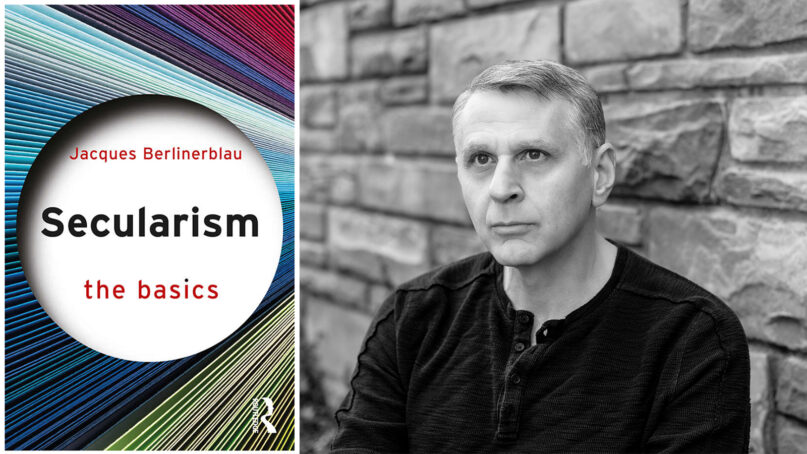

(RNS) — In the United States, secularism has become synonymous with atheism. But that’s a big mistake, argues Jacques Berlinerblau, a Georgetown University professor.

At its core, secularism is an approach to governance, writes Berlinerblau in his new book, “Secularism: The Basics.” And critically, it is one many religious people, not just atheists and agnostics, support.

In fact, although the word “secularism” was first used around 1851, its key components were hammered out long before that by some deeply devout Christians. Among them, none other than Martin Luther, the great reformer, who was so distrustful of the Roman Catholic Church he wanted secular government (in the form of princes) to maintain the law.

In Berlinerblau’s wide-ranging but compact primer, which looks at how various countries have implemented secularism, he outlines the 10 principles of secular government, including equality for all, the supremacy of the state, freedom of conscience and the idea of disestablishment, meaning the government must divest itself of loyalty to any one faith.

Berlinerblau’s book also identifies what he calls “lifestyle secularisms,” people for whom secularism is an identity. Among them, of course, are the so-called New Atheists, who are hellbent on eviscerating religion. That movement, he suggests, has run out of steam.

RELATED: Is God good for America? Depends whom you ask.

But as he points out, among secularism’s champions are lots of religious people, most especially religious minorities. In this country, the overwhelming number of Jews, Muslims, Mormons, even Catholics, champion secularism as a form of government, because they believe it can be a better referee of their liberties than a state church.

Religion News Service talked to Berlinerblau about secularism and why it’s gotten such a bad rap (both from religious conservatives as well as some postmodern scholars who have criticized it).

The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

What’s the opposite of secularism? Theocracy?

Yes, with the proviso that there is a spectrum ranging from extreme forms of secularism to theocracy. On that spectrum are perfectly livable nonsecular states. Then, as we move across the spectrum, we find all sorts of intermediary nonsecular forms of governance where there is lack of freedom of religion for minorities, crackdowns on freedom of speech, lack of tolerance for nonbelievers and heretics, etc. And then we get to out-and-out theocracy: Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Islamic Republic of Iran.

You say in your book that in the United States, separation of church and state is pretty much dead. Where does it figure in the U.S. now?

Separationism is just one form of secularism; it’s one way of doing it. In the U.S., it hasn’t been well thought out, theorized or legally grounded. Here’s the problem: Separationism is not in the First Amendment. In a private letter, (Thomas) Jefferson said we must build a wall of separation between church and state. But with the Great Awakening on the horizon, and with Mr. Jefferson having a reputation as an iconoclast, atheist and a troublemaker, nobody listened to him. Separationism wasn’t really in the judicial mix from 1800 to the mid-20th century.

From 1947 to 1985, separationist secularism, as a binding judicial and legislative framework, was, finally, a real live thing. Under the influence of Justice Hugo Black, our legislators and judges believed there was a constitutional mandate to separate church and state. But that argument rested on a rather wobbly foundation — because, as I noted, separationist secularism isn’t in the Constitution. But that doesn’t nullify secularism or negate the need for secularism in the United States.

