(RNS) — Latter-day Saints make up just 42% of the population of Utah, according to a new study published in the Journal of Religion and Demography. That is far lower than the 60% cited just a few years ago in The Salt Lake Tribune, drawing on 2019 data from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Why the discrepancy between the 2019 figures and the study’s?

They’re measuring different things, say the three sociologists who fielded the sample of 1,909 Utah residents. The church counts as members anyone who’s ever been baptized, even if they haven’t been to a meeting in years. Social scientists, however, measure how many people “self-identify” as belonging to a religious tradition — in other words, those who check the “Mormon/Latter-day Saint” box on a survey, regardless of whether they attend church.

- Rick Phillips

- Ryan Cragun

- Bethany Gull

So there’s always been a gap between the church’s loftier membership figures and the ones sociologists obtain, but that gap appears to be growing, said Rick Phillips, professor of sociology and religious studies at the University of North Florida.

“According to the church’s figures, the Mormon population in Utah peaks at 77% in 1990,” Phillips said. “But in 1990, the National Survey of Religious Identification said it was 69%,” a gap of 8 points. Now that gap has widened to 18 points (the 60% claimed by the church compared with the 42% discovered in the new study).

So Latter-day Saints are losing ground in Utah, and the study’s authors identify several reasons.

“Migration is contributing the most,” said Ryan Cragun, another of the study’s authors and a sociology professor at the University of Tampa in Florida. Whereas in the past, Latter-day Saints would try to find ways to move to Utah, and other people would find ways to avoid moving there, that’s no longer the case. The state’s flourishing economy and proximity to the mountains have proved to be a draw for many who are not Mormon.

“All of this demographic change, all of this in-migration, is religious change,” said Bethany Gull, the third author, an instructor in applied sociology at Utah Tech.

She also points to declining Mormon birthrates.

“It used to be that the first thing anybody said was that Mormons have large families,” said Gull. “I don’t even think we can really say that anymore in the context of Utah. It’s not the large-family state that it once was. Utah is not in the top two, maybe not even in the top three anymore. It’s the Dakotas.”

So Mormons (and other Utahns) are having fewer children — still more than the national average, but not by nearly as much as in the past. In 1980, the authors say, women in Utah had 1.6 children more than the national average. Now it’s four-tenths of a child more.

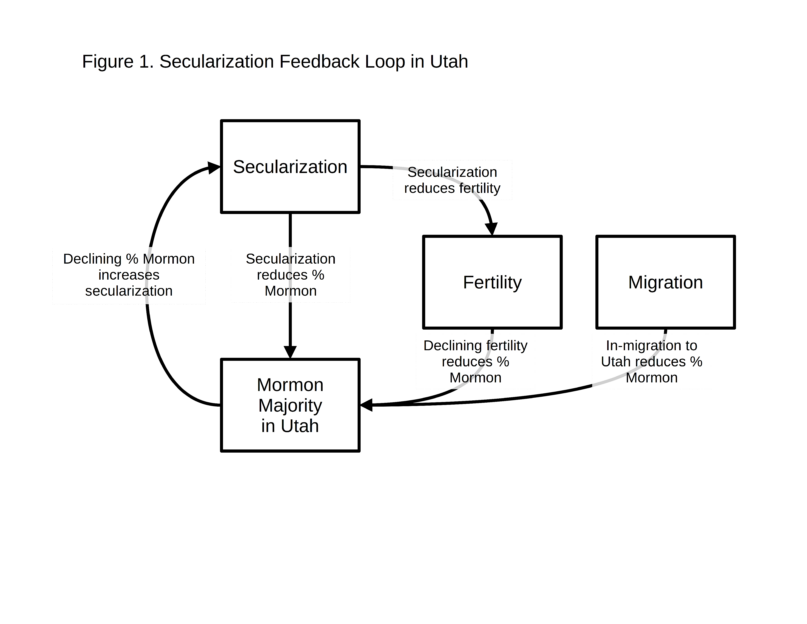

The authors say there are three main reasons why Utah no longer has a Mormon majority: nonmembers moving in from out of state, smaller families and the overall trend of secularization. The three factors catalyze each other, as in this illustration from Ryan Cragun.

In addition to non-Mormons moving into the state and Mormons having fewer babies, more people are leaving the LDS church altogether.

“The social costs are lower now,” Phillips said. “There has been a coercive subculture in Utah that’s been able to keep people tied to the church beyond their subjective commitments to religion, and that’s been sustained by majorities and demography. But now you reach a certain tipping point where people who would never have mowed their lawn on Sunday have enough non-LDS neighbors that they’re like, ‘What the hell? I’ll just go ahead and do it.’”

