(RNS) — This was the best work of Jewish fiction that I read this past year.

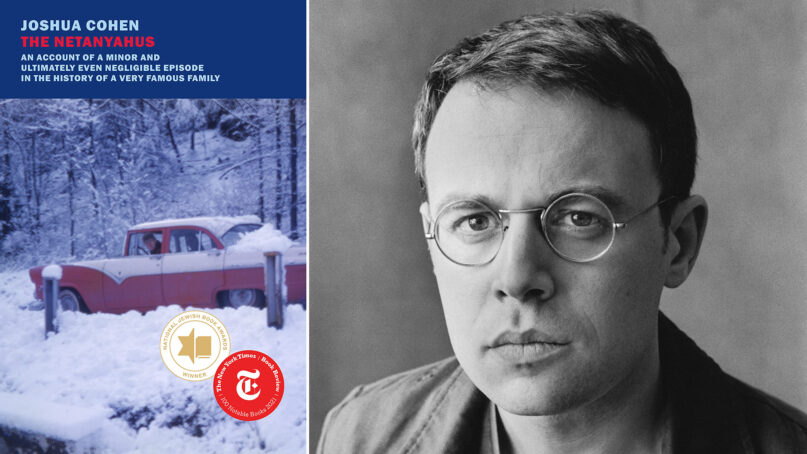

I am not alone in my love. Joshua Cohen has just won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for his novel, “The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family.” It had already won a National Jewish Book Award.

The prize committee called the novel “a mordant, linguistically deft historical novel about the ambiguities of the Jewish-American experience, presenting ideas and disputes as volatile as its tightly-wound plot.”

Why did I love this book? Because it is a novel about ideas — Jewish theology, Jewish views of history and at least one version of the Zionist idea.

“The Netanyahus” is a fictional account of a visit that Benzion Netanyahu made to fictional Corbin College in upstate New York in 1960. The distinguished historian of the Spanish Inquisition was interviewing for a teaching position at the college. (The “real” Professor Netanyahu died in 2012 at the age of 102).

The entire family comes along for the trip: Benzion’s wife, Tzila; the future prime minister of Israel, Benjamin, or “Bibi”; Yonatan (or Yoni), who led the 1976 raid on Entebbe and who died there; and the youngest son, Iddo.

The Netanyahus stay at the home of Ruben Blum, a Jewish faculty member. Craziness ensues.

What is Joshua Cohen trying to say — about Benzion Netanyahu, his legacy, Zionism and American Jewry?

The first possibility: The book is an indictment of the Zionism and worldview of Bibi Netanyahu, through the creation of an origin story for himself and his ideology.

That origin story starts with Benzion, who was not only a noted scholar of the Inquisition but who also served as the personal secretary to Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the founder of Revisionist Zionism.

The novel immerses its readers in the elder Netanyahu’s theories about the origins of the Spanish Inquisition and the origins of racial antisemitism.

Such is the elder Netanyahu’s worldview — what others have called the “lachrymose” view of Jewish history. Wherever we are, we are in trouble.

America was the newest incarnation of Rome, Athens, Babylon, Egypt—Mitzraim. It was Diaspora—galut. And its villains—Pharaoh, Nebuchadnezzar, Antiochus, Hadrian, Titus, Haman, Khmelnytsky, Hitler, Stalin, et al.—weren’t individual men perpetrating individual evil of their own accord, so much as they were all just avatars of Amalek, Israel’s original enemy from the desert. American Jews were just waiting for an Amalek of their own…Carnage was the Jewish destiny and those of us who didn’t survive could at least be sure that those who did would interpret our deaths as foreordained and sacrificial…

To some extent, Bibi inherits that worldview. That becomes his version of statesmanship — aggressive, brash and combative.

“The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family” by Joshua Cohen. Courtesy image

Or, perhaps the novel is saying something else.

Perhaps the novel is not an indictment of Netanyahu, Israel and right-wing Zionism.

Perhaps it is an indictment of American Jewish ambivalence about Judaism, the Jewish people and Israel. Or, as the Pulitzer Committee itself noted: “the ambiguities of the Jewish-American experience.”

Professor Blum is an assimilated Jew. In his upstate New York community, he experiences what we would now call antisemitic microaggressions — vendors talking about Jewish “cheapness,” people wondering about his imagined horns.

Blum describes his New York Jewish childhood as a struggle “between conflicting exceptionalisms, between the American condition of being able to choose and the Jewish condition of being chosen.” Read that several times. It would be difficult to find a simpler depiction of the internal struggle of the modern Jew.

The Netanyahus are bad guests. More than that, they are an embarrassment to the eager-to-assimilate Blum. By the end of the novel, the Netanyahu family has created utter chaos in the Blum household. Yoni, the future hero and sole Israeli casualty of Entebbe, but at the moment a mere stripling lad, has attempted to have sex with Blum’s teenage daughter.

When the sheriff comes to the house to investigate the mayhem, he mutters: “What a goddamned night. Those f-ing people. Excuse me, Professor Blum. But those f-ing people.”

To which Blum responds:

Thank you, Sheriff, and I agree with you about those people. The parents of those boys. They’re Turkish, you know …Turks … what did you expect? … just a bunch of crazy Turks …

“Crazy Turks.” Blum needs to offload the Netanyahus. They’re not Jews, like me. No, they are something else, something even more foreign. Don’t blame me, Blum the New York Jew, for them. I don’t know these people. These are not my people.

I was not a fan of Netanyahu. I disliked his policies, his snuggling up to the ultra-Orthodox, his arrogance, his Trumpian behavior. I am glad he is no longer in power.

But, I did not give Bibi the power to alienate me from Israel itself — any more than I allowed my extreme displeasure with Donald Trump to make a dent in my American patriotism.

For many years, even before its inception, the relationship between American Jews and Israel and Zionism has been complicated. American Jews and Israeli Jews simply understand their respective Judaisms in very different ways — in ways that go beyond politics, parties, personalities and policies.

It is not just Bibi. He is now old news. It is the project of Zionism itself — which would require a larger elucidation that would require another column.

But, I digress. Read the book. It might outrage you, but there is a good chance it will delight you and move you intellectually, in a way that few novels can do.

And, by the way — mazel tov, Joshua!

Your book is the first “Jewish” book to win the Pulitzer for fiction since Michael Chabon’s “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay” — in 2001.

You might just be the heir to the literary throne of the late Philip Roth.

Not so shoddy.