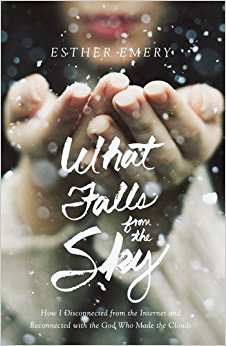

A few years ago, Esther Emery was not a believer but she was burnt out. In a “desperate attempt for a reset,” she decided to take a year hiatus from technology. Surprisingly, her digital fast leads her into a profound experience with the Risen Christ and the faith she had previously rejected. Her book, “What Falls From the Sky: How I Disconnected from the Internet and Reconnected with the God Who Made the Clouds,” chronicles this experience and argues for an approach to technology that makes space to encounter God anew.

Her message is especially relevant at this moment. Holy week is in full swing, and on Sunday those who call themselves “Christian” will celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ. We Christians believe that the resurrection, among other things, allows humans to experience God in the here and now. But often obstacles arise in our lives that hamper our connection with God. Could technology be one of those obstacles?

Here, Emery and I discuss how she thinks about technology’s moral dimension and what she hopes to change about her readers’ lives.

RNS: Before we being talking about your experiment, I’d like to know what you think about the morality of technology. Do you think technology is mostly beneficial, mostly damaging, or neutral.

EE: I think technology is neutral. To me, it’s an issue of access. Being very connected means that you are giving access to yourself to a number of parties that are not neutral, including many who have a financial interest in keeping your attention as long as possible. But being disconnected means giving up your own access, particularly to information about situations that are not in your own personal space. The goal as I see it is to have as much maturity as possible in handling this technology, and how it interfaces with our lower as well as higher impulses.

RNS: You were an atheist before you decided to unplug. Tell us about your transformation.

EE: I completely credit my year without internet for my conversion to Christianity. But that is not because I think cellphones are secular, demonic things. It’s simply that it’s hard to make an about-face change like that when people are watching you. Even if I did have certain ideas or a deep feeling of longing, I couldn’t change my identity to a Christian identity.

Stepping into a room without mirrors changed all of that. It became a matter of the soul on the inside, not a matter of my reflection in mirrors. And at that level it was a completely worthy and beautiful journey. It was more a love story than anything. I just fell in love with Jesus, and I wanted more.

RNS: And then? How did unplugging from the internet improve your connection with God over time?

EE: I discovered a kind of silence that was essentially synonymous with prayer. It turned out to be, anyway. In the silence, I experienced this awareness that I was so, so tiny, and something else out there was so, so big. It was overwhelming and beautiful and I always felt better afterwards. It took me a while to decide to call that something the presence of God.

That discovery wiped clean whole generations of obstacles to faith for me. Issues of political and cultural identity just faded away. There was a very pure sense of the challenge: can I accept forgiveness and healing when it costs me my ego and the prideful feeling of being the god of my own universe? Can I accept this opposite of loneliness — this deep, deep sense of belonging and refuge — when it costs me my feeling of intellectual control? It changed the whole map for me, of what it means to be a person of faith.

RNS: Speaking of prayer, did unplugging affect your approach to spiritual practices?

EE: During my year without Internet, I read 100 books and wrote the titles down. And there were more after that, as I was becoming less concerned with counting things. I read and read and read. Even several books that I would have considered too dense or difficult, including the entire Bible, came to feel more manageable.

And silence, similar to meditation, became a part of my daily routine. You could also call that practice “it’s dark and I’m very alert and there’s nothing else to do.” It was a moment in my day that I always used to fill with scrolling on the Internet. But I learned to appreciate how that kind of silence cleared my mind and brought healing to my heart.

RNS: Many people use the internet to connect with their friends. Did disconnecting rob you of connection with loved ones?

EE: It puts the locus of control very much in your own hands. Disconnecting from social media and email means that you will not accidentally run into people. If you need someone to be with you — to hear how they are doing, or to tell you what they’re thinking – you have to go to them. There are obstacles to that. Most notably, pride and selfishness. I definitely went through periods of isolation. But I came through them and was able to connect at a deep level with some important people.

Also, I connected more deeply with people of a prior generation. It revealed to me how much the Internet contributes to generational divides. My husband’s grandmother became an important pen pal. I spent time with older people at my church. Because these people were not as accustomed to using the Internet to interact, they were more available to me during my unplugged time, and the way that turned my attention towards them was a precious gift.

RNS: You said your marriage was a rocky when you started your experiment. How did disconnecting affect your marriage if at all?

RNS: Well, it saved it, really. Again, the decision to invest in that relationship had to be entirely my own. Disconnecting from technology didn’t create a will to stay married any more than participating in social media creates a will to be a good friend.

But the open space and silence gave us an opportunity to be together again. We found solace in the very ordinary moments, of making dinner and sitting together after dinner, and rebuilding comfort in small ways rather than always trying to handle the big shards of our hurts and disagreements.

When we did finally address our deepest hurt it came out of a long period of silence: the willingness to just be together, making bread in the kitchen. Hearing an honest apology out of that kind of restful silence was incredibly healing. It did what no 10-decible argument could ever have done to give our marriage another chance.

RNS: What do you think about technology and children? How would you encourage parents to be more intentional with their children’s use of technology?

EE: There’s a great deal of shaming around technology and children. That’s not very helpful, and I don’t want to be a part of it. But I do love that for children there is joy to be found in physical things. They love to be in nature. They love to make things. They can cook and bake and craft. And to the point that their maturity allows, children can self-entertain and use their own creativity to find pleasure in the world.

I would encourage exactly the same for children as I do for adults. Is there some time of rest built into the day? Are we allowed to rest? Do we model for our children that it’s okay to rest? (Even resting from entertainment.) Do we give kids practice feeling silence and knowing how not to panic when the screens go dark?

RNS: Having completed this experiment, what advice would you give all the tech-obsessed Christians out there? What changes should they make?

EE: I recommend to anyone a practice of 10 or 15 minutes of daily rest. It’s possible to access silence in this time, but I don’t know that it helps to enforce silence. It’s kind of a tricky thing. Turn everything off that beeps or makes noise. Maybe even turn off the artificial lights — the ones you’ve almost forgotten were artificial.

If this seems impossible or miserable, maybe try spending that time looking out the window. I also recommend dusk to dawn unplugging. Going off the Internet at dusk and not turning it on again until the dawn is a very healthy, manageable practice that I still do today.