Guests tour the new exhibition, “Pilgrim Preacher: Billy Graham, the Bible, and the Challenges of the Modern World,” at the Museum of the Bible in Washington on Aug. 11, 2018. RNS photo by Menachem Wecker

WASHINGTON (RNS) — In the 1950s, 1 in 3 verses that Billy Graham used to anchor his sermons came from Jewish Scripture known to Graham — and most Christians — as the Old Testament. With each ensuing decade, however, America’s pastor drew increasingly on the New Testament.

The decrease in Old Testament citations, said Anthony Schmidt, an associate curator at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., reflects Graham’s relative concern about the threat of communism through his career. As the Cold War was still taking shape and Graham’s anti-communism was egged on by, among others, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, Graham drew upon fire-and-brimstone Old Testament admonishments. As the Red threat dissipated, he sought biblical citations with a softer tone.

The findings are part of the museum’s new exhibition, “Pilgrim Preacher: Billy Graham, the Bible, and the Challenges of the Modern World,” which Schmidt curated.

Poring over about 1,300 sermon notes from “America’s pastor,” Schmidt found that 33 percent of the verses around which Graham built his sermons came from the Old Testament in the 1950s but that the percentage dropped in each following decade: 29.06 percent in the 1960s, 25 percent in the ’70s, 21.59 percent in the ’80s, 17.05 percent in the ’90s and 9.62 percent by the 2000s.

“If we don’t get our act together here in America, the communists are going to come bomb and kill us,” Schmidt said, characterizing the sermons before the shift began in the late 1950s. “He begins to slow down with that type of rhetoric, and he emphasizes God’s love instead of judgment.”

The last pulpit used by Billy Graham is in the new exhibition at the Museum of the Bible in Washington. RNS photo by Menachem Wecker

The exhibition, which runs through Jan. 27, contains about 100 objects related to Graham’s crusades, as he called his revival-style evangelistic meetings. There is the suit that Graham wore on his final crusade in 2005, his traveling case, personal Bible, sermon notes and artifacts of his broadcast ministries.

The display is bookended by two pulpits that are on view for the first time, according to Schmidt: a plain, wooden traveling pulpit Graham used on his first major crusade in Modesto, Calif., in 1948 and the one from which he preached his last sermon on July 9, 2006, at Baltimore’s Camden Yards at age 87.

Anthony Schmidt, an associate curator at the Museum of the Bible. Photo courtesy of Anthony Schmidt

The latter pulpit, adorned with a cross and designed to accommodate a chair so Graham could sit, contains an inscription from Nehemiah 8:4, “And Ezra the scribe stood upon a pulpit of wood, which they had made for this purpose.”

The museum set out to humanize and historicize, but not to deify Graham, according to Schmidt, who admits being disappointed to find that the handwritten notes in the margins of Graham’s New Testament were often “just short words” and what seemed like random underlining. “I was hoping it had something profound, like, ‘Here’s the answer.’ There was nothing like that,” Schmidt said.

The sermon index Schmidt has created from the sermon records held at Wheaton College in Illinois (and which he intends to make public) was revelatory, however. Other scholars who have studied Graham also found the new research compelling. A sermon index of Graham’s preaching is something that Bill Leonard, an emeritus professor at Wake Forest University’s Divinity School in Winston-Salem, N.C., has wanted for a long time. “I love this, and I can’t believe they went to the trouble to do it,” he said.

Leonard looks forward to studying Schmidt’s index when it’s available, but the finding that Graham scaled back his Old Testament quotes is consistent with what Leonard knows about the preacher. “Graham, in his sermons, moved from legalism to gospel, or from legalism to Jesus,” he said.

Barry Hankins, professor and chair of the history department at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, also finds the sermon index fascinating and potentially significant.

When one preaches, as Graham did, about America being in covenant with God, according to Hankins, the natural place to cite is the Old Testament, where lines can be drawn from the Israelites’ covenant with God to America’s.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Graham admitted that he had identified America too closely with Christianity earlier in his career, Hankins noted.

“As Graham’s preaching moved away from the Christian America ideal, he found the Old Testament, perhaps, less and less useful to what he was preaching about,” Hankins said.

