(RNS) — Some years ago, I was teaching T.S. Eliot’s poem “The Waste Land” in a literature survey class, as I always do. On this day, students seemed even more befuddled by this notoriously difficult poem than usual. After more than an hour of lively and sometimes heated discussion, class ended, and students trickled out. One student who’d been quiet throughout the discussion approached my lectern and said quietly, “I really liked it.”

Surprised (and cheered), I said, “You did?”

“Yes,” he said. “I read it three times.”

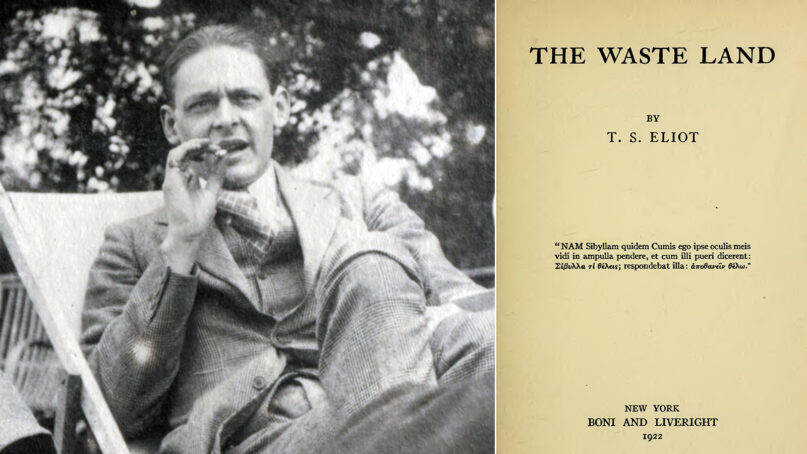

This humble sophomore had discovered the requirement and reward of reading this poem well. Published 100 years ago this month, “The Waste Land” remains worthy, perhaps worthier than ever, of being read, reread and reread again.

To be sure, the work is erudite, complex and dense. Eliot included 433 footnotes for a poem that is 434 lines long. The poem alludes to dozens of other writers, literary works, myths, legends and biblical texts. It has snippets written in Latin, Greek, Italian and Sanskrit. “The Waste Land” is not a poem one reads to be lulled to sleep before bed or to feel cozy on a rainy day.

RELATED: How two poems about the coronavirus went viral by addressing spiritual needs

It is a dazzling, dancing text glimmering with genius and truth which, once glimpsed, changes a reader because the words, like the aurora borealis, reveal something about the world otherwise unseen.

One never sees the month of April the same way after reading:

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

And who today in this polarized, divided, seemingly decaying world would not feel seen when the poet tells us this “heap of broken images” and “these fragments I have shored against my ruins”?

Indeed, the poem’s fragmented, disunified, chaotic structure — confusing to so many readers — is its very point. The very title expresses the modern condition, wrought by the horrors of World War I, its aftermath marked by infertility, abortion, dryness, famine, rape, loveless relationships, failed communication and, of course, death: “I had not thought death had undone so many.”

A modernist poem, “The Waste Land” is not structured the way many of us have been taught to expect in poetry. Indeed, the early 20th century’s modernist movement rejected traditional artistic forms and institutional authorities in favor of innovation, uncertainty and self-conscious experimentation. Written in free verse, the poem lacks regularity in line lengths, stanzas and rhyme. Rather than speaking in a singular, unified voice, the poem features many voices from a range of social conditions and personal situations.

Yet, despite the desolation and decay laid bare in image after image — “under the brown fog of a winter dawn” where “death had undone so many,” “in rats’ alley” where “the dead men lost their bones,” and the “broken fingernails of dirty hands” — “memory and desire” still exist. So, too, does the “sound of water over a rock,” and an echo of thunder, the foretelling of rain and new life.

The fifth (and final) section of the poem, titled “What the Thunder Said,” hauntingly alludes to Christ’s post-resurrection appearance on the road to Emmaus in Luke’s Gospel, wondering, “Who is the third who always walks beside you?”

“The Waste Land” was published five years before Eliot converted from the Unitarian religion of his family to trinitarian Christianity. His baptism and confirmation in the Anglican church at the age of 37 shocked many. Fellow modernist and member of the Bloomsbury Group of artists and intellectuals Virginia Woolf, an atheist, was appalled, writing:

I have had a most shameful and distressing interview with poor dear Tom Eliot, who may be called dead to us all from this day forward. He has become an Anglo-Catholic, believes in God and immortality, and goes to church. I was really shocked. A corpse would seem to me more credible than he is. I mean, there’s something obscene in a living person sitting by the fire and believing in God.

Yet, to read “The Waste Land” is to encounter a soul in search of meaning, a mind grasping the implications of a world with no God. Like other intellectuals at the time, Eliot had thought that art and culture might take God’s place in creating meaning. But he eventually saw the futility of this hope, a recognition powerfully portrayed in “The Waste Land.”

In its end-of-year, end-of-century issue reviewing the 20th century, Time named “The Waste Land” the best poem of the century, describing the work this way: “Filled with post-World War I disillusionment and despair, this allusive, fragmented epic became a touchstone of modern sensibility, and its haunting, haunted language sang the passing of old certainties in a century adrift.”

A hundred years after its publication, Eliot’s description of us late moderns is as apt today as it was then: Our communities are fractured, fragmented and overwhelmed, in many ways, including by death (as pandemic statistics bear out). In his reflection on the poem’s centennial anniversary, The Atlantic’s James Parker writes, “The poem’s discontinuities no longer startle us. Rather, they feel like home.”

Yet even before professing faith in Christ, Eliot seemed to grasp intuitively that this world is not our home. “The Waste Land” reminds believers today that this world should not feel like home.

In the section of the poem titled “The Burial of the Dead,” one speaker asks,

“‘That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

‘Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?”

As Eliot would come to understand, as do all Christians, the corpse that was Christ has risen. Christ has overcome all death rendered by every waste land. The December birthday “The Waste Land” shares with Christmas foreshadows the Easter that is to come.