Immigrants seated on long benches at Ellis Island. Photo courtesy of New York Public Library

(RNS) — American Jews of a certain generation were long told the United States didn’t do more to rescue the Jews of Europe during World War II because neither the U.S. government nor the general public knew what was happening in Nazi Germany.

A new six-hour series by acclaimed documentary filmmakers Ken Burns, Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein convincingly demonstrates that’s just not true.

“The U.S. and the Holocaust,” which premiers Sunday (Sept. 18) on PBS, covers a lot of ground that would be familiar to most Jews and anyone who has studied World War II — beginning with the efforts of Anne Frank’s father, Otto, to immigrate to the U.S. as the Nazis rose to power. Part 2 extends to 1942, and Part 3 covers the end of World War II and its aftermath.

But unlike many other documentaries about the Holocaust, the Burns series shows those events in light of what was happening in the United States, going back to Congress’ passage of the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which significantly reduced the number of southern and eastern Europeans allowed to immigrate to the U.S. We get a short course in the popularity in the U.S. of the eugenics movement, which attempted to breed out undesirable characteristics of the human race, especially among immigrants, minorities and the poor.

In this way, the series not only dispels the myth that Americans didn’t know and therefore couldn’t act to save the Jews; it asks larger questions about who should be welcomed into the United States and what responsibility it has to people targeted with genocide.

“The U.S. and the Holocaust” poster. Courtesy image

Most damning, the series shows how, in the lead-up to World War II and in its early years, Americans heard on the radio and read in the newspapers about Nazism’s growing menace, its rejection of democratic norms and its rising hostility, culminating in wholesale destruction of European Jewry. Prominent journalists tried to sound the alarm, among them two U.S. journalists who were expelled from Germany for their coverage.

In the end, the U.S. admitted about 225,000 Jews and other persecuted groups; 6 million Jews died.

“Americans had access to a great deal of information about the rise of Nazism, including the persecution and murder of Europe’s Jews,” said Daniel Greene, who curated an exhibit for the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., that inspired the documentary and who appears onscreen.

The documentary, nearly seven years in the making, with loads of period film footage and heart-wrenching interviews with five living Holocaust survivors, brings to life a tragic fact: “The U.S. was a xenophobic, anti-immigrant, antisemitic country in the 1930s when the Nazis rise to power,” Greene said.

RELATED: They’re banning Anne Frank. Are you kidding me?!?!

The documentary unpacks the U.S. State Department’s maddening bureaucratic process for immigration and how difficult it was for Jews abroad to navigate. It shows how many of the policies implemented by the visa division of the State Department, run by Assistant Secretary Breckinridge Long, were purposely slowed and made more burdensome.

