(RNS) — I know exactly where I was 50 years ago today.

I was packing my duffel bag and preparing for my freshman year at the State University of New York, Purchase.

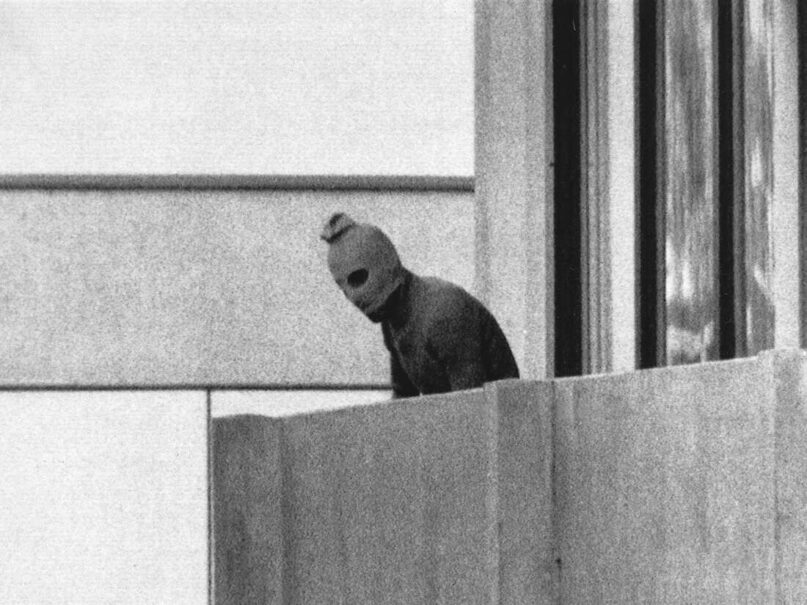

Then, my parents told me what had happened — the murder of 11 Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics, by members of the Palestinian terror group Black September.

That act of terror overshadowed what had happened the day before, which should have been a minor Jewish festival. The Jewish swimmer Mark Spitz won seven gold medals, a world record that remained unsurpassed for 36 years until Michael Phelps won eight at the Summer Games in Beijing in 2008.

That was how I started my college years, and in many ways, it was a preamble for what was to come.

A year later was the Yom Kippur War. Hijackings would give way to increased terror and murder of Jews — a school in Maalot, the attack on Kiryat Shmona, and other places too many to list. In 1974, the United Nations gave a podium to PLO chairman Yasser Arafat, where he brandished a gun in a holster. In 1975, under the influence of the Soviet Union, the United Nations declared Zionism to be a form of racism.

So, my college years were a four-year seminar on what it means for the world to attack and insult Israel and the Jews.

That moment at Munich moved me and it helped define me. I became a Jewish activist on our newly built campus — helping to start the Jewish student group, reaching out to my fellow Jewish students and faculty members, advocating for the first Jewish studies classes. Those experiences pushed me ever more inexorably toward the rabbinate.

It was also in those years when I ended my flirtation with the hard left. In a seminar, a faculty member claimed Theodor Herzl met with Hitler. When I pushed back, reminding him Hitler would have been no more than 15 years old when Herzl died in 1904, my fellow students ridiculed my protest.

I stubbornly clung to my classic liberal ideas. But the growing anti-Israelism and antisemitism of the radical left, especially as I encountered it on the college campus, convinced me there was no place for me in that movement. One of my first published articles (1974, at the age of 20) in Sh’ma was my gett from the hard left.

What was it that moved me about Munich so much?

It was not only the blood and the horror of that event, and that of the massacres that would follow. It was also the stark realization that the world is utterly apathetic about the fate of the Jews.

Many of us know the book “People Love Dead Jews“ by Dara Horn. It is a great book, but that is not exactly what I am describing here. It was not as if the world of the 1970s craved, or even loved, dead Jews.

In the months after the Yom Kippur War, an essay by the literary figure Cynthia Ozick appeared on the cover of Esquire magazine, of all places. Its title: “The whole world wants the Jews dead.” It was an amazing article — and a gutsy move on Esquire’s part to put that on the cover!

I thought the title was overheated. I was hardly convinced the world wanted the Jews dead, though it was becoming increasingly apparent to me it wanted the Jewish state to simply vanish.

No, it was more akin to the title of David Baddiel’s recent book, “Jews Don’t Count.”

To quote Baddiel: “A sacred circle is drawn around those whom the progressive modern left are prepared to go into battle for, and it seems as if the Jews aren’t in it.”

That was it.

