On his visit to Turin this week, Pope Francis became the first pope to visit a Waldensian house of worship. He also became the first pope to apologize for the persecution of the Waldensians by the Catholic Church.

So who are the Waldensians and why did Francis visit and apologize to them? And is there any particular significance to his doing so?

The Waldensians get their name from Peter Waldo, a rich clothier and merchant of 12th-century Lyons, who as a young man experienced a radical conversion and decided to embrace “the apostolic life.” He turned his property over to his wife, gave the rest of his possessions to the poor, and began preaching and teaching publicly about the virtues of simplicity and poverty — with the help of a translation of the Bible into the vernacular. Within a few years, he acquired followers, who called themselves “the Poor of Lyons.”

In 1179, Waldo visited Pope Alexander III to get his approval for the new movement, but while the pope embraced him, his ideas were condemned as heretical later that year at the Third Lateran Council. What most seemed to bother church authorities was that Waldo and his followers presumed to teach the Christian message, and that they did so as lay people, traveling in mixed company out in the world. At a time when the apostolic life was considered to be the sole province of monks, canons, and nuns living celibate lives under fixed rules, this was scandalous. It didn’t help that the Waldensians went around criticizing church leaders for living high on the hog.

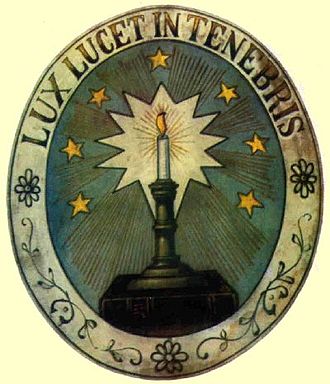

In due course Waldo was himself declared a heretic, and although he had made a perfectly orthodox profession of faith at a diocesan council in Lyons in 1180 or 1181, he and his followers seem to have developed unorthodox views — rejecting belief in transubstantiation and purgatory, for example. In subsequent centuries, the sect hung on in the Alpine regions of France and Italy, though severe and often violent persecution by the Church and its secular minions kept their numbers low.

The Waldensians are now thought of as forerunners of the Protestants, and in fact, when the Reformation came along, the surviving members signed up. Today, the 30,000 who remain identify with the Reformed tradition of John Calvin and Ulrich Zwingli. But it is more accurate to regard them, in their origins, as forerunners of the Franciscans.

Waldo himself was very like St. Francis in turning as a young man from a well-to-do bourgeois existence to a life of poverty and service to the poor. His followers, like the early Franciscans, lived on the charity of the people among whom they preached and taught. It was recognized at the time that Pope Innocent III decided to authorize Francis’ new religious order in 1210 because of Waldo’s success.

Making friends and amends with the Waldensians was thus not just another bit of ecumenical outreach for the present leader of the Catholic Church. In speaking of the possibility of collaborating with them on “service to humanity which suffers, to the poor, the sick, the migrants,” Francis showed he knew that they are very much Christians after his own heart. Indeed, had Alexander III been as enlightened as Innocent III, the present occupant of the See of Peter might very well have named himself not Pope Francis but Pope Waldo.