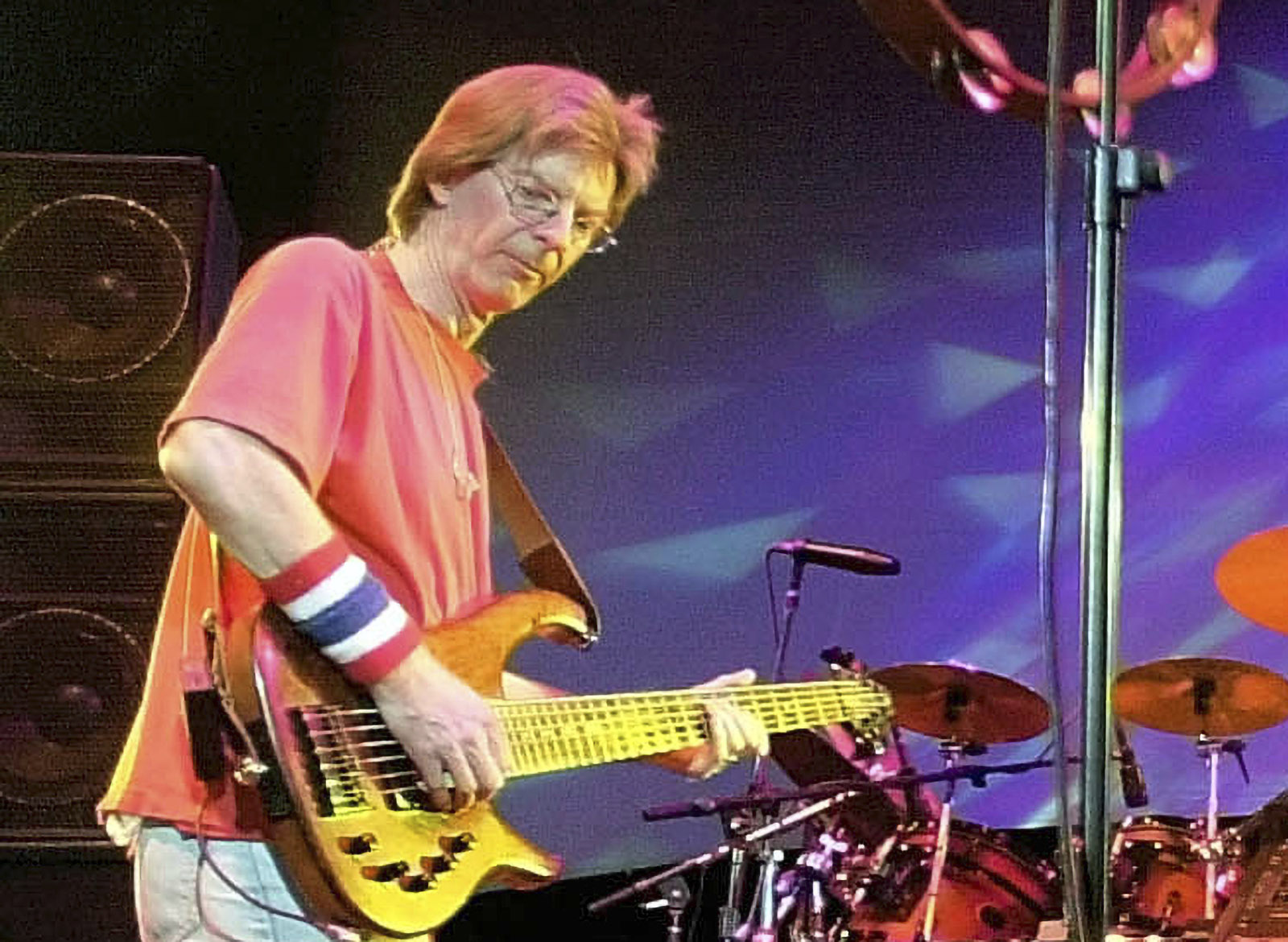

(RNS) — I long thought the Grateful Dead bass player, Phil Lesh, who died Oct. 24, was Jewish. His surname, Lesh, struck me as Jewish, but that’s only part of the story.

Though not Jewish, Lesh was well aware of the large number of Jewish Deadheads, and he honored their presence within the larger Dead community. He held several Passover Seders at Terrapin Crossroads, a restaurant and music venue he had operated with his wife in San Rafael, California — complete with participation by Jeannette Ferber, who had served as the cantorial soloist at Chochmat HaLev, a Renewal congregation in Berkeley.

In 2020, with Terrapin Crossroads closed because of the pandemic, he joined a group of die-hards at a virtual Seder. “I wouldn’t miss this for anything,” he said.

