(RNS) — Twenty-five years ago this week, Doom, the original first-person shooter game, debuted.

And like millions of other Americans, my older brother played it often. My brother is seven years old than me, so since I was too young to really play the game, I’d sit beside him as he played. We’d insert the floppy disk into the computer tower and wait anxiously for it to load. I watched every move he made, filled with excitement.

I experienced a combination of terror and awe: gun in hand, destroying demonic monsters and those who guarded them anytime they came into our path.

It was one of the first times as a child I really considered the idea of monstrous demons or hellish places, because they had come to life on a computer screen. Even though I wasn’t physically playing Doom because I was so young, sitting next to my brother, watching him play, ushered us into another world. It was a world of good and evil, and we were there on a mission. Perhaps the experience also played into my later zeal for Christian salvation, especially when it came to the people I loved.

Doom fit with much of Christianity’s concept of hell, pictured by the descriptions of Dante’s “Divine Comedy”: layers of hell in which people are punished according to their mortal sins.

As Christians, we must be the ones figuratively holding the guns, destroying evil, all the while using our Bibles to save the lost. We must be the ones changing the world by eliminating the threat of an eternity in hell.

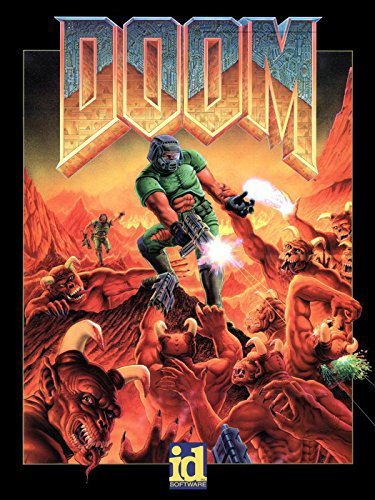

A poster from the original 1993 Doom. Image courtesy of Doom

In the world of Doom, my brother imagined himself a killer, and I imagined myself a killer, both with a holy mission to destroy evil.

I don’t play video games anymore, but my brother and I played for a long time throughout our adolescent and teenage years. The memory of these games still sticks with me, so much so that when I Googled a video of Doom, the exact same feelings I’d experienced as a young girl came rushing back: adrenaline mixed with high anxiety.

Psychiatrist Victoria Dunckley argues that video games can have a profound effect on those who play them.

“Playing video games mimics the kinds of sensory assaults humans are programmed to associate with danger,” she wrote in a Psychology Today piece titled “This is Your Child’s Brain on Video Games.” “When the brain senses danger, primitive survival mechanisms swiftly kick in to provide protection from harm.”

Playing Doom with my brother produced those same kinds of fight or flight responses, ones that later followed me into the church sanctuary every time I heard a pastor preach on the importance of saving the world from imminent hell.

Perhaps without realizing it, I imagined myself there with a gun, shooting down demons and those who guarded them, just in time for the apocalypse.

Later, I attended a musical camp called Armor, based on a passage in the Book of Ephesians that counsels Christians to put on the full armor of God. As campers, we considered ourselves warriors, ready to take down the enemy. That same language is taught often in the church, preached from the pulpit as a call to stand against the flames of hell.

“For our struggle is not against flesh and blood,” the author of Ephesians warns us, “but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms.”

So, we arm ourselves for battle.

If we truly believe in the threat of hell, we arm ourselves with God’s armor: truth, righteousness, peace and faith. But God’s armor — and God’s weapons — look very different from the kind of armor and weapons my character donned in Doom.

And perhaps that’s where we get confused in a physical world in which we are told to pay attention to the spiritual side of things.

Some of the myriad demons players attempted to destroy in order to advance levels in Doom, the original first-person shooter game. Screenshot

If we are not careful, we can begin to see other people as demons, especially those different from us — those who are other, like the immigrants on the other side of the wall, parents on Medicaid, our Jewish friends worshipping in a synagogue, young black men on the streets, people with disabilities, indigenous women fighting a pipeline, or those whose politics are not like ours.

That can lead to a kind of militarized Christianity — a spiritual version of Doom, where those outside the church are monsters. And we are the ones holding the gun, slaying demons and monsters for the sake of salvation.

We have seen where this kind of mindset within Christianity can lead. It inspired the Doctrine of Discovery that allowed colonizers to enter any land they deemed “unsaved” and take it for themselves, killing or conquering indigenous peoples in the process. We saw it in the building of a nation that demonized people of color. We see it today in a society that fears outsiders and those who don’t fit our version of the American dream.

Perhaps it’s time to put away childish things, like Doom.

Perhaps it’s time to put down our guns. Perhaps it’s time to give up the joy we find in fighting demons and to see those around us as neighbors — not threats.

Perhaps it’s time to see the world around us and all of creation as sacred.

Perhaps it’s time to learn from our mistakes and to proclaim that nonviolence is the best way forward for a future of lasting peace — before we really meet our doom.

(Kaitlin Curtice is a Potawatomi author and speaker. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)