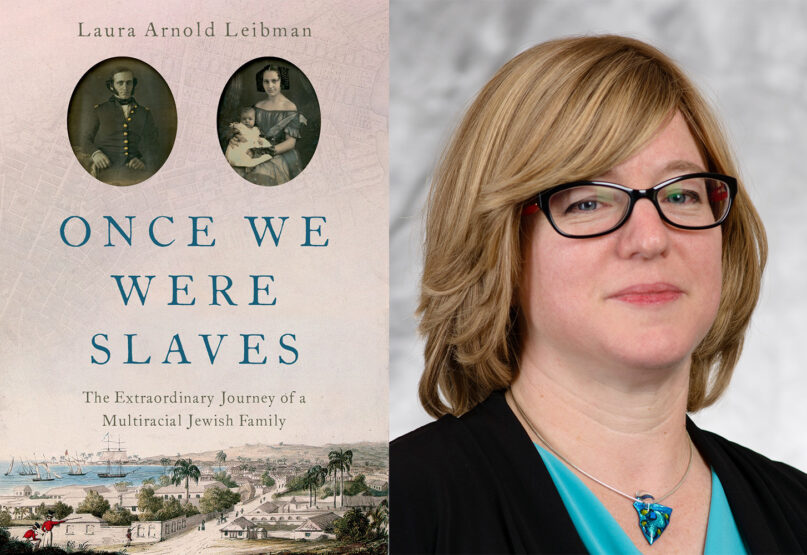

In her new book, “Once We Were Slaves: The Extraordinary Journey of a Multiracial Jewish Family,” Laura Arnold Leibman, a Reed College English professor, conclusively shows that Jews, who were typically thought of as white, were not only slave owners. They were also slaves.

Leibman does this by excavating the genealogies of Sarah and Isaac Lopez Brandon, siblings born in the late 18th century to a wealthy Barbadian Jewish businessman and an enslaved woman. The siblings eventually made it New York, where they were able to pass as white. They became accomplished and affluent members of New York City’s oldest Jewish congregation, Shearith Israel.

Sarah and Isaac’s father, Abraham Rodriguez Brandon, was a Sephardic Jew who traced his ancestry to the expulsion of Jews from Spain. He settled in Barbados as part of a Jewish community of between 400 and 500 families that worked on the island’s sugar plantations and refineries.

Brandon secured his children’s manumission fees, and in 1801 they became “free mulattos.” In Barbados, that still meant they could not vote or hold office, or for that matter be married in the island’s synagogue or buried in its cemetery.

RELATED: He claimed white Jews gained from white supremacy. Now he’s more popular than ever.

But America was kinder to them. Both Sarah and Isaac immigrated to America and married into prominent and wealthy U.S. Jewish families while hiding their past. One granddaughter had no clue about their origins.

Religion News Service talked to Leibman about her discovery of the Brandon genealogy and what it means for the U.S. Jewish community to grapple with its multiracial past and present. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

How did you trip on this amazing story?

Many years ago, when I was working on a different book, I interviewed Karl Watson, an expert on the Jews of Barbados. He mentioned an incident in the synagogue minutes about Isaac Lopez Brandon and his fight for civil rights and how he had eventually been cast out of the synagogue. I stored it away. Years later I was entranced with Isaac Lopez Brandon. I started working with a student on what was going on with the battle for civil rights and how it intersected with people of color on the island. It wasn’t until many years later that I was able to prove that Sarah, who was manumitted with him, was the same sister who lived in New York.

How many slaves integrated into Jewish households and became Jewish?

There are a lot of people who lived at the margins of the Jewish community because they were genealogically related to Jews or are in households where they pick up Jewish religious practices. But because conversion was so rare in early Barbados, they often hover at the edges of the Jewish community until they’re able to join openly later.

Why was the Jewish community so opposed to converting them?

