(RNS) — The Rev. Karyn Wiseman grew up gay in West Texas in the United Methodist tradition, hearing sermons featuring the so-called clobber verses, biblical passages referenced as evidence for why same-sex attraction is a sin. As an adult, she felt called to teach, but the UMC’s 1972 language “that homosexuality was incompatible with Christian teaching” and a later edict that said “no self-avowed practicing homosexual could be ordained in the church” led her to remain quiet about her sexuality and about her longtime relationship with her partner, Cindy.

When same-sex marriage became legal in 2015, Wiseman announced her engagement to Cindy, and within a day, Wiseman said, her district superintendent told her she must resign her membership in the UMC conference or face church trial. Her frustration at not being allowed to be her full self in the UMC led her to the United Church of Christ, where she is now a pastor. Wiseman, who has a doctorate in liturgy and homiletics, recognizes that the pulpit can be a megaphone for either acceptance or condemnation — and, for the queer people in the pews, especially the youth, which message they hear can play a powerful role in their identity.

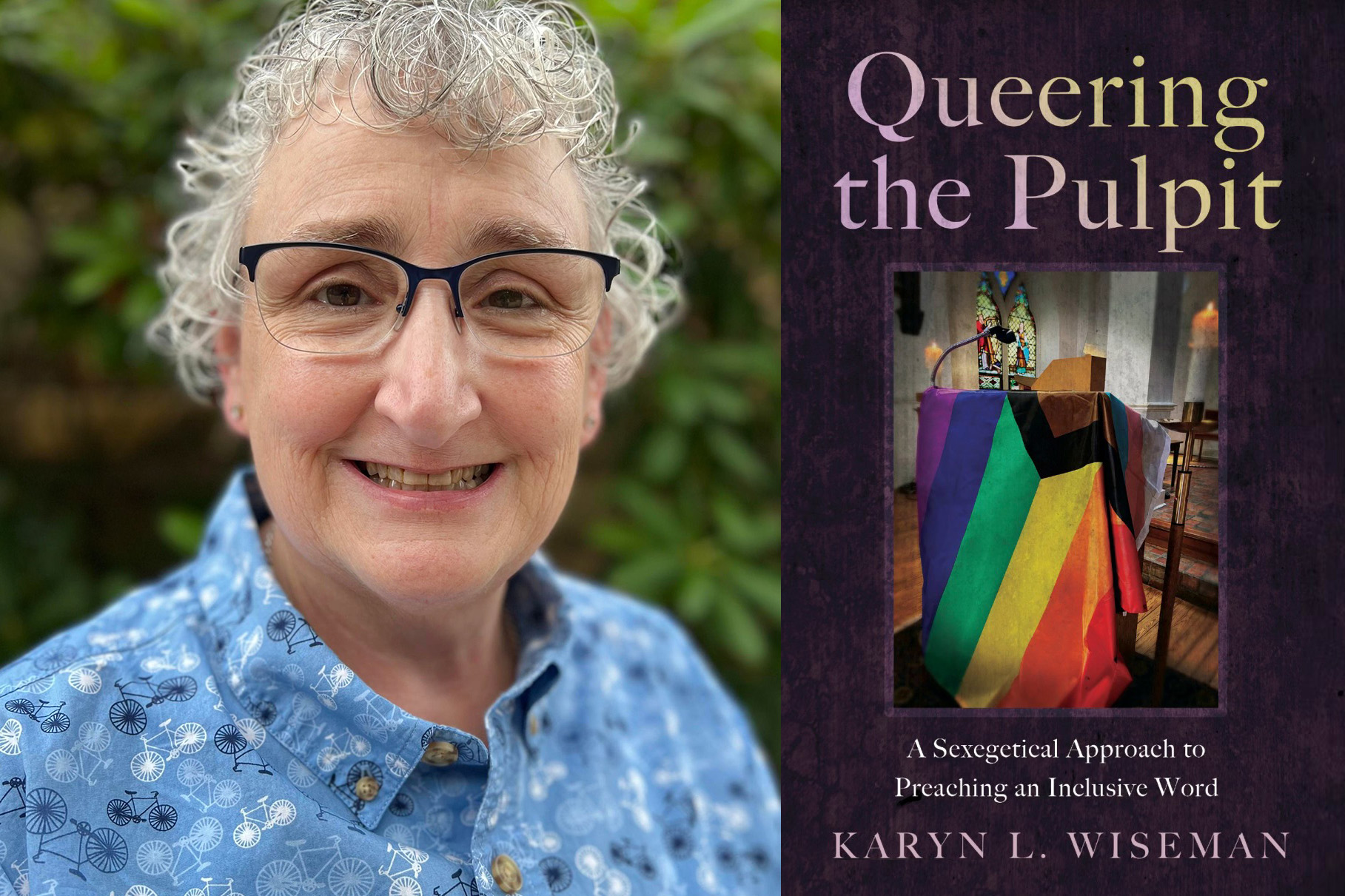

In “Queering the Pulpit: A Sexegetical Approach to Preaching an Inclusive Word,” Wiseman, now in her 60s, implores pastors to implement a new exegetical framework that is conscious of the LGBTQ+ members of their congregations.