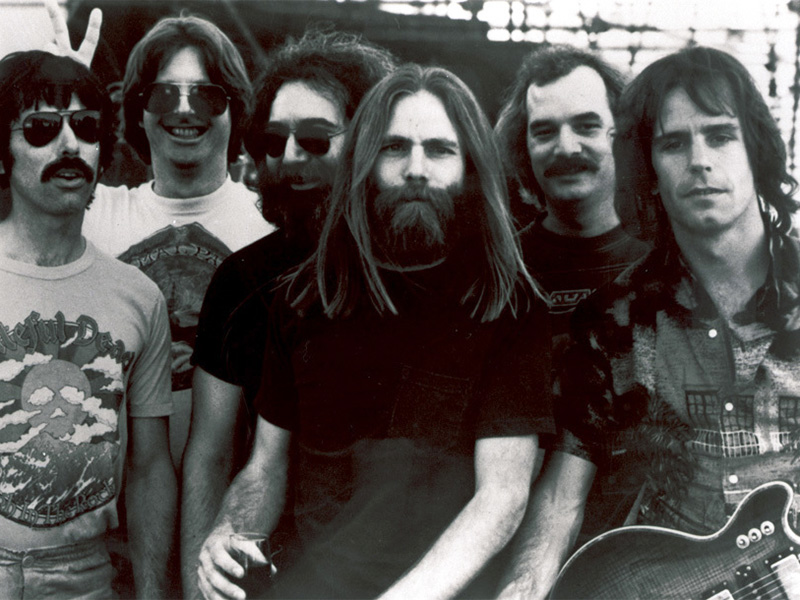

The Dead had other “yichus” (Jewish connections). Bill Graham, the rock music entrepreneur and promoter who was a child survivor of the Shoah and whose mother died in Auschwitz, booked the Dead’s original gig at Fillmore San Francisco. Second, Mickey Hart, who had been one of the Dead’s drummers, was Jewish.

But let’s go back to the Phil Lesh Seders.

He was on to something: He sensed that Pesach, as a celebration of liberation from slavery, contained universal lessons that were potentially meaningful for all people. He might have known, as well, that Passover Seders now, inevitably, involve and include non-Jewish friends and family members.

Me? I struggle with this.

I live somewhere between that yin and yang, between the twin calls of Jewish particularism (“This is about us”) and Jewish universalism (“…and also about the world”).

Yes, Jewish celebrations, by definition, specifically Jewish. They are located in the Jewish calendar and within the context of Jewish history and experience.

But there is that thing about being a “light to the nations,” about sharing our wisdom with the world so that people can feel the resonances within their own lives. So, Shabbat is about sacred rest, and some of my non-Jewish friends have told me that they envy my access to this spiritual gift. Hanukkah is about religious freedom (or, that is how we tell the story now. Let’s face it, folks: The Maccabees were not exactly Jewish liberals). Purim is about the defeat of xenophobia.

And yes, Pesach is about how the Jews escaped Egyptian slavery. It is the quintessential Jewish story, the foundational Jewish story. For Jews, freedom — the liberation of the ancient Israelites — is for one particular purpose. “Thus says the Eternal, the God of Israel: Let My people go, that they may celebrate a festival for Me in the wilderness,” says the Book of Exodus. Pesach is linked inexorably with a larger Jewish religious vision.

But perhaps “you don’t have to be Jewish.” As Michael Walzer wrote in “Exodus and Revolution” (one of my favorite books of all time), the Exodus story features prominently in the German peasants’ revolt, Leninism, Boer nationalists in South Africa, Black nationalists in South Africa, Black civil rights activists in the United States and, of course, Zionism, the classical example of national liberation.

So, yes: I want it both ways. On the one hand, I want to “keep” Pesach for the Jews. On the other, I want to “share” Pesach with the nations of the world. I would like it if all people could hear their stories, and to refract their experiences, through a Jewish lens.

There is more than that to the Lesh Seder. Phil, of blessed memory, knew something deeper. He knew the truth that Arnold Eisen, the scholar and chancellor emeritus of the Jewish Theological Seminary, has taught about Judaism: Jews seek community and meaning.

Members of the Grateful Dead band, from left to right, Mickey Hart, Phil Lesh, Jerry Garcia, Brent Mydland, Bill Kreutzmann and Bob Weir. (AP Photo/File)

Deadheads seek the same things. As Rob Weiner, editor of “Perspectives on the Grateful Dead,” noted:

The Grateful Dead is a good example of people searching for the other, whatever that means, in terms of spirituality — trying to find something that goes beyond their own identity, beyond themselves. It’s an important way to help them live their lives in a moral and reasonable way.

The same is true, and perhaps even more so, with Phish, a jam band often seen as successors to the Dead that has Jewish band members and plays iconic renditions of “Avinu Malkeinu” and “Yerushalayim Shel Zahav.”

Lesh’s Seder affirmed the possibility of a linkage and intersection of two tribes, Deadheads and Jews, and the interplay between those two tribes.

When I learned of Lesh’s death, my thoughts went back to a funeral that I performed, more than a decade ago, for a young man who had been a Deadhead. His parents had requested that I include references to the Grateful Dead in the eulogy.

I was honored to oblige them. I included this quote from “Box of Rain,” the song the late Robert Hunter, one of the band’s most prolific lyricists, wrote in 1970 for Phil Lesh to sing to his dying father.

What do you want me to do, to do for you to see you through …

What do you want me to do, to watch for you while you’re sleeping?

Well please don’t be surprised, when you find me dreaming, too.

Walk into splintered sunlight

Inch your way through dead dreams

to another land

Maybe you’re tired and broken

Your tongue is twisted

with words half spoken

and thoughts unclear

What do you want me to do

to do for you to see you through

A box of rain will ease the pain

and love will see you through.

And so, to Phil, we might echo those words.

“A box of rain will ease the pain and love will see you through.”

Amen.