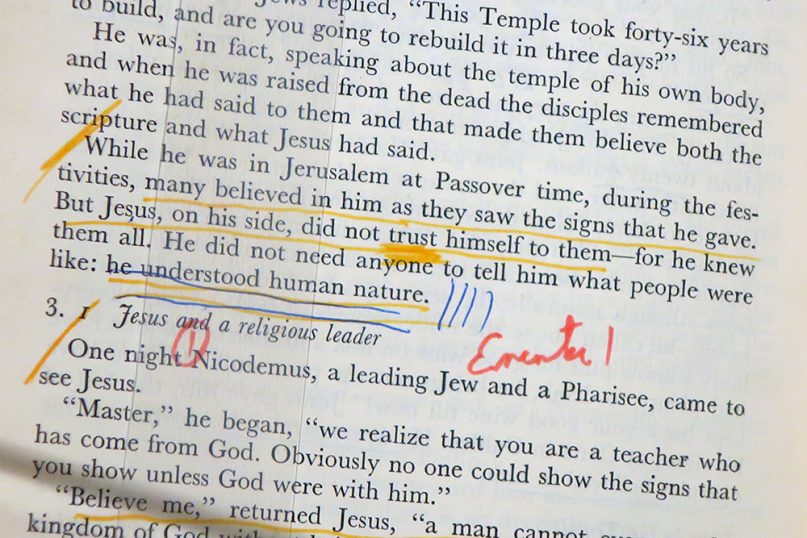

Details from the Gospel of John in a Billy Graham Bible at the new exhibit “Pilgrim Preacher: Billy Graham, the Bible, and the Challenges of the Modern World,” at the Museum of the Bible in Washington on Aug. 11, 2018. RNS photo by Menachem Wecker

Though he agrees that Graham seemed to find the Old Testament more relevant when preaching against communist rivals, Hankins noted that evangelicals like Graham don’t make a firm distinction between Old and New Testament citations. They see the Bible as a unity, and so when Graham cited the Old Testament, he saw it as a precursor to the New Testament, not an alternative text.

Graham’s evolution toward the New Testament, however, paralleled his acceptance of Catholics and more liberal Protestants. Graham got into trouble with fundamentalist Christians throughout his career when, starting in the late ’50s, he invited representatives of those two groups onto the platform with him to participate in his crusades.

“I think he did that much more intentionally the older he got,” Leonard said. “He came to see that there were layers of humanity and gospel.”

Graham increasingly identified with Jesus making “gospel exceptions” for people who crossed his path who were marginalized at the time, including women, those of other races and the disabled. “Maybe that move from anchor text suggests Graham came to terms with Jesus in ways that he hadn’t before,” Leonard said.

A video clip in the Museum of the Bible’s exhibition touts Graham’s solidarity with the civil rights movement, showing him telling a huge audience that Jesus was a Middle Eastern, and thus Asian, man, rather than a white person.

Along the way, there were missteps. Graham was infamously caught on tape telling President Nixon that Jews had too much control over the media, a statement of which he later repented, according to Hankins. And while Graham has been praised for integrating his crusades, he slid back sometimes and allowed some subsequent sermons to be segregated, Hankins said. Graham’s relationship with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was marked by an ambivalence about King’s methods, if not his goals.

“In some ways, he was pretty progressive for the time in terms of race, but he was still, as a white, Southern male, dragging his feet in some ways too,” said Schmidt.

The new exhibition, “Pilgrim Preacher: Billy Graham, the Bible, and the Challenges of the Modern World,” at the Museum of the Bible in Washington. Photo courtesy of MOTB

Graham’s increasing use of New Testament anchor texts doesn’t presume racial or religious tolerance. Like many Christian thinkers, Graham preached that the Old Testament covenant based on the Jewish law had been transcended by Jesus’ message of love, and that the Jews of Jesus’ day were too committed to the law, rather than God’s activity among them. “That’s a very strong message, and underneath it, particularly through the Gospel of John, is an abiding anti-Semitism,” said Hankins.

After Graham’s death at 99 last February, Rabbi A. James Rudin, former director of interfaith affairs at the American Jewish Committee (and a Religion News Service contributor), told RNS that Graham worked behind the scenes on many political causes that were important to Jews. Rudin met with Graham three times and corresponded with him between the meetings.

“I’m guessing that Graham softened some of that harshness about the role of the Jews as he got older, because he does open up dialogue with certain rabbinic communities,” Leonard said.

Still, even if the Hebrew Scriptures’ sometimes vengeful tone was tailor-made for denouncing communists, Graham might have heard a different view from his communications with rabbis. If Graham wanted to preach more love and less fire and brimstone, some might point out, he could have continued to draw from Jewish Scripture a third of the time without running out of material.