(RNS) — Picture bacchanalian revels, wine, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll! That’s what people who leave religion are up to, right? Without the moral strictures of religion, and with all that additional time they would have spent on being religious, nothing’s holding them back.

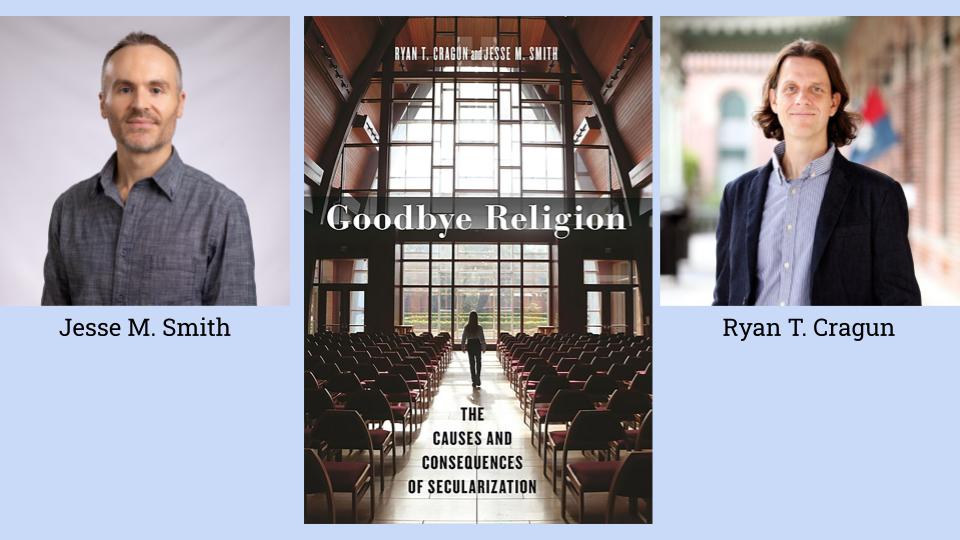

Or maybe not. In “Goodbye Religion: The Causes and Consequences of Secularization,” sociologists Ryan Cragun and Jesse M. Smith say the reality is actually pretty boring. Read on for that finding and six others from the book, an informative and often entertaining read that is chock-full of data and interviews with nonreligious Americans.

They’re actually pretty tame. Despite many religious Americans’ idea that people leave religion because they wanted to sin, “it’s a fairly boring story,” Smith said in a recent interview. He and Cragun studied data about time usage in America and found that nonreligious people use their extra time on Sundays to … do more laundry, basically.

“They’re just doing normal things, right? None of it is crazy. They’re not out at the bars spending hours and hours. They’re spending a little bit more time with their family and a little bit more outdoors. They go hiking, they watch more TV and they get more work done,” Smith said.

Oh, and, according to the book, they might be a tiny bit more statistically likely to be having sex. Perhaps in between loads of laundry.

Leaving religion is not just for white men anymore, if it ever was. In past years, the archetype of someone who left religion was a young, well-educated white male. Today, the nonreligious look as diverse as the general population, a function of more and more people either leaving religion (religious exiters) or being born into nonreligious families (cradle nones). As a result, said Cragun, “Just focusing on demographics doesn’t tell us very much.”

That’s not to say there aren’t other “push” factors, such as being politically or socially liberal. “People are increasingly finding that religious teachings are out of step with their actual political and social beliefs,” said Smith. The authors label this as “value misalignment.” For example, 79% of nonreligious Americans don’t consider homosexual sex to be wrong, but only 45% of religious Americans see it that way. Religious people are significantly more likely to oppose abortion, gender equality and same-sex marriage.

When people experience too much value misalignment and find themselves disagreeing more and more with their religion’s political stances, they’re more likely to head for the doors.

There are also strong “pull” factors. “A lot of the literature looks at deconversion,” Smith said, but focusing only on the “push factors” — the things that people found unattractive about religion — ignores the corresponding “pull factors.” These include having more meaningful things to do with their time, having the autonomy to make their own decisions and being able to embrace a modern worldview.

Younger people are driving a good deal of this. “Generational change is one of the biggest mechanisms of secularization,” Cragun explained. “This is not a ‘failure to transmit’ religion. This is parents granting their kids autonomy, which is a modern value that people have. And as a result, when you give kids autonomy, if they have a choice to go to church or stay home and play video games, it’s not a hard choice for most kids, right? Most kids are gonna make that decision pretty quickly.” Video games for the win.

Even religious Americans may not be as religious as we imagine. In the time usage data mentioned above, only 12% of Americans were doing anything religious on a given weekday, like praying, reading religious texts or attending religious meetings. Even on Sundays, it was only 17%. “That’s it,” said Cragun. “And literally, the survey has got everything. That includes waiting in line to get into your church service, or waiting in line in your car to turn into the parking lot to get into your church service. Like, that’s how detailed it is. It’s a shockingly small number. We were both surprised when we saw this.”

Nonreligious people don’t have a “religion-shaped hole” in their lives. One of the main ideas the authors challenge is that nonreligious people are somehow defective, or that they’re missing the presence of God or religion in their lives. The majority are not, said Smith. “They find meaning in life, they find beauty. They’ll make these sweeping statements about the majesty of the cosmos itself, and about their smallness in it. They talk about how people have to take responsibility for their own destinies and their own lives. They say, ‘Not only is it not bad to be without religion, but I haven’t lost anything. In many ways I’ve gained a wider view.’”

(Courtesy graphic)

Related:

The “nones” are growing—and growing more diverse

New book explores research on how to flourish after being “done” with religion