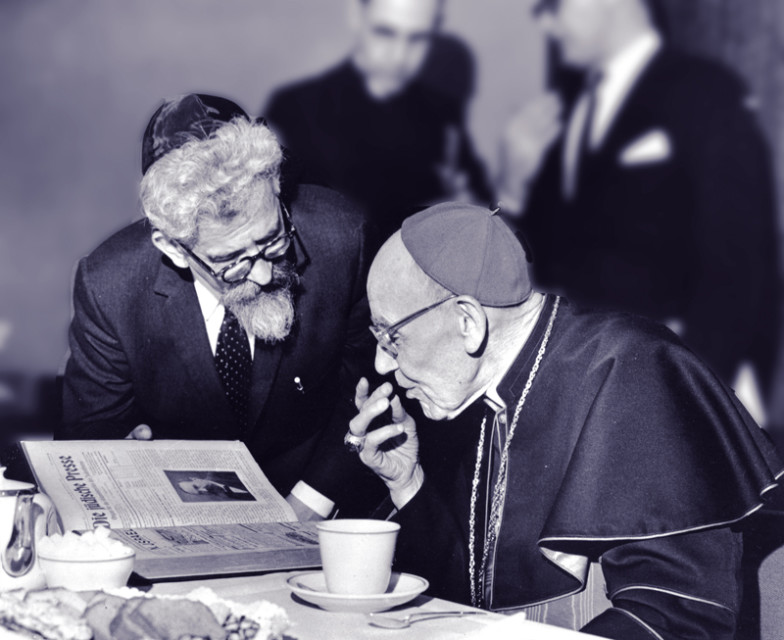

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel meeting in New York with Cardinal Augustin Bea, who shepherded the process of Catholic introspection that led to “Nostra Aetate,” on March 31, 1963. Photo courtesy of American Jewish Committee

The ‘Splainer (as in “You’ve got some ‘splaining to do”) is an occasional online feature in which RNS staff give you everything you need to know about current events to hold your own at a cocktail party.

(RNS) The Vatican on Thursday (Dec. 10) released a document that for the first time explicitly advises Catholics not to attempt to convert Jews. It goes on to affirm the common roots of Christianity and Judaism and marks the 50th anniversary of “Nostra Aetate,” the landmark Vatican declaration that established a new rapport between Jews and Catholics.

The Anti-Defamation League — founded to protect Jewish lives and rights — has called the church’s approval of Nostra Aetate “arguably the most important moment in modern Jewish-Christian relations.” How so? Let us ‘Splain …

Q: “Nostra Aetate.” Does that mean “Jewish people” in Latin?

A: It means “In Our Time.” They are the first words of the declaration, which was written during the Second Vatican Council, the most far-reaching reform effort of the Roman Catholic Church in centuries. The document’s English title: “Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions.”

In the fourth of its five sections, Nostra Aetate focuses in on the relationship between Jews and Catholics. By the way, the entire declaration is a quick read — little more than a page long.

Q: Yeah, but could I have the Cliff Notes version?

Q: Yeah, but could I have the Cliff Notes version?

A: Nostra Aetate draws a poetic analogy between Christians and Jews, describing them as the “well-cultivated olive tree onto which have been grafted the wild shoots, the Gentiles.”

Crucially, it rejects the charge that the Jewish people are responsible for Jesus’ death, an accusation used for centuries to justify the persecution of Jews. The document reads: ” . . . what happened in His passion cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today.” The church, it continues, “decries hatred, persecutions, displays of anti-Semitism, directed against Jews at any time and by anyone.”

Q: Does Nostra Aetate mention the Holocaust?

A: No, but it was born of it. French Jewish historian Jules Isaac survived the Holocaust and then immersed himself in Christian texts, trying to understand how Christians could participate in Hitler’s plan to murder the Jews, or stand by as millions perished. He concluded that a misinterpretation of the Gospels, a “teaching of contempt,” had provided an excuse to persecute Jews for centuries, and that it must be supplanted by a teaching true to Jesus’ message.

In 1949, Isaac met with Pope Pius XII, whose response to Nazism is viewed by critics as too slow and too quiet, and remains a point of contention. Little came of the meeting. Ten years later, Isaac met with Pope John XXIII, admired for his efforts to save Jews during World War II. John, who had already thought deeply about Christian responsibility for Jewish suffering, entrusted Cardinal Augustin Bea, a champion of Jewish-Catholic relations, to lead the effort to draft a declaration on the church and the Jews.

Q: Does Nostra Aetate talk about religions other than Judaism?

A: As originally conceived, the declaration was to be about the church and the Jews only. Traditionalists, and Middle Eastern bishops unsympathetic to the new state of Israel, objected. Bea decided on a less contentious goal: a document that stressed ecumenism and discussed other faiths.

Hinduism and Buddhism each get a complimentary line or two. And the third of Nostra Aetate’s five sections is devoted to Islam. “The Church regards with esteem also the Moslems,” it states. “They adore the one God, living and subsisting in Himself; merciful and all-powerful, the Creator of heaven and earth, who has spoken to men.”

Q: So after Nostra Aetate, everything is hunky-dory between Catholics and Jews?

A: Issues have arisen, including the Vatican’s reluctance to establish diplomatic relations with Israel, which occurred in 1993, and the pursuit of sainthood for Pope Pius XII. But since Nostra Aetate was signed, all popes have taken seriously its charge to improve Jewish-Catholic relations. And in 1998 the Vatican apologized for its inaction during the Holocaust.

As for the current pontiff, even before he was Pope Francis, Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Buenos Aires enjoyed a close friendship with Argentine Rabbi Abraham Skorka. The pair co-hosted a television show and wrote a book together about interfaith dialogue. These days, when Skorka visits Francis at the Vatican, the pope himself is known to supervise their meals, so that the rabbi eats only kosher food.

YS/MG END MARKOE