The U.S. Capitol is seen at dawn in Washington on Sept. 27, 2021. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

I’ve tried to chart better ways to use the Constitution to render the deliverables of separationism to long-suffering American citizens — be they religious minorities, religious moderates or the religiously unaffiliated, atheists and agnostics. One possibility is the 14th Amendment. American secularism should linger on the amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law. Why should a Jewish woman in Texas be subjected to a conservative Christian conception of when life begins? Why should a gay couple in Kentucky be denied a marriage license because of the religious free-exercise right of a county clerk? I would advise the secular movement to move away from separationism and couch its legal arguments and strategy in terms of equal protection under the law.

Is it more accurate to describe American secularism today as accommodationist?

Yes, it’s more accommodationist than separationist! Few are aware of the shift that occurred when George W. Bush introduced his Office of Faith-based Initiatives and Neighborhood Partnerships as his first executive act in 2001. What Bush was saying is what the Christian right was saying for decades: There was a place for religion in public life and there was a place for the government to accommodate and work with religion because that partnership accrues to the common good.

That’s a core assumption of a doctrine I call accommodationism. Accommodationism’s roots are in India. It comes from the fertile imagination of Mahatma Gandhi and some others. Gandhi believed faith and spirituality were great social assets and the government should encourage and support religion for the greater good of the state itself. When Bush introduced this office, he murdered separationism. Yet strangely, many Americans don’t understand that this shift happened. The American government is now trying to accommodate religion, not separate itself from it.

But accommodationism leaves a lot of unanswered questions: What do you do with religious groups that are violent or seditious or racist or homophobic? Should the government support them, too? Write them a check? But perhaps the biggest problem with accommodationism is what to do about the equal rights of nonbelievers? Can the government “accommodate” atheists and agnostics? If not, why not?

Can secularists turn to the Bible to underscore some of the foundations of secularism?

Secular polities are based on reason, not revelation; science, not suras. But, that said, if secularism were to engage in a PR campaign to win over religious hearts and minds, the idea of everyone being created in God’s image and therefore entitled to being treated equally by the governing authorities — that’s one place to start. I’ve always liked the Book of Ruth and its insistence we should all just get along. Then there’s Romans 13, in which (the Apostle) Paul is urging Christians to submit to the government authorities. He didn’t say become the governing authorities, take over school boards, run for office, storm the Capitol!

To me, the interpretations that are dominant in conservative Christianity run against the grain of many biblical verses.

What are some of secularism’s blind spots?

Secularism sometimes develops an addiction for order at any cost. Enlightenment theorists like John Locke saw the world almost collapse because of religious violence. So their solution was a strong government that assures order. Such a government can assure religious people the right to worship in peace and safety. That’s a very nice idea.

The problem is that secularisms sometimes fetishize order. In so doing they obliterate other secular principles, like freedom of conscience or toleration. The tragic flaw in various secular regimes — the Soviet Union, Baathist Syria, the People’s Republic of China — is the elevation of the idea of order to an extent that verges on totalitarianism.

Secularisms have to learn to control themselves. Governments can’t simply do anything they want. There have to be checks and balances, brakes on the awesome and often frightening power of the state. Secularism goes wrong when it elevates order to the raison d’être of the secular state.

There’s a second problem that occurs when secularisms establish atheism or nonbelief as the “religion” of the state. This is a recipe for disaster and the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China have followed this approach.

You propose a pan-national movement to coalesce people who value secularism. Explain that.

I was struck by a structural asymmetry. Whereas religious groups mobilize across geopolitical boundaries — Islamists, Catholics, Mormons, the Jewish Chabad movement — secularists are always national. It’s puzzling to me that secularism never developed transnational movements or regional movements of like-minded folks who are equally chagrined or discriminated against by a given religious orthodoxy.

I wonder how different things would be if there were a secular caucus in the U.N., led by France, say. These secular countries would look at nations in which religious minorities and nonbelievers are deprived of their human rights or civil rights and advocate on behalf of secular governance rather than the state’s established religion. It’s a thought experiment. The absence of transnational secularism is really, really interesting.

Should journalists make a greater effort to distinguish political secularism from secularism as an identity when writing our stories?

Yes (in italics, caps, and exclamation points)! That was one of the drivers of writing this book. I have nothing but respect for journalists. They have performed heroisms for this country, especially in the past few years. That said, there has been a malignant confusion about these terms — secularism, secularity, atheism, secular humanism — and that’s what I sought to rectify.

RELATED: Dalai Lama says China’s leaders ‘don’t understand’ diversity