My guess is it was politics on the island. They experienced antisemitism and pressures not to do so. Barbadian Jews didn’t want to push against Anglican elites and jeopardize their own standing. They’re not converting anybody at that period, not just people with African ancestry.

Were Jews more likely to take up with slaves in Barbados?

No. The reason why you see such a large percentage of people who have one foot in the community of free people of color and one foot in the Jewish community is that there’s a large proportion of Jews and people of color. They’re living right next to each other.

Portrait of Sarah Brandon, ca. 1815–16. Watercolor on ivory. Image courtesy of American Jewish Historical Society

We see that in the story of Sarah and Isaac. Their mother’s father is Anglican. Their father is Jewish. Their mother is enslaved by Jews. She meets Abraham Rodriguez Brandon. They never officially marry. But by the time her children move to New York she takes his name and is accepted by the Jewish community in New York and Philadelphia. She and her mother and grandmother are referred to as multiracial in the records.

In Barbados, freed slaves often owned slaves. How did that happen?

In Bridgetown, the vast majority of people who were once enslaved and later owned their relatives did so because it was too expensive to free them. So it’s a way of being able to protect the relatives, even if they can’t pay the high fees to get them legally free. Sarah and Isaac inherit their own great-grandmother, presumably so they can take care of her. There are the very wealthy free people of color in Barbados who own large numbers of enslaved people and are running plantations. That’s not the norm. It’s much more common for people to inherit relatives from their previous owners and it’s a way of keeping them safe.

The early synagogues were very different from today. They were benevolent societies that took care of people into their old age. How did synagogues work in those days?

To receive welfare, you needed to belong to a religious organization and the one deemed appropriate for you by the powers that be. If you were born Jewish, you couldn’t get money from the Anglican church. Synagogues were quite powerful. In some synagogues, a third of the money they collected went to pay for poor Jews. Particularly for women, it was really important to be in the good graces of the synagogue board. Some synagogues put in rules about having to live in the town for a certain amount of time or rent a seat in the synagogue for a certain amount of time to become a member. They’re trying to protect the synagogue from a whole bunch of people coming in from someplace else and transforming it.

The book is the perfect example of how race is a social construction. Can doing genealogy help people understand that?

“Once We Were Slaves: The Extraordinary Journey of a Multiracial Jewish Family” by Laura Arnold Leibman. Courtesy image

Yes and no. Genealogy tests will tell you you’re this percent Jewish and this percent that — like it’s embedded in you. That’s exactly what we don’t want to emphasize. Isaac Lopez Brandon, when he lives in New York, is considered white but when he goes on business to Barbados he’s a person of color again. That ability to see a person’s race is dependent on the rules of the society he’s living in at any particular time. Genealogy does, however, allow us to see a multitude of things going on in our past — things our families have chosen to emphasize and things they haven’t chosen to emphasize.

What’s the reception to your book in Jewish settings?

It seems to resonate with a lot of different people because it’s so concrete. It’s a message people are interested in, in terms of what’s going on with the diversity of Jews, particularly in the United States today.

Do you see U.S. synagogues needing to readjust how they treat Black Jews or multiracial Jews?

There are moments where seeing how things have happened to people in the past can make us more aware in the present. An example in the book is a man from Germany who comes to Shearith Israel in New York in the middle of the 19th century and begins interrogating (the multiracial) women in the congregation: Where are you from? What are you doing here? How did you become members of this congregation? It suggests they don’t belong there. One can only imagine it was a painful moment for those women.

When I teach classes at my children’s day school, I really think, how do the children sitting in that classroom relate to the stories we tell about American Jewish history? Does it give implicit messages of who are the important Jews and who aren’t? The more we can be attuned to that history, which is complicated and diverse, the more we can make it part of the normal vision of what it means to be a Jew in America or in Europe. What are the stories we as historians have told that make people feel they aren’t the important Jews and how does that create feelings of exclusion today?

RELATED: Study: Jews of color love Judaism but often experience racism in Jewish settings