No one cheered for the death of Jews. But they weren’t going to break a sweat worrying about it or doing anything about it. It was simply inconvenient — even and especially for many young Jews, who wanted to escape the “caring about the Jews” thing they learned from their parents and grandparents.

The world’s apathy found its personification in Avery Brundage. Brundage became the fifth president of the International Olympic Committee in 1952. He was involved with both the 1936 and 1972 Olympics, the latter of which were the first to be held in Germany since the infamous Summer Games in 1936, which had taken place in Berlin and under Nazi supervision.

In 1936, Brundage had been president of the United States Olympic Association and the United States Olympic Committee (now merged as the United States Olympic Committee). There had been calls for boycott of the Olympics because of the Nazi use of the games as a propaganda forum and because of the racism directed at runner Jesse Owens, who was Black, and Jewish athletes. Brundage would have none of it.

Thirty-six years later, Brundage was still front and center. Before the bodies of the Israelis were cold, Brundage infamously said: “The games must go on.”

As Jeff Jacoby wrote:

Not until 4 in the afternoon, 12 hours after the terrorist attack had begun, did Brundage finally suspend competition for the day and announce that a memorial service would be held the next morning. But at the Olympic Stadium on Wednesday, Brundage spoke only a single sentence about the Jews who had been slaughtered. “We mourn our Israeli friends, victims of this brutal assault.” From that he segued into an indignant complaint about how “commercial, political, and now criminal pressure” was sullying the purity of the Olympic Games. Astonishingly, he described the murder of the 11 Israelis as the second of “two savage attacks” the Munich Games had endured. The first, in his telling, was the decision by the IOC to exclude athletes from white-ruled Rhodesia, a decision Brundage had opposed.

Why? Because, for Brundage, sports was the most important thing — surpassing human rights and, certainly, any sensitivity for Jewish issues. As Carolyn Marvin has written, “fit bodies and competitive spirits were in Brundage’s view essential for the continued success of American capitalism at home and abroad.”

For Brundage, therefore, it was (ahem) “sports uber alles.” Which mirrors American culture perfectly. Sports is the American religion. Ask any rabbi, cantor or Jewish educator: In a competition between a child’s sports schedule and religious school schedule, which will almost always win out?

So, it was the blindness and deafness of the world that got to me. It was Brundage’s valorization of sport — that competition would trump compassion — that got to me.

In the 50 years since Munich, the Summer Olympics have passed without a word of commemoration of the horror. This, despite the lobbying efforts of victims’ families. It was not until last year that there was a moment of silence at the Olympics.

Today, on the 50th anniversary, even as I write these words, the whole world is remembering. Germany and Israel are marking that moment. There are words from German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier and Israel’s president, Isaac Herzog. The German president offered a heartfelt apology — the first official apology for not having secured the athletes. There was a eulogy from the widow of Andre Spitzer.

It is long, long overdue — and urgent.

Because antisemitism and anti-Israelism are still alive and well in Germany, especially among young people. This, despite the fact that Germany has done more than any other European country to honestly confront its past. There is even a term for that struggle to confront the past — Vergangenheitsbewältigung.

Because the massacre in Munich not only represented a tragedy for the Jewish people, and for the state of Israel. It would come to mark the beginning of a new era — an era in which international terror would “graduate” from plane hijackings to the gratuitous murder of civilians.

To put it grimly: Had there been no Munich, there would have been no 9/11.

More than that: This began the era of a loose unity among terrorists — between the PLO and the Baader-Meinhof gang, and others. Four years later, when hostages were taken at Entebbe, it was the work of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, along with two members of the German Revolutionary Cells. Terror was ideological, and it became a franchise operation, as well — at least, where the Jews were concerned. Jew-haters could hang out together, and do their nefarious work together.

In my mind, I go back to those days of 1974 and 1975, when I was a student. Somewhere, there is a photo of a long-haired Jeff Salkin, sporting a button that says: Zachor! (Remember). The word zachor had a drop of blood dripping from it.

A fellow student gently castigated me: “Don’t you think that’s a little … too much?”

I took off the button.

I have always regretted that act. We know what happens, now, when the world decides that Jewish blood “doesn’t count.”

Join me in prayer, whatever faith you are, whatever people or tribe claims you.

These are their names:

David Berger

Anton Fliegerbauer (a West German police officer killed during the gunfight)

Ze’ev Friedman

Yossef Gutfreund

Eliezer Halfin

Yossef Romano

Amitzur Shapira

Kehat Shorr

Mark Slavin

Andre Spitzer

Yakov Springer

Moshe Weinberg

May their memories be a blessing.