I remember it, as if it were yesterday.

I remember the first time I heard Steely Dan.

At that moment, I thought to myself: “So, this is what rock music is supposed to sound like.”

It was when I was back in college — back in “My Old School” (which was SUNY Purchase, and not, as with Steely Dan, Bard College).

I can chart my undergraduate years by Steely Dan songs. Freshman year was “Reelin’ in the Years,” “Reelin’ in the Years” is a complex piece of music. It uses almost every note of the chromatic scale. You can forget about those three chord rock songs; this was different, and we could sense it.

Sophomore year was “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number.”

(Listen to this live version of it. Listen to the different changes, and the backup singers. It’s a different song.)

Senior year of college, and lasting into my first year in rabbinical school: “Doctor Wu,” from the “Katy Lied” album.

Steely Dan’s music is that glorious intersection of rock, jazz, funk, a little folk, whatever. It is deeply complex. Just listen to “Aja” again and you will shake your head, muttering: “How the $%#^$ did they do that?”

They did it through sheer perfectionism in the studio.

But, in terms of their lyrics, Steely Dan is all innuendo and sub-text. Even the name of the band itself comes from a William Burroughs-inspired tool of personal intimacy.

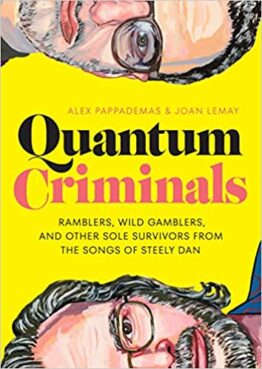

Imagine my utter joy when I opened the new book about Steely Dan — “Quantum Criminals: Ramblers, Wild Gamblers, and Other Sole Survivors from the Songs of Steely Dan,” by Alex Pappademas and Joan Lemay.

This is the finest piece of rock journalism that I have read in a long time. It is up there with the late Paul Williams of 1960s “Crawdaddy” magazine (I still have every single issue of that short-lived magazine, in mint condition); Greil Marcus; and the late Lester Bangs, who was portrayed by Philip Seymour Hoffman in “Almost Famous.”

Steely Dan populated their songs with people who live on the margins of society: drug dealers (“Kid Charlemagne”); strivers for incest (“Cousin Dupree”); a Charles Whitman-type sniper in the bell tower (“Don’t Take Me Alive”), social outcasts and poseurs (“Gaucho“), and various, assorted losers.

The authors speculate about the people in the songs. Plus, Joan Lemay’s wonderful art work depicts what they must have looked like.

As for me, I have long wondered about the following questions:

- Why should Rikki not lose that number? What was it the number to? (There really is a Rikki, the authors tell us).

- In “Any Major Dude Will Tell You,” what is a squonk? What is up with a squonk’s tears? (Don’t worry; there is a wonderful artistic rendition of what one looks like)

- Who is Doctor Wu? What kind of doctor is he?

- What did Katy lie about?

- Who is “The Razor Boy? “(Death?)

- Why is Napoleon in “Pretzel Logic?“

- What is really going on in the song “Kings?” Is it a song that takes place in medieval times, as in King Richard the Lionhearted dying, and King John succeeding him? Or (this is wild!), is it about Richard Nixon losing the 1960 election to John F. Kennedy?

- In “Everyone’s Gone to the Movies,” Isn’t Mr. LaPage showing pornographic movies to kids?

So, what we have here are back stories about the music.

Or, if you will, midrash: musical exegesis. If classic midrash is the filling in of the white spaces between the black letters in the scroll, then this book is a filling in of the silences between the notes in the songs.

There is something metaphorically Jewish in all that, and we should not be surprised.

Donald Fagen — one half of Steely Dan — is totally Jewish. In fact, his parents helped found a synagogue in New Jersey.

Fagen has been known to use aliases — among them, Illinois Elohainu.

Get it?

Only a former Hebrew school cutup could invent something like that.

So, beyond the mysterious Illinois Elohainu, was there anything “Jewish” about Steely Dan’s music?

It is Jewish as metaphor. It is the kind of marginality that we encounter in their lyrics — of people who are totally on the outskirts, looking in, parvenus.

But, let me expose you to a nuance that even the authors missed — and that is the situation of “Peg,” from the “Aja” album.

They might have missed it, but my colleague, Rabbi Ari Lamm, totally nailed it.

In a Rosh Ha Shanah sermon from several years ago, Rabbi Lamm discusses the song “Peg.”

What is really going on here?

He peels back the lyrics, in which a man is encouraging a young girl to make a “foreign movie.”

Lyrically, the song is a conversation between the narrator and a woman, Peg. The narrator encourages Peg to get excited for her debut in the entertainment industry, her name lighting up a grand marquee. “So won’t you smile for the camera / I know they’re gonna love it.” You could listen to the song a hundred times and mistake Peg for a young, up-and-coming Hollywood actress. But coded warnings to the contrary lie scattered across the song. Peg’s audition photo is “done up in blueprint blue,” and the narrator tells the listener in a winking aside that the film is “your favorite foreign movie.” “Blue film” and “French film” were once both popular euphemisms for pornography. All of a sudden, the cajoling tone throughout the song takes on a more malevolent, coercive cast.

You got that?

Then, Rabbi Lamm turns to the prophetic reading for the morning of Rosh Ha Shanah, and re-reads the story of the birth of the prophet, Samuel, from the book of First Samuel.

He notices, as if for the first time, that the story barely conceals the corruption of the Israelite proto-priesthood at the time, in which the priests would “shake down” those who came with their offerings.

So, this is Rabbi Lamm’s move — stunning in its simplicity.

From a barely concealed depravity, hidden beneath the bars of a rock song. To a barely concealed depravity, hidden beneath the words of a biblical text that we hear during theological prime time every year.

And then, Rabbi Lamm moved to the barely concealed fissures in our own society.

Rabbi Lamm, and Steely Dan, inspired me to re-read the book of Ruth, which Jews will hear during the festival of Shavuot, which begins tomorrow evening.

Ruth is a beautiful pastoral story — the story of a Moabite woman who comes to glean in the fields of Boaz, and who becomes the great-grandmother of King David, and therefore the ancestress of the Messiah.

A gorgeous, inspirational story. The Jewish tradition views Ruth as the prototypical convert, the outsider who joins the Jewish people.

And yet, unless we truly listen for it, we might miss this part.

When Boaz invites Ruth to glean in his field:

Boaz said to Ruth, “Listen to me, daughter. Don’t go to glean in another field. Don’t go elsewhere, but stay here close to my girls. Keep your eyes on the field they are reaping, and follow them. I have ordered the men not to — the Hebrew word is naga — you… (Ruth 2:8)

“Naga.” Touch. Harass.

Or, as Professor Jonathan Rabinowitz makes clear — “molest.” The men might have “hit on” Ruth — or, far worse.

That nuance in the story of Ruth had been there all along, and I did not notice it. I wonder how many of us have.

Ruth’s situation is a metaphor for the plight of so many women in our society — unprotected, vulnerable — and yet, ultimately triumphant.

There is far more going on beneath the lyrics of Steely Dan than we had known.

Similarly, there is more going on beneath our sacred texts than we have known.

There is more going on beneath our lines of vision in our own society.

Time to pay attention.