As the strong religious majority erodes, he said, “the only people who remain self-identified are the ones who have these strong subjective commitments.” Looking at Pew data across time, levels of religious activity among self-identified Mormons have remained constant. So the people who were attached to the church for social reasons are now just inclined to say, “it’s not necessary anymore,” Phillips said.

But they don’t go through the extra step of officially removing their names from the rolls of the church, so they’re still counted in the church’s numbers.

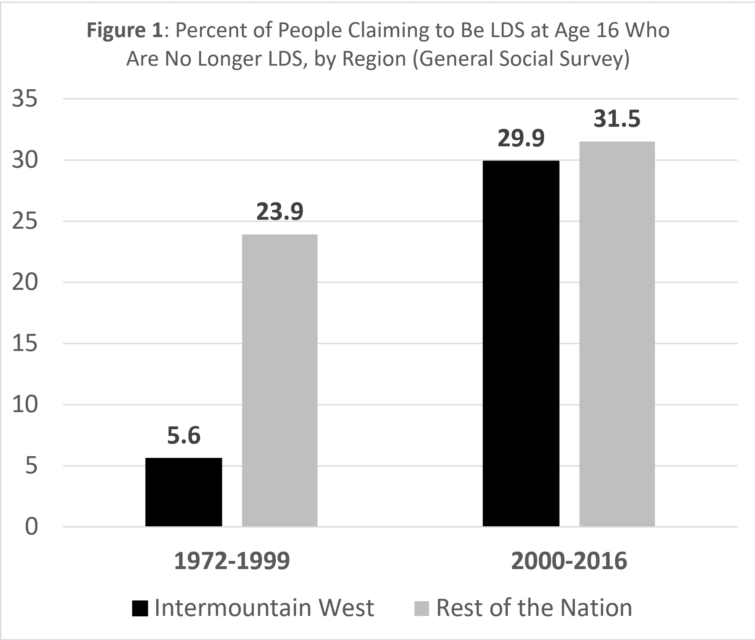

He notes that the church had much stronger retention rates in the past. Data from Mormons born in the early 20th century showed that 94% of people who were raised LDS still identified that way as adults. Sociologist Timothy Heaton similarly reported in the Encyclopedia of Mormonism that data from the 1981 Canadian census showed that only 3% to 4% of people the church claimed as members in Canada did not consider themselves to be LDS.

GSS data on LDS retention from 1972 to 1999, when Utah saw very few people leave The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints compared with the rest of the nation, and from 2000 to 2016, when Utah’s rate of defection steeply accelerated. (Graph and GSS data analysis courtesy of Rick Phillips)

The three researchers say younger survey respondents are more likely to leave, which is similar to young people in the rest of the U.S. But Cragun notes the nonreligious — who used to be reliably male, young, white and better educated than the general population — are looking more like everyone else. They’re more diverse now in terms of age, race, gender and socioeconomic status.

“There are smaller and smaller differences as the nonreligious become a larger segment of the population,” said Cragun, co-author of “Beyond Doubt: The Secularization of Society.” As demographic factors such as race and gender become less important in predicting who is going to leave religion, he points to “value misalignment” as a factor. That’s what happens when modern values such as gender equality and sexual equality come up against traditional religious norms.

“When you belong to an institution that doesn’t share your values, that can cause very serious problems,” he said.

Gull sees this tension now in recent data about LGBTQ equality in Utah, pointing to a 2022 Deseret News survey that showed nearly three-fourths of Utahns supported legal same-sex marriage, a huge jump from earlier years. “If that doesn’t speak to the pushes of secularization and different types of values, I don’t know what does,” she said.

Gull added that one of the most striking findings about Utah’s ex-Mormons is how unlikely they are to join another religion after leaving the LDS church. “People are leaving the church, and they aren’t by and large adopting another religious identity. This is something that needs further study,” she said.

She thinks this may be the byproduct of an idea the church inculcated very successfully: that other churches are in apostasy. “The LDS church is good at undermining the credibility of other churches. From the time you’re very young, you’re taught that this is why we needed a restoration. So maybe it’s not surprising, when you see numbers like that, that more people switch to nothing than switch to another faith.”

Related content:

For US Mormons, religiosity has declined over time, study shows

Is Mormonism still growing? Five facts about Latter-day Saint growth and decline