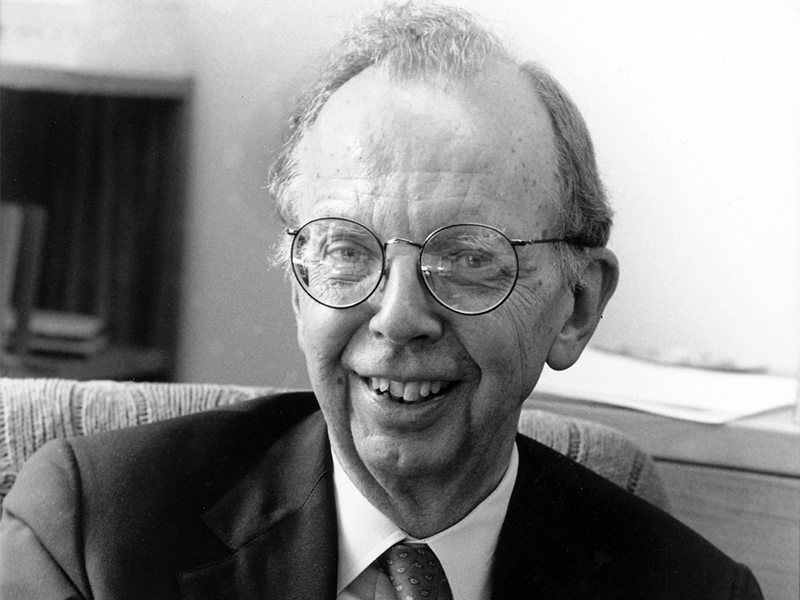

(RNS) — The renowned theological ethicist James Gustafson has been in the news lately, a year after his death at the age of 95, spurred by a fine appreciation of Gustafson’s pioneering work in bioethics by The Hastings Center Report.

It brought to mind my sole encounter with the scholar when I was working at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution 34 years ago. Gustafson had come to nearby Emory University from the University of Chicago to assume a fancy professorship and it fell to me to write the story.

That’s because Gustafson happened to be the godfather of our religion reporter Gustav Niebuhr, so journalistic ethics precluded Gus from doing the piece. Religion scholar manqué that I was, I prepped myself for the interview by reading some of Gustafson’s work and speaking with a few of the distinguished ethicists he had taught over the years.

The interview went as well as I could have hoped but as we were wrapping up it dawned on me — newbie newspaperman that I was — that I didn’t have anything much to grab the attention of your average AJC reader. Aha, I thought, maybe this prominent liberal theologian would have something to say about “The Last Temptation of Christ,” the new Martin Scorsese film that was generating controversy for a scene in which Jesus imagines himself marrying Mary Magdalene and having sex with her.

“What do you think of the film’s Christology,” I asked.

“Jesus undoubtedly had a penis,” Gustafson replied. “He had testicles. He was a good Jewish man. Are you going to sit around and tell me that Jesus was never sexually aroused?”

Wow, thought I, I guess I’ve got my lede — unless the editors think it’s too explicit for a family newspaper. They didn’t and, to the astonishment of a number of my colleagues, the quote appeared a couple of days later on Page 1.

Gustafson, I later learned, was mortified. Here he was being introduced to the denizens of the Bible Belt as a Christian thinker who was OK with a horny Jesus. If any of our readers were scandalized, though, they didn’t write angry letters to the paper or cancel their subscriptions.

As for me, while I felt sorry for Gustafson, I figured I was doing my job. His pushing the envelope of Jesus’ humanity was of a piece with his “Ethics From a Theocentric Perspective,” a two-volume magnum opus that relies heavily on secular learning, very little on biblical authority.

His concern, he told me, was for “secular people who have profound religious sensibilities and profound moral sensibilities but who are put off by the claims of a historically particular religion.”

“When that damn tradition gets in the way of people serving the divine reality, then I’m willing to jettison the tradition.”

After Gustafson died, his student Stanley Hauerwas, perhaps the country’s leading theological ethicist, praised his “tough gentleness.” David Kelsey, his colleague at Yale Divinity School, where Gustafson taught before Chicago, called him “a hard-headed realist about how complex most important ethical questions are. He pushed back against vague and over-simplified rhetorical gestures toward ill-defined abstractions.”

Not that Gustafson expected pastors who admired his work to follow his lead from the pulpit. He recognized that his ideas would never fly in “a traditional community that used traditional symbols and traditional language,” he said.

“If I came out and preached — in a Presbyterian church, in a Methodist church,” he told me, “I’d be out on my ass in no time at all.'”