(RNS) — In a scene from a recently released movie, three older women in a small room slowly walk clockwise around a table covered in candles, chanting curses softly.

A scene from the latest “Macbeth” remake? Not exactly: It’s a moment from indie film “A Kaddish for Bernie Madoff,” a musical exploration of spirituality, Jewish identity and the Bernie Madoff case.

Its creator, Alicia Jo Rabins, identifies as a Jewish artist and educator who incorporates elements of witchcraft into her practice of Judaism, an increasingly common, if still controversial, combination.

In both the modern witchcraft and Jewish communities, people are bringing together magic — often called witchcraft — and religious ritual. The ways in which these two seemingly distinct practices merge is often highly personal, depending on heritage, education and spiritual calling.

“The kinds of witchcraft that I practice draw on my training in Jewish ritual,” said Rabins, who holds the Torah in the above scene in the Madoff film. “I don’t see it as opposed to it, but as building on it.”

Rabins, whose upbringing was not very religious, discovered “texts and traditions and the religious rules and laws and ways of living” as an adult and immersed herself in yeshiva.

The more she studies and practices Judaism, she said, the more she also feels the pull of witchcraft or Jewish folk magic — practices she’s caught glimpses of in the edges of Scripture, as well as from Jewish cultures.

Alicia Jo Rabins. Photo © Alicia J. Rose

“My relationship to Judaism is kind of like classically trained, and then with witchcraft, it feels more like I’m just kind of intuiting,” she said.

Rabins admits the two practices seem contradictory, considering that at several points the Torah specifically forbids witchcraft. She interprets these passages as prohibitions against negative practices. The two also overlap in their observance of the natural world: Rabin is a member of a women’s group that gathers for “Rosh Hodesh,” or each new moon, a longstanding tradition in Judaism as well as in witchcraft.

But in an ancient patriarchal society, she said, Jewish leaders likely wanted to set themselves apart from the surrounding culture.

Rabbi Jill Hammer highlighted this point in an interview with Religion News Service, explaining that the difference between Jewish ritual and witchcraft is mostly political.

“Often the way that it’s structured is, if you’re part of the hierarchy … it’s called ritual, it’s called prayer, it’s called ceremony. And if you are doing something outside of the hierarchy, that’s often called magic or sorcery or witchcraft,” Hammer explained.

This distinction was made to shut out particular types of spiritual practitioners and ideas, the rabbi explained.

“Witchcraft is often associated with marginalized people, particularly women,” she said. “There’s a whole body of women’s ritual that tends to be called witchcraft simply because it is women’s ritual.”

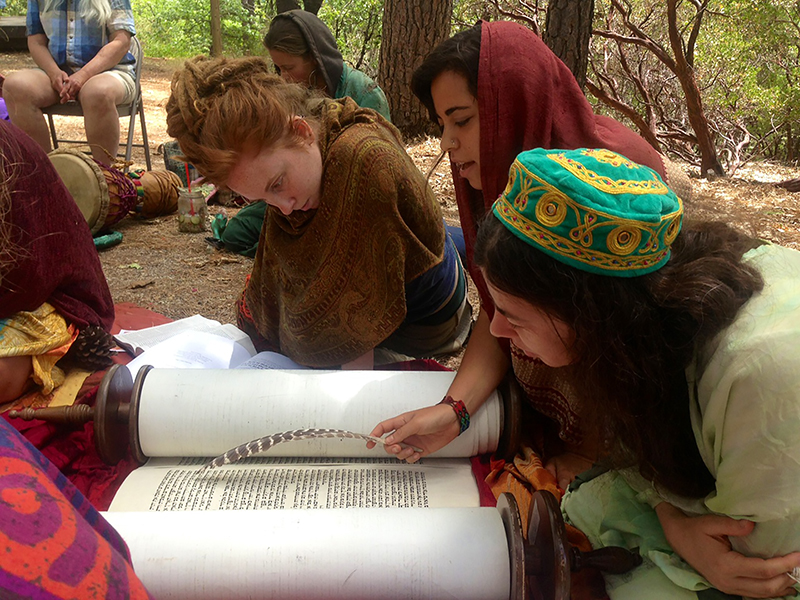

Yael Schonzeit, top right, chants from the Torah during a Kohenet Hebrew Priestess Institute training week in July 2016 in Northern California, while Kohenet co-founder Rabbi Jill Hammer, bottom right, and student Sarah Moser look on. Photo courtesy of Kohenet Hebrew Priestess Institute