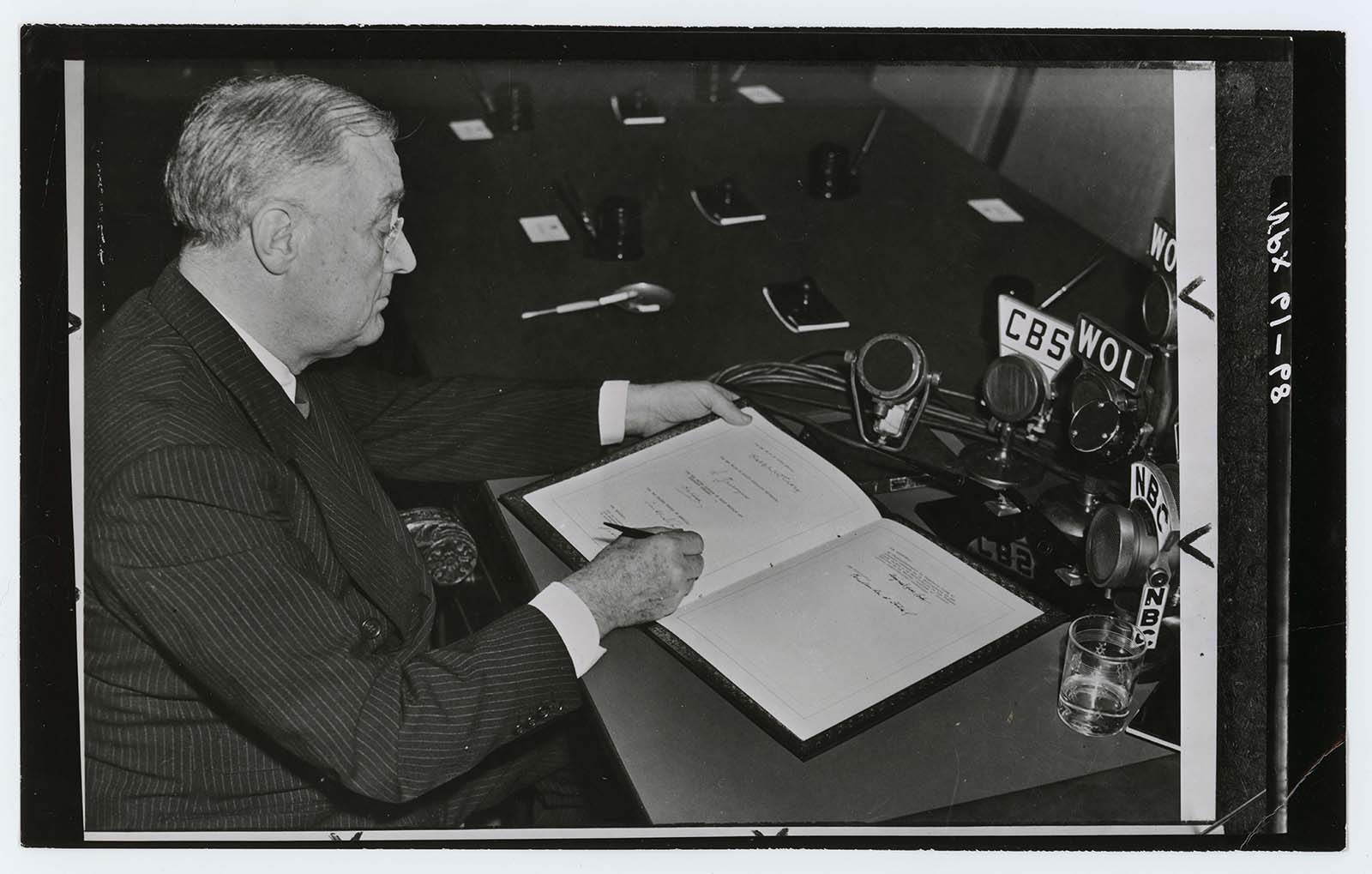

Franklin Roosevelt in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 9, 1943. Photo courtesy of NARA/Creative Commons

Burns does not spare President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who came to power about the time Hitler became Germany’s chancellor, in 1933. Though the film acquits FDR of any personal antisemitism — he had more Jews serving in his administration, for one thing, than any previous president — it portrays his response to the Nazi persecution of Jews as overly cautious. Seeing that Congress was unwilling to make any changes to immigration law, he spent his political capital trying to move the country from isolation to intervention in the war.

“We look back and want him to be humanitarian,” said Rebecca Erbelding, a historian who appears in the documentary. “But he was always a politician. He always had priorities. Those priorities were never pre-war immigration or rescue during the war.”

Jews themselves were not united in how to respond. While some marched in the streets and began a boycott of German goods, other Jewish leaders were concerned that if they protested too loudly about the growing hostilities facing European Jews, they would face a backlash in the United States.

But the documentary also devotes time to the efforts of several U.S.-based groups to aid the Jews, some at great risk, including the efforts of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, now known as HIAS, and the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker group.

One remarkable segment in the third installment of the series focuses on the work of the War Refugee Board, a U.S. government agency set up by a group of lawyers in the Treasury Department to aid the Jews.

Jewish civilians are led by German Nazi troops to the assembly point for deportation. Picture taken at Nowolipie Street, near the intersection with Smocza during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in April 1943. Housing blocks burn in the background. Photo courtesy of NARA/Creative Commons

The group, formed in 1943 long after millions of Jews had already been killed, authorized $15 million in humanitarian aid (about $170 million today). The money was used to buy guns for the French underground, pay off border guards to allow escaping Jews to cross into Spain and friendlier countries, buy boats to get Jews from Romania into Turkey and then British-occupied Palestine and, critically, supply food packages to the camps.

Erbelding, whose book, “Rescue Board: The Untold Story of America’s Efforts to Save the Jews of Europe,” said the effort was massive and important, even if it came too late in the war.

As Deborah Lipstadt, the Holocaust historian and now the State Department’s Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Antisemitism, says in the Burns film, “The time to stop a Holocaust is before it happens.”

In the aftermath of the genocide, the U.S. began to reckon with refugees — a process it continues today.

The documentary concludes with a montage from Charlottesville’s white supremacist Unite the Right Rally, the killing of 11 Jews at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue and the Jan. 6 insurrection.

“Stopping human beings from othering each other and setting up dichotomies of hatred, that is not changing,” said Erbelding. “We do have tools in place. Whether they can keep up with those trying to divide us is the challenge.”

RELATED: Interfaith summit dreams of America as a potluck, not a battlefield