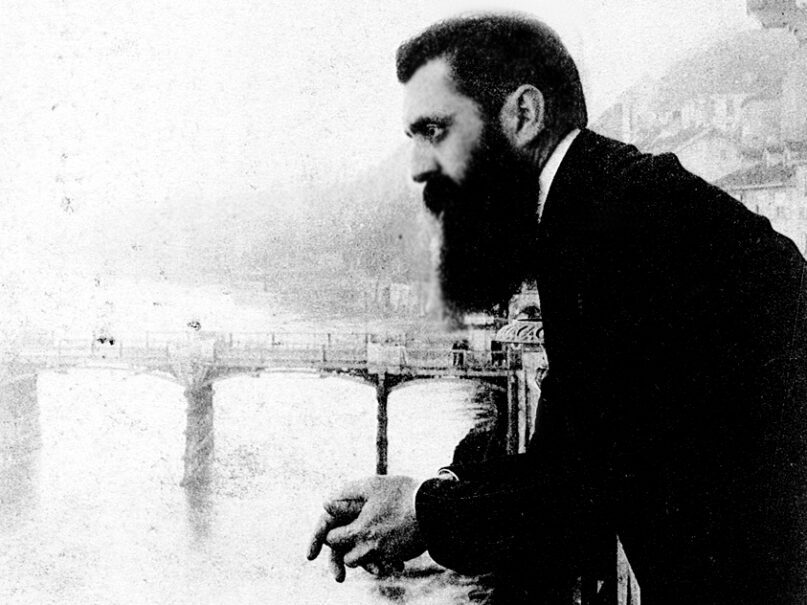

(RNS) — Exactly 125 years ago, a 37-year-old bearded journalist and playwright stood before a formally attired assembly of Jews in Basel, Switzerland.

These are the words he uttered:

“At Basel I founded the Jewish State. If I said this out loud today, l would be greeted by universal laughter. In five years perhaps, and certainly in fifty years, everyone will perceive it.”

The man was Theodor Herzl. The occasion: the First Zionist Congress, the historic gathering of delegates that would create the movement known as political Zionism.

Over the past few days, delegates have gathered in that city to commemorate the anniversary of that meeting. Many of my friends are there, which has provoked within me the 11th plague of FOMO (fear of missing out) — especially as I see my friends on Facebook, posing in the same position as Herzl in that iconic photo.

Oh, yes: about the dress at the First Zionist Congress. You read it right: formal wear. As in tails for the men and evening gowns for the women. Herzl wanted the mood to be festive and celebratory.

Oh, yes: about his statement. He predicted there would be a Jewish state in 50 years. That ranks as one of the most astute and uncanny political predictions of history. He was only off by one year.

A new book by Walter Russell Mead, “The Arc of a Covenant: The United States, Israel, and the Fate of the Jewish People,” provides nothing less than a magisterial (672 pages) history of the American relationship with Zionism. He makes clear that Zionist ideas, or at the very least proto-Zionist ideas, have historically found fertile soil within the American imagination. Therein lies the paradox: While antisemitism has never been absent in American history, there is a layer of philo-semitism that is even richer and deeper.

Mead offers us a world-class discussion of American diplomacy and the competing theories of international policy. The affinity to Zionist ideas carried the day for American support of Israel. More than that: Primary support for Israel originally came from the left, rather than the right — and the Soviet Union, even the Jew-hating Stalin, played much more of a role than we had ever known or remembered.

Mead is also quite honest and forthcoming about Herzl.

In short, his success was a miracle.

Why? Because it is hard to imagine few people less scripted for being a Jewish hero than Theodor Herzl. He was an assimilated Jew from Budapest, Hungary, who had once fantasized of leading all the Jews of Budapest to the baptismal font at St. Stephen’s Cathedral.

To quote Mead:

When his son was born in 1891, Theodor gave him the very German name of Hans and refused to have the boy circumcised. The Herzl family never darkened the synagogue doors … In the modern age opening up, Herzl was sure the quaint Jewish folkways of the past were fated to disappear.

What was it that moved this bon vivant journalist and playwright to understand and embrace the fate of his people?

Herzl was the Paris correspondent of the Neue Freie Presse, a liberal-oriented and prestigious Viennese daily newspaper. He had gotten that job largely on the strength of his travel pieces.

In 1894, he was in Paris to cover the trial of Capt. Alfred Dreyfus, a Jew who had been accused of espionage and treason. Dreyfus was a product of one of Europe’s oldest Jewish families (comedian Julia-Louis Dreyfus is a distant relative). He was, himself, an assimilated Jew. Anatole France said Dreyfus was “the same type as the officers who condemned him. In their shoes he would have condemned himself.”

While Herzl was in Paris, he heard the crowds in the streets, screaming “Death to the Jews!” That was enough to convince him the Jews had no future in Europe and there had to be a place of safety and refuge.

