(RNS) — Everyone knows the song “American Pie,” with that one line: “The day the music died.”

I remember the day my music died — the music of unfettered enthusiasm for Israel’s security and for the American Jewish future.

Or, if you want to quote Don Henley, it was “the end of the innocence.”

It happened exactly a year ago, on Oct. 7, 2023. At about 7 a.m. that Shabbat morning, my phone started buzzing with a message from a good friend. “I am so so sorry about what has happened in Israel.”

With that, I turned on the television. Then began the longest day of my life and of our collective Jewish lives. Oct. 7 is still here. The sun has not yet set on that day.

I have been spending the High Holy Days in Warsaw, Poland. It is difficult to walk more than a few yards without sensing the twin histories of Jewish grandeur and Jewish vulnerability. Leave it to me to find myself here, remembering Oct. 7 in this place of such power and poignancy.

What did I do for myself to remember Oct. 7?

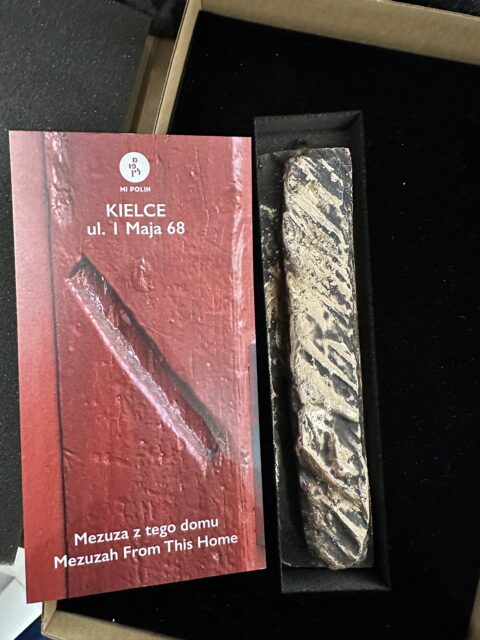

I bought a mezuzah for my new home.

This is not just any mezuzah.

My friend Rabbi Sherre Hirsch introduced me to the amazing work of Helena Czernek and Aleksander Prugar. They are the forces behind Mi-Polin, a mezuzah museum and store in Warsaw.

This is no ordinary mezuzah store. First, it is located down an alley in Warsaw, a few steps away from the last remaining wall of the Warsaw Ghetto.

(Photo by Jeffrey Salkin)

Helena and Aleksander have undertaken an amazing project. They have traveled to various villages in Poland — villages where Jews once lived. They have located the former homes of Jews. They have photographed the doorposts of those homes, where mezuzot used to be.

(Photo by Jeffrey Salkin)

And then, they painstakingly reproduce what the mezuzot had looked like.

I did not expect this visit to grip my soul the way it did. My own Eastern European ancestors lived in Vilnius (Vilna), and not in any of those Polish villages.

So, I chose a mezuzah from another place — Kielce.

(Photo by Jeffrey Salkin)

Before the war, the town of Kielce was home to approximately 24,000 Jews — about a third of its population. Nearly all of them perished in the Holocaust, and by 1946 around 200 survivors returned to live in Kielce. (You can find the full story here.)

On July 1, 1946, a 9-year-old non-Jewish boy, Henryk Blaszczyk, left his home in Kielce without informing his parents. Two days later, he returned. In order to escape punishment, he told his parents that local Jews had kidnapped him and kept him in the basement of the local Jewish Committee.

It did not take much time for Henryk’s story to unravel. Nevertheless, a large crowd of angry Poles gathered outside the building. Both officials and civilians fired upon the Jews inside the building, killing some of them. Outside, the angry crowd viciously beat Jews fleeing the shooting or driven onto the street by the attackers, killing some of them. By day’s end, 42 Jews had been killed and 40 others injured.

It was a pogrom.

Two women grieve over the coffins of those killed in the Kielce pogrom as they are transported to the burial site in the Jewish cemetery in Jul 1946. (U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy Leah Lahav)

Jan Gross quotes an observer:

We hypothesized … that the sight of massacred children and old people must evoke a response of compassion and help. The common fate suffered under the occupation must somehow reconcile them. But we didn’t know human nature … It turned out that our notions about mankind were naïve…

You will ask: Why would you want a mezuzah from a city with which you have no personal connection?

It is very simple and it has everything to do with Oct. 7.

Prior to Oct. 7, the last worst day in Jewish history happened in Kielce.

I am not referring to deaths in wartime, of course; the numbers killed in subsequent wars in Israel would dwarf the number of casualties in Kielce.

I am referring to the unmitigated savagery of citizens toward their Jewish neighbors, the temptation to blood lust, even the fact that the Kielce affair was prompted by a modern blood libel (the suspicion that Jews had harmed young Henryk).

In short, before there was Oct. 7, there was Kielce. And that was what I wanted to remember — especially Jan Gross’ observation: “It turned out that our notions about mankind were naïve.”

Oct. 7 was the day the music died. What other song died that day? The song of naiveté.

It was not only the pre-modern savagery that happened on Oct. 7 — the killings, the burning of children, the taking of hostages, the tortures, the rapes, the sexual mutilation of women, utterly mindless and heedless of whom, exactly, they were killing — among them, Israelis from the Gaza envelope who drove Palestinians in Gaza to medical appointments; peace activists like Vivian Silver; gentle proponents of dialogue and reconciliation like Alex Dancyg.

Yes, those would have been enough to halt my song of naiveté mid-measure, even mid-note.

I lost my song of naiveté about humanity — and, ironically, the humanities. I lost my song of naiveté about the meaning of higher education — that college students and their professors could trumpet and justify the acts of Hamas (and, later, the Houthis). We were dealing with young people who could program their phones and record videos on TikTok. But they are technologically competent barbarians.

I lost my song of naiveté about the American progressive left — our partners in every righteous endeavor — who were not there for us in the moment of our greatest pain. Some of them even celebrated what happened.

I lost my song of naiveté about Jewish education. American Judaism had failed to produce a generation — several generations, really — of young people who could actually carry their own tunes of Jewish knowledge sufficient enough to ward off the unmitigated bulls–t they were hearing on campus.

I lost my song of naiveté about the ability to learn from history. What happened at Kielce was a blood libel, and ever since Oct. 7 the Jewish people have been the victim of one long, protracted blood libel — on campus, in the press and on the lips of so-called progressives.

I gained a few other songs — happier songs, more hopeful songs — about the surge in American Jewish identity. I have sung those songs over and over again. But like the final note of “A Day in the Life” by the Beatles, I do not know how long those songs will last.

So, yes, I now have a mezuzah from Kielce to remind me of how low a civilization can go.

Yesterday, I attended several programs in Warsaw in commemoration of Oct. 7. One was a meeting of educators discussing their work in the fields of memory and resilience. The director of the Jewish Agency in Poland, Yael Branovsky, remarked that since Oct. 7, the Jewish people had been walking with a collective cloud over our heads.

One educator reminded us of the Japanese art form of kintsugi — taking the pieces of a broken vessel, gluing them back together and marveling at the resultant piece of art.

That, she said, is the challenge of living Jewish lives after Oct. 7: taking the brokenness and making it into art.

My new mezuzah from Kielce awaits its place in my home. It, too, is a Jewish version of kintsugi.

It is piece of ritual art that will help me remember.