“I see this as a personal, pastoral sort of book that’s going to help people, I hope and dream, to think differently about how the church deals with gay folks,” she said.

You write about your journey of leaving the United Methodist Church. Do you see an exodus of people leaving denominations because they don’t feel welcome in the church anymore?

When I was leaving the United Methodist Church for the UCC, I had to take a class on UCC polity and history and theology. The first night there were probably 50-something in the class, and 39 of them were United Methodists who were leaving the UMC because of their stance on homosexuality.

I think there’s been, over the last 20 years, this exodus of members from churches, you know, the decline of the numbers. And when you look at the data, the statistics, a lot of the younger folks, like 35 and below, are so tired of churches squabbling about sexuality, that (some are saying) “I just I’m not gonna have anything to do with the church anymore.” They believe in a deity, they believe in a greater power, but they don’t have anything to do with the institutional church.

Expand on the “sexegetical” framework you mention in the book that you hope pastors will use from the pulpit.

When they craft a sermon, there’s a process that all pastors go through. It’s called exegesis, where they’re looking at the text — the historical, theological, cultural, biblical sense of those texts — and there’s hundreds, thousands of resources out there to help pastors figure out what those texts mean, to interpret for their sermons. What I really wanted to do is take seriously that some of the words we use and some of the interpretation we do does real damage and to ask different questions. With the story of the good Samaritan, pastors, when they preach that sermon, it’s a guilt sermon. Very few decide to tell it from the perspective of the beaten, bloodied man on the side of the road. And so how do you look at that text differently and say, what if he’s queer? What if he got beat up because he’s gay, and the church just walked by, and it took someone of another denomination or another faith to come and help that gay guy on the side of the road? I wanted to figure out a framework so they could ask different questions of the text.

You mentioned this concept of the difference between safe spaces and brave spaces. Why do you believe the church should become more of a brave space?

What I’ve struggled with is that I don’t think you can actually create a safe space, you know, because a Black woman who walks into a white church, there’s no automatic safe space, even if the church said we’re safe. If a gender-nonconforming kid with pink hair and, you know, decked to the nines almost as a drag queen, walks in and they’re the only ones in there, even if there are other people of color. What I want, and I want the church to do this too, is to become braver about talking about homosexuality, about white supremacy, about white nationalists, about transphobia, and to make decisions that say we’re going to affirm all God’s children. And in order to do that, there are hard conversations that have to take place.

In the book, you mention there’s a difference between political versus partisan language from the pulpit. Given that the election is a few weeks away, can you speak about why language from the pulpit is important?

Part of the designation of churches is we’re 501(c)(3)s, so we’re not supposed to tell people who to vote for, how to vote or what party they’re supposed to be a part of. I think when preachers preach and they talk about gun violence, someone will say, you’re being too political. Or, you know, there’s a gay nightclub shooting, and they pray for those folks and read the names of those people, they’re told they’re being political. And for me, Jesus was extremely political. He went up against the religious leaders, against, you know, the Roman leaders. When pastors get up in the pulpit and they shy away from talking about anything because they’re afraid of being labeled as too political, I think they back off so much that they don’t want to make waves, they don’t want to lose their job. The thing is to figure out, how do I preach in a way that says, let’s honor and understand our similarities, our commonalities around human rights and human dignity. That reaches into gun violence, into gay rights, into African American civil rights and Christian nationalism. Those are issues I think the church needs to talk about.

Who do you hope picks up this book, and what do you want them to take away?

I think my first audience probably is going to be my preacher friends, homiletics professors. So, primarily, it’s probably that pastor who already understands being more inclusive — as a tool that can help them do it more. I think it’s for pastors who haven’t figured out why someone comes with lots of trauma to the church and is trying to figure out their understanding of homosexuality. And you know, I think it’s for people sitting in the pew to go, “I hope our pastor will do that.” If one gay kid gets saved because of this, because he hears a sexegetically appropriate sermon, then that’ll be, that’ll be my dream, that somebody reads it, hears about it, is preached differently to, and it changes their understanding that they are indeed a child of God and that the battle’s not hopeless.