I hope that you will want to learn more about Leonard Cohen and his music. Join me and two special guests for a longer conversation about the religious significance of Leonard’s music. My guests are: Leonard’s rabbi, Rabbi Mordecai Finley, and Professor Marcia Pally, the author of one of the best books on Leonard Cohen — From this Broken Hill I Sing To You: God, Sex, and Politics in the Work of Leonard Cohen.

Click here to listen to the audio — and let us know what you think.

With every passing year, I come to appreciate the late Leonard Cohen more and more.

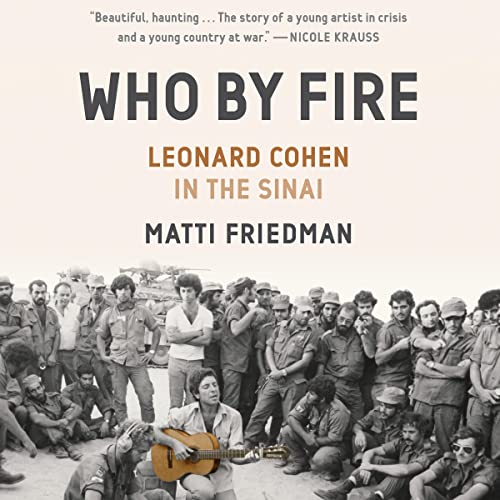

Take, for example, the book that accompanied me to Jerusalem in July — Matti Friedman’s new book Who By Fire? Leonard Cohen in the Sinai.

The book is a treasure. It is the story of one of the lesser known events in the history of rock music, but one that had become part of that sacred lore – Leonard’s visit to the battle front during the Yom Kippur War in 1973.

It was a heady time. When the war broke out, many Israeli singers rushed to the front — among them, Oshik Levi, Ilana Rovina, and in particular, Matti Caspi, who would become one of Israel’s most beloved singers.

When the war broke out, Leonard was living on the island of Hydra in Greece. He went to Israel, leaving his partner, Marianne and his then year-old son, Adam, behind, He thought that he would simply volunteer at a kibbutz.

Leonard was sitting in a cafe in Tel Aviv when Oshik Levi spotted him. Oshik was there with Ilana Rovina,

Oshik turned to her and said, “The guy sitting over there by himself looks like Leonard Cohen.”

“You wish,” she replied.

Oshik said, “I’m serious, it’s Leonard Cohen,” and went over to prove her wrong.

“We invited him to sit with us,” Rovina remembered. “We said we were singers, and asked what he was doing in Israel. He said, ‘I heard there’s a war, so I came to volunteer for harvest work on the kibbutzim and to release a few guys to fight.’ We told him there was no harvest right now, and suggested he come play concerts with us. He said he was a pacifist.”

In Oshina’s memory, two other people were also at the table. One was Matti Caspi, an introverted genius who is now considered one of Israel’s best musicians, but who was then 23 and just beginning to make himself felt…

Leonard demurred, saying that he had no guitar. No big deal; Oshik arranged for a guitar.

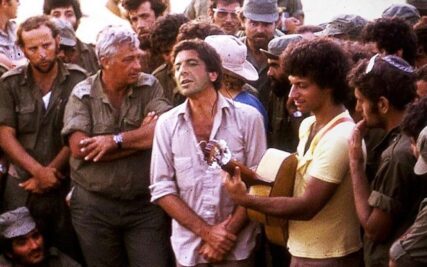

The rest is history — not only rock history, but Israeli history. Leonard went to Hatzor, an airfield in the south. There, he sang — and there is that amazing photo, in which the late general and Prime Minister, Ariel Sharon, on Leonard’s left, and Caspi (on Leonard’s right) accompanies him on guitar.

Friedman writes about Leonard’s effect on the Israeli soldiers:

Some of the men on the sand look up at the visitor with his guitar. Others look down at their dirty knees and boots. Cigarettes glow in the dark. The heat has broken and the desert is still for now. They’ve been fighting for fourteen days and no one knows how many days are left, or how many of them will be left when it’s over. There aren’t any generals or heroes here. It’s just a small unit getting smaller. In the wastelands around them, thousands of Egyptians and Israelis are dead…

When the soldiers join Cohen for the chorus of “So Long, Marianne,” their voices are the only sound in the desert. He introduces the next number. “This song is one that should be heard at home, in a warm room with a drink and a woman you love,” he says. “I hope you all find yourselves in that situation soon.” He plays “Suzanne.” The men are quiet. They hear about a place that doesn’t have blackened tanks and figures lying still in charred coveralls. It’s a city by a river, a perfect body, tea and oranges all the way from China. “They’re listening to his music,” writes the reporter, “but who knows where their thoughts are wandering.”

Leonard had been in a personal and professional funk. His trip to Israel pulled him out of that funk, and it produced some of his best music.

It also inspired Israelis at a time when inspiration was in low supply and in high demand.

Among that best music from Leonard’s time in the war is the song that supplied the title for Friedman’s book, “Who By Fire?”

It is Leonard’s re-writing of the classic liturgical poem, Unetaneh Tokef, which appears prominently in the liturgy for the Days of Awe:

And who by fire, who by water,

Who in the sunshine, who in the night time,

Who by high ordeal, who by common trial,

Who in your merry merry month of May,

Who by very slow decay,

And who shall I say is calling?

The traditional prayer ends with these words: “Through repentance, prayer, and charity [righteous giving], we can transcend the harshness of the decree.”

Contrasting Leonard Cohen’s ending with the ending of the traditional prayer. The things that mitigate against the harshness of the divine decree.

But, how does Leonard put it?

“Who shall I say is calling?”

Here, the interpreter within me goes wild. Are those the words of the worshiper? Does the worshiper no longer have faith in God? Would the worshiper not even know if it was, indeed, God that was calling?

Or, are those words uttered by God’s officious administrative assistant?

Or, is it God?

I believe that it is God.

Judaism is simply this: God’s call – and our response.

Shanah tovah — a good and sweet year to all of you!