Painting of William Shakespeare.

(RNS) When the world commemorates the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death on April 23, he will be celebrated as the greatest writer in the English language.

The Bard’s linguistic power and beauty permeate his 38 plays and 154 sonnets, works unsurpassed for their keen insights and nuanced characters, including Hamlet, Lady Macbeth, King Lear, Ophelia, Othello and many others.

But one play, “The Merchant of Venice,” and one character, Shylock, have cast a shadow over Shakespeare for more than four centuries. At the center of the play, first performed in 1605, with its frothy romance, hints of homosexuality and cross-dressing, lurks the venal Shylock, the stereotypical Jewish moneylender.

READ: Rome’s Jewish catacombs to open to the public

The actual “Merchant” is the Christian Antonio, who defaults on a loan from Shylock and calls his Jewish creditor a dog and twice spits upon him.

Many historians believe it unlikely that Shakespeare ever met a Jew because King Edward I expelled Jews from Britain in 1290 and it was not until 1656 that they were allowed to return.

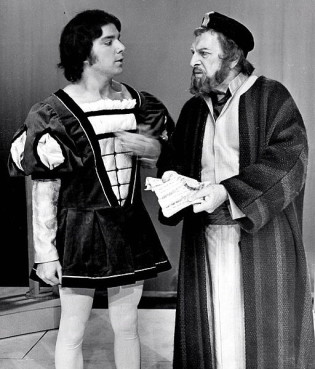

Alan Safier (Gratiano) and Morris Carnovsky (Shylock) in “The Merchant of Venice” in 1973.

Life in 16th-century Venice, the scene of the play, required Jews to live in a confined fetid area that gave the Italian word ghetto to the world. Jews were not allowed to travel after dark and were grudgingly tolerated because they performed a vital service: Christians in that era were forbidden to lend money at interest. But if Venice was to remain a a prosperous city-state, someone had to do it. That unpopular task fell to the Jews.

Shylock lends money to the “Merchant” with no interest, insisting instead on extracting a pound of Antonio’s flesh along with the repayment: a reference to the anti-Jewish blood libel canard. Shakespearean scholars debate whether Shylock truly wanted to commit such a grisly act.

The plot intensifies when Jessica, Shylock’s daughter, converts to Christianity, steals her father’s jewels and money and weds a Christian.

Seeking his pound of flesh, Shylock appeals to the Duke of Venice, but thanks to a series of legal gymnastics the Jewish “alien” loses his property and faces death for physically threatening Antonio’s life.

Shylock is presented a choice: Convert to Christianity or die. He chooses the baptismal font to save his life.

Scholars and actors have struggled to portray Shylock in a positive way to prove Shakespeare was not an anti-Semite. They cite Shylock’s famous lines of compassion and empathy:

I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us do we not bleed? If you tickle us do we not laugh? If you poison us do we not die? And if you wrong us shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that …

It is argued that Shylock’s noble speech, which frequently brings tears to an audience when contrasted to the disgusting behavior of Antonio and other Christians in the play, reveals Shakespeare’s humanity regarding Jews as well as his opposition to prejudice and bigotry. They believe Shakespeare demythologized the anti-Jewish stereotype of Shylock and made him into a sympathetic human being.

READ: Argentina’s ‘Dirty War’ survivors deserve access to Vatican archives (COMMENTARY)

English actor Charles Macklin as Shylock in Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice” at Covent Garden, London, 1767-68.

But critics point out that “Shylock” entered our lexicon long ago to describe the wicked traits supposedly inherent in Jews. They remind us that Nazi Germany had nearly 50 productions of “The Merchant of Venice” on stage, screen and radio between 1933 and 1939 to “prove” the vengeful nature of Jews and their parasitic greed.

“The Merchant of Venus” is artistically radioactive. For 400 years, Shylock’s toxic character has poisoned Christian-Jewish relations, inflicting pain and contributing to mass murder during the Holocaust. As a result, there are often calls to ban the teaching of “Merchant” in schools and to boycott performances on stage.

Ironically, in 2012 there were attempts to bar Habimah, Israel’s National Theater, from presenting a Hebrew-language version of “The Merchant of Venice” at London’s famous Globe Theatre. Critics of Israel, including recent Oscar-winning actor Mark Rylance, denounced Habimah for staging plays in the disputed West Bank. But Rylance’s group failed to block the Israeli performances in London.

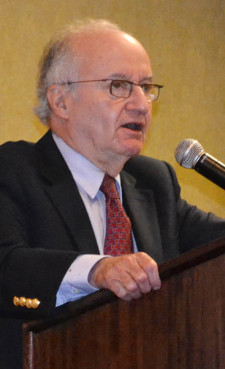

Rabbi A. James Rudin is the American Jewish Committee’s senior interreligious adviser. His latest book is “Pillar of Fire: The Biography of Rabbi Stephen S. Wise,” published by Texas Tech University Press. He can be reached at jamesrudin.com. RNS photo courtesy Rabbi Rudin

In his book “Shakespeare and the Jews,” Columbia University Professor James Shapiro wrote that “censoring the play is always more dangerous than staging it. The Merchant’s capacity to illuminate a culture is invariably compromised when those staging it flinch from presenting the play in its complex entirety.”

I agree with Shapiro. “Merchant” can provide a “teachable moment” if the play’s historical context is fairly presented. My suggestion? A note of caution before each performance and a panel discussion after the play ends.

(Rabbi A. James Rudin is the American Jewish Committee’s senior interreligious adviser. His latest book is “Pillar of Fire: The Biography of Rabbi Stephen S. Wise,” published by Texas Tech University Press. He can be reached at jamesrudin.com)