Again, Mead:

The golden dream of assimilation and acceptance had been, Herzl concluded, an illusion. His always active and theatrical imagination perceived a wave of hate slowly building in Europe, and the distinguished and dapper journalist was seized by the conviction that unless the Jews could somehow escape, they faced mass murder and persecution on an unprecedented scale. Finding a way to avoid this fate became the dominant passion of the remaining nine years of his short life; Herzl would transform himself into the leader of the national movement of the Jewish people.

Herzl was right. The Jews would have no secure future in Europe. Fifty years later, the Jews of his hometown, Budapest, would be deported to Auschwitz. Herzl’s youngest daughter, Trude, died in the Theresienstadt concentration camp in 1943.

Herzl’s personal life was tragic. He had a tortured relationship with his wife, Julie. He struggled with serious depression — a malady he “bequeathed” to his children and grandchildren.

Seven years after the Zionist Congress, Herzl was dead at the age of 44. Decades later, his remains would be moved and interred in the national cemetery on the appropriately named Mount Herzl in Jerusalem.

Whenever I walk through the streets of Tel Aviv and Jerusalem … indeed, with every moment I or anyone spends in Israel, we imbibe — no, we inhale — Herzl’s success.

But, paradoxically, for all his success, Herzl also failed.

- Herzl failed to garner European Jewish support. In fact, in their eyes, Herzl was a laughingstock.

Again, Mead:

Assimilationist Jews spent enormous amounts of time convincing their gentile associates that they were as French, as German, or as British as everyone else. Now here came Herr Herzl with his nonsensical talk of a Jewish state, and for the sake of this impossible dream he would put at risk all the acceptance, all the trust that Jews across Europe had labored so long and so hard to win.

- Herzl failed to raise money from Jews.

- Herzl failed to gain the support of the press. The great Jewish newspapers of the day were almost uniformly anti-Zionist.

- Herzl failed to win the support of American Jews. Most American Jews were apathetic at best, and hostile at worst, toward the Zionist idea — and would be for decades.

- Most glaringly, Herzl failed to understand the Arabs of the Land of Israel. He expected the Arabs of the Land would flock to Zionism, seeing its advantages for the development of the Land through Jewish immigration, and therefore for their own economic advancement. But, as Mead wrote, the Jewish contribution to European culture, science and economics had not earned them that much love. Why did Herzl think it would work in the Middle East?

So, how did Herzl succeed, even with all of those failures? How was it possible that he could get face-to-face meetings with the Kaiser of Germany, the sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Pope Pius X, Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria, King Victor Emmanuel of Italy, the colonial secretary of the British Empire and many other leading statesmen of the day? (His travel schedule would put any modern Jewish macher to shame; Herzl’s travel points belong in the Israel Museum.)

It was the power of an idea.

That was what “sold” Herzl to the crowned heads of Europe. Mead again: “In country after country, case after case, Zionism intrigued, interested, and ultimately drew the support of powerful gentile leaders, even as Jewish leaders often wanted nothing to do with it.”

I will go so far as to say: Not since then has a Jewish idea moved so many people.

Herzl got it right: European-style liberalism could not save the Jews. Enlightenment ideas could not save the Jews. Neither could international institutions, nor democracy, nor good intentions. He would have gladly challenged the final words of Blanche DuBois in “A Streetcar Named Desire” — “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.”

No, said Herzl. Only Jews themselves could save the Jews, and Judaism itself.

I end with two reflections on what it meant to be Herzl.

They are both under the category of “you never know.”

First: You never know who will become a Jewish hero. Certainly, Herzl — an assimilated Jew — was not scripted for that role. Nowadays, people would have referred to him with that deeply problematic term “self-hating Jew.”

Let’s remember that Moses himself was luxuriating in Pharaoh’s palace until he saw a taskmaster beating a Hebrew slave and that became his wake-up call.

The lesson: Even, and sometimes especially, “peripheral” Jews can transform Judaism and Jewish life. You just never know.

Second: You never know who will influence you, and whom you will influence. It occurred to me that the real hero of the story was the editor who first engaged Herzl, and therefore sent him to Paris, where he happened to attend the Dreyfus trial.

I always assumed that editor’s name was lost to history.

In fact, his name was Eduard Bacher.

That editor was, in a small way, the founder of political Zionism. He was the one who sent Herzl on his ultimate mission.

Which prompts us to ask:

Who made you who you are today? Who was the heretofore unsung or unspoken hero in your own professional or personal life? Who sent you on your own mission? The teacher, the first employer, the college professor who first suggested you might be interested in … ?

And, whom have you influenced — even more than you know?

To all of us, a happy 125th to Zionism as a political movement!

And, as a belated gift to Herzl, let’s make it even better than it is.