c. 2008 Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly

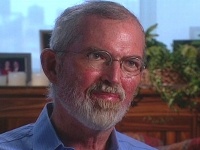

NEW YORK _ Forrest Church is pastor of one of this city’s prominent churches, with two dozen books to his name, an adoring congregation built over 30 years, and a devoted wife and four children.

He also has terminal cancer of the lungs and liver.

He guesses he has less than a year to live.

“I’m being gifted a month at a time, and rejoicing in that,” Church told Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly in a recent interview. “But eventually the treatment will lose its valence, and the barbarians will storm the gates.”

Church, 60, said he was astounded at his reaction to being told he was dying.

“I skipped shock and disbelief and anger and resentment,” he said. “I went directly to acceptance.”

The key, he said, was being able to settle unfinished emotional business.

“The only way to reconcile yourself, make peace with yourself, make peace with your neighbor, make peace with God, find salvation, is to break through and love _ to forgive and to love.

“You don’t change the person you forgive,” he added. “You change your own heart. So anything that you can do to reconcile also means that at the end of your life when you’re _ when you’re given a few months to live _ you can look back without regret.”

Church said the two saddest words in the English language are “if only”:

“If only I had stopped drinking. If only I had dared to change careers when I could. If only I had reconciled with my father when I had the chance.”

Church did have time to say goodbye to his father, the late Sen. Frank Church of Idaho, during his father’s last months. But he concedes he was slow to realize his duty to his family now.

“When I was talking about not having unfinished business, my wife quickly pointed out to me, `Well, you may not have unfinished business, Forrest, but your children have unfinished business. And I have unfinished business. And let’s get down to it,”’ Church said.

“I realized this wasn’t about my death,” he added. “This was our death. And that focused me in on them. This was a time to listen, embrace and say, `I’m so sorry.”’

Church pastored the Unitarian Church of All Souls on Manhattan’s Upper East Side for nearly three decades before stepping down in late 2006 to become All Souls’ minister of public theology. In spite of his illness and treatment over the past two years, he wrote two books, including his most recent, “Love and Death.” He confessed to his congregation one of the reasons for his productivity _ steroids.

“Every week the good folks at Memorial (Sloan Kettering Cancer Center) pumped me full of them,” he said. “For two or three days after treatment I was flying. I haven’t been so high since the late ’60s.”

Like other Unitarian-Universalists, Church rejects many aspects of Christian doctrine. He neither blames God for his illness nor asks God for a cure.

“I don’t pray for miracles,” he said. “I don’t pray to cure my incurable case. I rejoice and consecrate each day that I’m given as a gift.

As to the afterlife, Church said he has “no idea what happens after we die. I go with Henry David Thoreau who, when he was asked about the afterlife, said, `Madam, I prefer to take it one life at a time.”’

At the same time, Church says he has come to believe that without God there is nothing.

“God is what sustains me. I am connected with that grace and power. God is that which greater than all and present in each,” he said.

“For me, Christianity is a faith about love, love to God and love to neighbor that is right at the heart of my very being,” he said. “I am a Christian Universalist. I believe that the same light shines through every religious window. And it’s interpreted. The windows are different. It’s interpreted in different ways. It refracts in different ways.”

Church calls “Love and Death” a coda to his theology, to his “lifelong belief that love and death interwoven were the heartstrings of religion.”

“The greatest of all truths is that love never dies,” he said. “That every act of love that we perform in this life is carried on and passed on into another life so that centuries from now the love carries. And that is the work of religion.”

(OPTIONAL TRIM FOLLOWS)

Church said the opposite of love is not death but fear.

“Fear is what armors our hearts. If our hearts are armored, they’ll never be broken,” he said. “I have seen so many people get hurt in love and then try to protect themselves against it. And when they protect themselves against love they protect themselves against the only thing that is worth living for.

“The secret of it all is that it’s not about me,” he added. “To the extent that we are self-conscious and self-absorbed we cannot be conscious of the world around us, of God, and of our neighbors. ”

Church said “one of the beautiful things” about a terminal illness is that your friendships become stronger. “Your loved ones become more vital and present. Each day becomes more beautiful. You unwrap the present and receive it as the gift it is.

“You walk through the valley of the shadow, and it’s riddled with light.”

KRE/JM END ABERNETHYEditors: A version of this story first appeared on the PBS program Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly. Please use the Religion & Ethics Newsweekly byline.)

875 words, with optional trim to 700

A photo of Forrest Church is available via https://religionnews.com.