Hen Mazzig and I had a wonderful conversation — about Jewish otherness, intersectionality, and the intricate nature of Jewish identity in the world today. Take a listen here.

Check this out.

That was Jewish music. Authentic Jewish music. That was Niggun Yerushalmi, an Israeli folk group, performing the medieval piyyut, a liturgical poem, Ma L’Ahuvi.

If you have never heard Jewish music like that before – if your idea of Jewish music is Freudenthal’s “Ein Keloheinu,” with its musical roots, supposedly, in a German drinking song, or something from “Fiddler on the Roof,” then perhaps it is time for all of us to confess the sin of Ashkenormativity – the widespread Jewish sin of imagining that our central and eastern European Jewish experience is the heart of Judaism. That would be the idea that the Yiddish language, chicken soup, gefilte fish, and stories of the shtetl are essential to Jewish life.

Yes, we are from Berlin and Ukraine…and also from Yemen and Iraq and Iran and Morocco. Those are the Sephardim, but more accurately, they are the Mizrahim, the so-called eastern Jews who come from Arab lands – who today constitute more than fifty percent of Israeli Jews. They have their own stories of grandeur and persecution and pogroms and exile – stories that we almost never hear, and that we almost never honor.

Even though it is where we began. We began in Ur, in ancient Babylonia. The stories of Genesis make that clear: we are constantly returning there. It is where ancient Judaism was shaped during the exile. It is where the definitive Talmud – not the Talmud of the land of Israel – was created. Maimonides himself was a Mizrahi Jew.

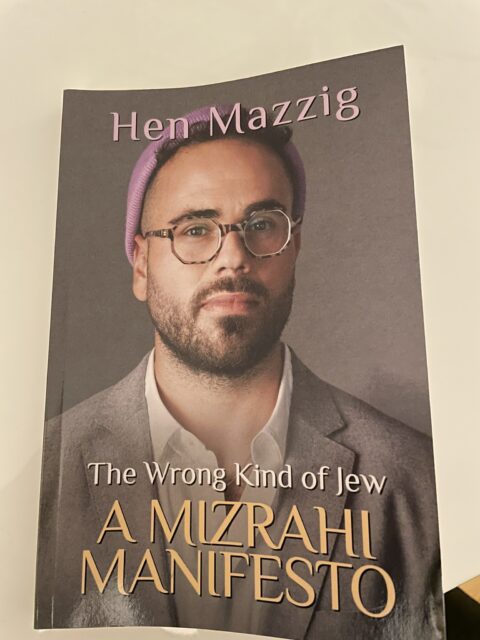

In his new book, The Wrong Kind of Jew: A Mizrahi Manifesto, the author Hen Mazzig writes about his quadruple layers of otherness: a Jew in the world; a Zionist in the world; a Moroccan-Iraqi Jew in an Ashkenazic Jewish world; a gay man in a straight world.

He writes about the persecution of Mizrahi Jews at the hands of the Israeli Ashkenazic establishment, its old political elite that created the state – some of it cruel, some of it subtle, all of it lasting and hurtful. He writes that this is a partial explanation of the success of Likud and the right wing – that those politicians paid attention to the Jews whose identity had been erased twice—once from the earth and then from our collective memory.

He writes:

We are the blind spot in every narrative about our country—including those stories that Israelis have been telling themselves. For decades, we were dismissed by the Ashkenazi elites as a primitive variation of the Arabs who have always been the country’s big “other.”

It is not just in Israel. Hen writes with pain about the fact that there are no American Jewish organizations that are led by Mizrahi Jews.

With similar pain: that there is Yom Ha Shoah, where our memory is mostly Ashkenazic, though Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews also perished. There are no American communal commemorations of the Farhud, the pogroms against the Jews of Baghdad in 1941, under the leadership of Nazi sympathizers; nor of the Jews hanged publicly in that city.

The Farhud, Baghdad 1941. (Yad Yitzhak Ben Zvi Archive)

Hen writes:

While I know the names of many individual death camps in Nazi-era Europe, many of my friends, especially in the United States, have never heard of the Farhud. It is not taught in American Hebrew schools. It rarely appears in textbooks. The Mizrahi victims of the Holocaust have been erased twice—once from the earth and then from our collective memory.

One of my most powerful memories from my year in Israel, studying at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Jerusalem – was the Shabbat when they took us to a kibbutz to meet members of the Black Panthers. These were not the American Black Panthers. It wasn’t as if we were going to be hanging out with Eldridge Cleaver or Bobby Seale, though very few of us would have protested that opportunity.

No – we were meeting with members of the Israeli Black Panthers. They had modeled themselves and their activism on the American Black Panthers. These were Mizrachi Jews, and they were there to tell us about the social gap in Israel. This was already in 1976. I will never forget it.

Neither will I ever forget the term that they taught us – for the forces that they were up against. The term was WASP – not White Anglo Saxon Protestant, as it was in America.

No – they were talking about a different kind of elite.

WASPS were White Ashkenazic Sabras with Protektsia.

Let me unpack this for you.

White Ashkenazic. Someone whose parents or grandparents came from central Europe or eastern Europe. Which is to say: Like most American Jews. Which is also to say: Like many of the founders of the Jewish state.

A sabra is someone born in Israel. That designation had greater social cache than being an immigrant.

Proteksia is a good one. It comes from the word “protection.” It means someone who has social juice, influence, the ability to make things happen. Elite connections.

That pretty much defined the Israeli elite at that time. By the end of our year in Israel, in July 1977, Menachem Begin – who was about as Ashkenazic as it gets – had been elected Prime Minister – and he pledged to pay attention to the Sephardim and Mizrahim – and thus began a social revolution in Israel that continues to this day.

Hen Mazzig writes that Mizrahim had to suppress that piece of their identity in order to fit into white European Israeli society that had no room for them, ethnically or ideologically. And still doesn’t.

The Mizrahim constitute a majority of Israel’s Jews—between three and four million people —and their unique culture and history have had a significant impact on what it means to be Israeli, who Israel’s leaders are, and how the country’s culture looks.

We can ill afford for any Jew to be Other. We need to remember, in the words of next week’s Torah portion, that the Jewish people is like Joseph’s multi-colored garment.

We need to remember that we Jews might be a small people, but we are a very large family.