Hammer is co-founder of the Kohenet Hebrew Priestess Institute, which seeks to “reclaim and innovate embodied, earth-based feminist Judaism,” according to its website. While Kohenet is not a school of witchcraft, its teachings can include magic as ritual and ceremony within a Jewish context free of political stigma.

“We are not interested in that distinction,” she said.

Once you remove the boundaries between ritual and magic, she added, you realize “it’s not very different from what Jews have been doing for thousands of years.”

The Torah and the Talmud contain many stories of magical ritual traditions, even if such practices were not always sanctioned. Hammer pointed to the Book of Samuel’s positive portrayal of the witch of Endor as an example of how the rules forbidding magical practice were not upheld consistently.

Apart from sanctioned rituals, Jewish folk practices often included healing and protection magic, as well as ancestor veneration, especially during the high holidays. Archaeologists have also found ancient incantation bowls once used to capture demons and expel illness.

Rarely were any of these ceremonies called witchcraft.

Kohenet is working to “reclaim much of these traditions” along with others, according to Hammer, and the institute has attracted people with many different spiritual backgrounds, from rabbinical scholars to Wiccans with Jewish heritage. The ways these clients engage with these ritual practices varies greatly, depending on their background and comfort levels.

RELATED: Jewish priestess movement seeks to reclaim the divine feminine

This variety is evident anywhere you find people who practice Jewish witchcraft. Professional astrologer Aliza Einhorn doesn’t merge Judaism and magic at all. Einhorn grew up in a traditional Jewish household and continues an Orthodox practice. However, along the way, she studied astrology and other forms of esoterica.

A depiction of Jewish gathering for Rosh Hodesh in a German book published in 1724. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

“I was hungry for spiritual knowledge. I wanted to learn,” she said.

While Einhorn does call herself a Jewish witch, she does not seek to define what that means. “Words like witch are fluid and mean different things to different people,” she said. “I do what I do.”

In fact, Einhorn never even used the title Jewish witch until recently, when she stumbled across the term. “It encompassed so much of what I was already doing,” she said, so she adopted it.

However, she still maintains a clear separation between Jewish ritual and magic. “I don’t try to reconcile the two at all.”

But Laura Tempest Zakroff, an artist and author of “Anatomy of a Witch: A Map to the Magical Body,” who lives in New England, sees her witchcraft and Jewish heritage as inseparable. Zakroff calls herself a Jewitch, demonstrating this syncretic relationship through word play.

Laura Tempest Zakroff. Photo by Carrie Meyer

“It describes someone who acknowledges their Jewish cultural heritage and where that intersects or informs their witchcraft,” she said.

Zakroff was raised mostly in her Catholic mother’s faith, but she became strongly connected to her father’s Jewish heritage through history, reading, music and dance.

That heritage comes through in the way she performs her magic, she said. “I know a lot of folks probably (think) the Kabbalah or Qabalah, but to me, (Jewish witchcraft) is the everyday mysteries found within daily ritual — the blessing of a beverage, the honoring of food through preparation. It’s the attention to detail that acknowledges we aren’t alone in this world,” she said.

RELATED: The next stage of witch resistance is here (COMMENTARY)

For Rabins, Jewish tradition gives her spiritual life structure, she said, while other rituals meet her needs in the moment. The connection, however, is seamless in practice: It might mean untying all the knots in the house before a birth, in keeping with Eastern European Jewish rituals, or incorporating plants mentioned in the Talmud into her practices.

“I think that’s part of why it’s easy for me to kind of dismiss the traditional Jewish rules against witchcraft — because I grew up in a place that basically de facto had rules against traditional Judaism,” she said.

“I already kind of broke all the rules I grew up with, and from here on it’s all just kind of searching.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article misspelled “Rosh Hodesh.”