(RNS) — One of these days, I will write a book on how American cinema portrays rabbis and other Jewish clergy.

I would have a rich database of examples:

- “The Jazz Singer“: a conflict between a traditional cantor and his son, who wants to become a popular singer. (You might prefer the remake, with Neil Diamond and Laurence Olivier.)

- “A Serious Man” by the Coen brothers: three rabbis, representing three generations of rabbi, or three kinds of wisdom. (I prefer the oldest rabbi, because he knew the members of the Jefferson Airplane.)

- “This Is Where I Leave You“: about bereavement and its aftermath, in which there is a brief appearance by a young, cool rabbi.

- “You Are So Not Invited to my Bat Mitzvah“: once again, cool rabbi alert.

- “Crimes and Misdemeanors” by Woody Allen: the classic and the most complex, featuring a wise, kind rabbi who is gradually going blind.

The basic idea of the book? The way American movies portray Jewish clergy reveals our culture’s profound ambivalence about the role of religion and spirituality in our lives.

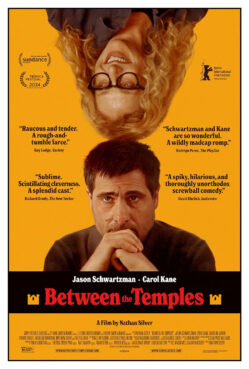

Add yet another chapter in that imagined book, “Between the Temples“: A cantor (Jason Schwartzman) in a small town in upstate New York struggles with the emotional fallout of the death of his wife. He finds redemption by tutoring, and falling in love, with his old music teacher (Carol Kane) who seeks to become an adult bat mitzvah.

“Between the Temples” film poster. (Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics)

It is a sweet movie. The characters are realistic, and for the most part, sympathetic. I felt I knew these people, especially the rabbi (Robert Smigel). It was refreshing to meet the cantor’s lesbian mothers. It was nice to see small-town Jewish life on the screen, as opposed to the larger, more opulent synagogues we usually encounter, whether in the theater or on Netflix. The soundtrack is particularly compelling; mostly, old Israeli pop songs by the likes of Yoni Rechter and the late, lamented Arik Einstein.

Even still, there were some cringe-worthy moments for me, and probably for any learned Jew.

First, the premise of the movie itself — the adult who wants the rabbi to — how does the film put it? — “give” her a bat mitzvah.

I have been playing the linguistic game around bar and bat mitzvah for decades. “I am having my bar mitzvah.” “The rabbi is going to bat mitzvah my granddaughter.” “I am going to Syracuse for the twins’ b’nai mitzvah.” “I was bar mitzvahed in that old synagogue.”

For years, I have been saying (I even wrote a well-known book about the larger subject) that the way we speak about this moment in a child’s and family’s life reveals what we really think about it. It is something to “have.” It is something that is passive, placed upon a child by an older authority figure. The rite of passage itself is synonymous with the ceremony.

I have given up trying to correct the grammar. The notion of a cantor (or anyone) “giving” someone a bat mitzvah is new, even for me.

What is the “best” way of putting it? “I am celebrating becoming bar mitzvah next Shabbat … ”

But the biggest inaccuracy of the movie was also the most telling and the most instructive.

It is where the cantor says Jews don’t believe in heaven.

To which I said, aloud in the theater, “We don’t?”

Granted: Of the three Abrahamic faiths, Judaism focuses the least on the afterlife. Judaism is a profoundly this-world-oriented, life-oriented religious tradition.

But that is the point. Judaism cares so much about life that it has always sought to extend the potential of life beyond the grave.

The Hebrew Bible maintains a relative silence about an afterlife, calling its version of the afterlife Sheol — a shadowy pit where the dead reside and not very much happens.

Fast-forward to the war of the Maccabees against the Syrian Greeks — the story of the Hanukkah rebellion.

In the Book of Daniel, probably written during the wars of the Maccabees, in the 11th chapter, we find these words: “Many of those that sleep in the dust will awaken, and the knowledgeable will be radiant like the bright expanse of the sky, and those who have led the many to righteousness will be like the stars forever and ever.”

It was the most radical spiritual revolution in history. It became the idea of olam ha-ba — the world to come — what most people in the Western world call “heaven.” It appears at every funeral, in the El Male Rachamim, in which we ask the soul of the beloved “to come to rest under the wings of the Divine Presence.”

Robert Smigel as Rabbi Bruce, left, and Jason Schwartzman as Ben Gottlieb in “Between the Temples.” (Image by Sean Price Williams. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics)

(A congregant: “Rabbi, Jews believe in heaven? That’s so … Christian.” Me: “Where do you think they got it from?”)

Recall the Pesach song “Had Gadya”: “One kid that my father bought for a couple of coins. Then came the cat that ate the kid … and the dog kills the cat, and the stick beat the dog, and the fire burned the stick, and the water quenched the fire, and the ox drank the water, and the shochet, the ritual slaughterer, kills the ox …”

And then, the Angel of Death comes and kills the ritual slaughterer. The grand finale of the song: God slays the Angel of Death. Someday, God will defeat even death itself. On that someday, at the end of history, the dead will be resurrected.

That is basic Judaism. Judaism 101. It is what Judaism has believed. That doctrine became a standard part of Jewish belief — so much so, that Maimonides made it one of his 13 principles of faith.

Reform Judaism tinkered with this idea, preferring other alternatives that usually present themselves as: “She lives on in our memories”; “He lives on through all that he did in this world”; “She lives on through this newborn infant that will bear her name.”

All of that is humanly true, and even spiritually true, but Judaism also affirms the reality of a life beyond the grave — even if most Jews do not believe it.

Is it possible that the cantor in the film didn’t know this? Presuming he actually studied for the cantorate, under the auspices of a recognized seminary?

Yes, it is indeed possible he did not know this.

Here is why.

Confession (as we approach the Jewish season of confession and repentance): I didn’t know Jews believe in olam ha-ba — the world to come, aka heaven — until I had been a rabbi for almost a decade.

How could I not have known this, you ask.

Because the topic was never on our seminary curriculum. We learned medieval and modern Jewish theology, but we never discussed this subject. We learned how to perform life cycle ceremonies (somewhat), especially funerals, but we never discussed this subject, though with funerals it stared us straight in the face. Our teachers were the greatest Jewish minds of their generation, but they were largely rationalists. It would take a far deeper dive for me to understand the full richness of the tradition; those great teachers planted some very powerful seeds and those seeds took root.

What did “Between The Temples” get right?

Simply this: the crashing, crushing depression that the cantor experiences in the wake of his young wife’s death. A depression that drives him to lie down on the road, inviting a truck to crush him and end his misery. A depression that causes him to lose his voice.

That depression is real. And, while it was painful to watch, it was good to experience and to validate.

“Between The Temples” is a sweet movie. Go see it.

And, someday, although not soon, may you and your loved ones also enjoy a place in the World to Come.