(RNS) — I am having breakfast with my Aunt Sylvia. She is 92 years old and as sharp as ever. She is a political junkie and activist. I still remember how, when I was a teenager, she became friendly with a 27-year-old man who was running for the Senate from Delaware.

Yes, him. President Joe Biden.

Over coffee, she pulled something out of her bag, and she said to me: “Here, you need to have this.”

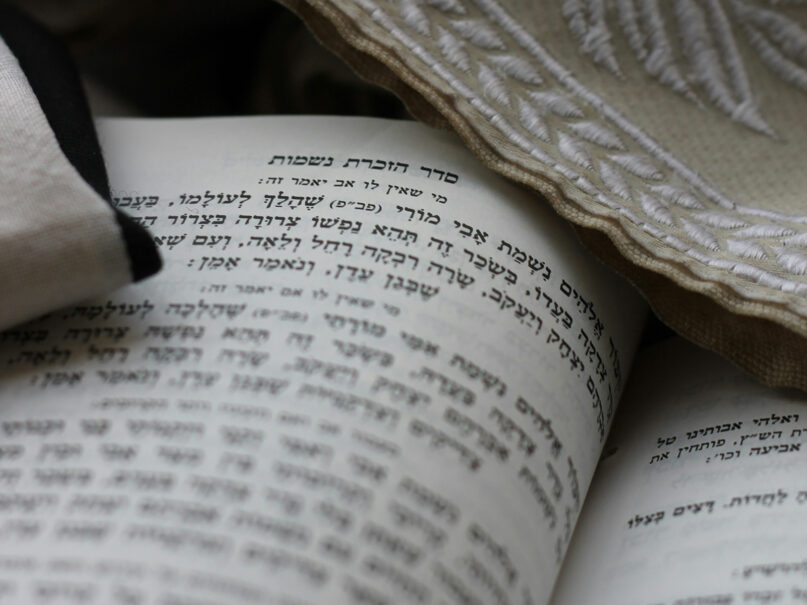

It is an old, tattered siddur (Jewish prayer book).

“Open it,” she says.

My Uncle Sheldon’s bar mitzvah prayer book. (Photo by Jeffrey Salkin)

I did, and I looked at the inscription on the front page. It had belonged to my late Uncle Sheldon and had been presented to him at the Jamaica Jewish Center in Queens, New York, in 1940 — on the occasion of his becoming bar mitzvah. In those days, and for decades afterward, the Jamaica Jewish Center had been a significant Conservative synagogue, with great rabbis and lay leaders.

The title page of the siddur: “Daily Prayers With English Translation,” by Dr. A. Th. Philips. Published by the Hebrew Publishing Company, 77-79 Delancey Street, New York.

It was a very common edition of the traditional Jewish prayer book; you can still find it on Amazon.

As for the Hebrew Publishing Company: back in “the day,” it had been a formidable publisher of Hebrew and Yiddish books — founded in 1883, and housed in the former Bank of United States building on the Lower East Side for over 40 years. (One-bedroom units in that building now sell for between $650,000 and $1,000,000 — not horrific by Manhattan standards, but galaxies beyond anything the great-grandparents of potential buyers could have imagined.)

“I thought that it was better that you should have this than it wind up in a used book sale someday — or worse,” she said to me.

Their children — my cousins — are no longer Jewish, and they have not considered themselves Jewish for decades. Their own children and grandchildren are not Jewish. To put it in poetic terms, those limbs of the Tree of Life fell off years ago.

To continue the metaphor: those limbs fell off. They were not sawed off or hacked off. They simply fell off — because the water never got to them.

“What happened?” I asked Aunt Sylvia.

She proceeded to tell me a piece of my family story I had not quite known. My late uncle was a brilliant man. He knew a lot about Jewish and general religious history.

It is hard to say whether he could have or would have been an active Jew. But, he certainly had it in him to have been an interested Jew — the kind of Jew who attends adult education programs and asks hard questions.

“Here is what I think happened,” she told me.

“Many years ago, we moved to this area. It was your late grandfather’s yahrzeit (anniversary of death). Your uncle wanted to go to the Yizkor service (the memorial service) on Yom Kippur to say prayers for your grandfather.

“So, he went to a local synagogue, and he went into the sanctuary, and an usher approached him. He asked your uncle if he was a member.

“When your uncle said he was not a member, the usher politely but firmly told him that in order to attend that service, he had to be a member or would have had to purchase a ticket for what seemed like an exorbitant amount of money. With that, your uncle stormed out of the synagogue and swore he would never return.”

That is precisely what happened. He never returned — either to that synagogue or any synagogue or any kind of Jewish connection.

The anger was palpable. Almost a half-century ago, I had lunch with my uncle, and he had asked me what I planned to do after my college graduation. I told him I had applied to rabbinical school.

He was appalled. He could not understand how any reasonable person could believe “that stuff.”

My Uncle Sheldon could have influenced the Jewish identity of that family.

I would like to say he dropped the ball.

But, now, I have come to understand he did not drop the ball.

Rather, a somewhat insensitive usher, doing his “job,” had carelessly wrenched the ball out of my uncle’s hands.

I have two emotions I associate with this story: sadness and anger. Sadness that my uncle abandoned Judaism. And anger that my uncle abandoned Judaism because of that synagogue’s quite-common-in-those-days-and-even-now policy.

And, anger that this officious act on a Yom Kippur afternoon had affected not only my uncle, but the rest of his family — and the generations of our family, as well.

What can we learn from this? Many synagogues have dropped those membership/ticket requirements for High Holy Day services. They are seeking to sweeten the waters, to make synagogues more user-friendly, to find different revenue streams — all while trying, often desperately, to maintain financial viability.

But, this is not about business plans and dues models. It is not even about how we balance the twin values of openness and communal responsibility to support our institutions.

This is about something deeper.

This is not about the words; it is about the music.

I wonder; what would have happened if that usher in that suburban synagogue had framed the conversation this way?

“Hi, I’m Jim; welcome to Temple Bnai Whatever. Shanah tovah to you. Tell me your name …

“We are really glad that you are here. We hope that this service is meaningful to you.

“If you like what we do here, and if you appreciate what we are for so many people, I hope you’ll think about becoming a part of our community. We would love for you to be part of our lives.”

I can only imagine that kind of conversation would have drawn my uncle closer to that synagogue. And, in turn, I would have Jewish cousins and second cousins.

Every time Jews pray, they pray the silent prayer with these words: “O my God! Guard my tongue from evil and my lips from speaking guile …”

Translation: What I say has inordinate power — even small, chance conversations.

And, yes: that is the translation of the silent prayer from my late uncle’s bar mitzvah prayer book.

Which I have now decided to make my personal prayer book for my devotional moments.

It is the least I can do for my uncle.

Could my uncle, and others of his generation, have anticipated the massive changes happening in the Jewish world, especially in the wake of October 7? Join me and my colleagues — Rabbi Michelle Dardashti, Jane Eisner and Yehuda Kurtzer — as we discuss American Jewish identity, Israel and Zionism in a special Religion News Service seminar on Feb. 29 at 2:30 p.m. Register here. Hope to see you there!