Matters — not “mattered.”

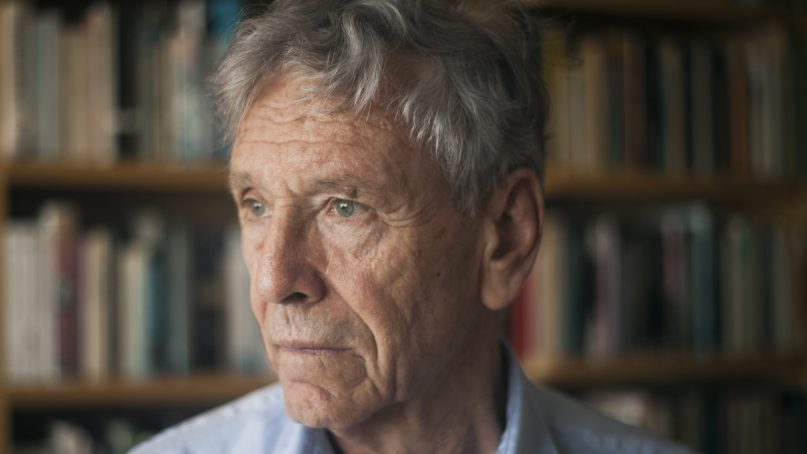

Amos Oz, one of Israel’s most important literary and intellectual figures, has died at the age of 79.

The eulogies, both written and spoken, will be free-flowing over the next few days. Amos will deserve all of them. The richness of his writing, the cunning of his vision, and his fierce love for the Jewish people, the land of Israel, and Judaism will all survive him.

Amos Oz created a body of literature that reflected the growth, struggles, joys, and angst of the growing Jewish State. His work appeared in 45 languages, in 47 countries, and received numerous international awards.

He loved Jewish literature, sacred or secular: “Ours is not a blood line, but a text line,” he wrote in Jews and Words, which he wrote with his daughter, Fania Oz-Salzberger.

He loved the Hebrew language; he noted that in 1900, there was no one who spoke Hebrew — today, over 10 million have that language on their lips.

He loved Israel — though he did not always like Israel. He was a noted leftist, and an early and vocal supporter of a two-state solution.

He recorded his struggles with Israel in ink, and some of those struggles made it into film, as well. His books gave birth to three movies: My Michael, Panther In The Basement (which inspired the sweet film, The Little Traitor), and his quintessential A Tale of Love and Darkness, which became the movie that starred Natalie Portman, and which chronicled life in pre-state Jerusalem, and Amos’s late mother’s struggle with depression.

And, he loved Judaism — in a quirky, instructive way.

Let me share with you three things that I learned from Amos Oz — things that have formed my outlook on what it means to be human, on Judaism, and on Israel itself.

First, what it means to be human.

Amos Oz was born Amos Klausner, and his father’s name was Yehuda Klausner.

In the 1940s, the Klausner family lived in Jerusalem. Mr. Klausner dreamed of becoming a best-selling author of scholarly books. He wanted to be like his friend, Israel Zarchi, whose books always sold out within a few days of their printing.

Yehuda Klausner would privately print his books, and he would take them to Achiasaph’s book store on King George Street in Jerusalem.

No one bought Mr. Klausner’s books. They just sat there in a pile, as their author became more depressed and more discouraged.

Finally, one day he got a call from the bookstore. All of his books had been sold! There had been an absolute run on his books! So much so, that a bookstore in Tel Aviv had put in an order as well!

Yehuda Klausner was elated, and this launched his modest career in scholarly writing.

A few years later, young Amos Oz was visiting Israel Zarchi in his cluttered apartment. Mr. Zarchi left the living room to get Amos a cup of hot cocoa. While Mr. Zarchi was in the kitchen, Amos was looking around, and he noticed something under the coffee table in the corner of the room.

It was a pile of his father’s books.

Israel Zarchi returned to the living room with the cup of cocoa. He saw Amos looking at the pile of his father’s books – and he held his index finger to his lips, as if to say: Please don’t say anything to your father.

You know what had happened. Israel Zarchi had secretly bought all of Klausner’s books.

And because of that, Yehuda Klausner had thought himself to be a minor commercial success, and because of that, he continued writing.

This is what Amos Oz has said about that incident:

“I have many close and dear friends. And yet, I am not sure that I could do for any of them what Israel Zarchi did for my father. Israel Zarchi was poor. He lived hand to mouth. At a certain moment, he must have said to himself, I can either buy some clothes that I need, or I can buy the three copies of Klausner’s book.’

“And he chose to buy my father’s book.”

I share this story because it is one of the most important illustrations that I know — of the cardinal Jewish value of chesed, selfless love.

Second, about Judaism.

Recall that Amos Oz was a secular Jew. He had no use for the synagogue or for worship. He saw religion as “archaic dust.”

But, he understood Judaism — in a deep and profound way. So much so, that he (perhaps unwittingly) offered the greatest definition of non-Orthodox Judaism that I have ever seen.

Amos Oz said this about Judaism: “Judaism is not a package deal. It is a heritage. And a heritage is something that you can play with. You can decide which part of the heritage you allocate to your living room, and which part goes to the attic or the basement. This is the legitimate right of every heir.”

Notice that Oz did not say that some parts of the heritage should wind up on the curb — though I would gladly leave those parts of the tradition that are anti-woman, anti-LGBTQ, and xenophobic on the street.

This means that (almost) everything Jewish is potentially useful to us.

Here is what I have come to learn: to be a Jew in the modern world is to see what should be in the living room, and what should be in the attic — and to not be surprised if you wind up re-arranging your furniture, and that you realize that a practice, an idea, a theology, a text that you once consigned to the attic actually has a place in your living room.

Finally, about Israel itself.

As I said, Oz was a leftist. He believed that when it came to the Palestinians, there was no way that Israel would “share a bed” with the Palestinians. We don’t need a wedding, he said; we need a divorce.

And yet, Oz was sober about the radical international left, and its illusions.

Here is how he responded to those who would dismantle the state of Israel, in In The Land of Israel:

I think that the nation-state is a tool, an instrument, that is necessary for a return to Zion, but I am not enamored of this instrument… I would be more than happy to live in a world composed of dozens of civilizations, each developing in accordance with its own internal rhythm, all cross-pollinating one another, without any one emerging as a nation-state: no flag, no emblem, no passport, no anthem. No nothing. Only spiritual civilizations tied somehow to their lands, without the tools of statehood and without the instruments of war.

But the Jewish people has already staged a long-running one-man show of that sort. The international audience sometimes applauded, sometimes threw stones, and occasionally slaughtered the actor. No one joined us; no one copied the model the Jews were forced to sustain for two thousand years, the model of a civilization without the “tools of statehood.” For me this drama ended with the murder of Europe’s Jews by Hitler.

This was Oz prose (!) at its best. It also forms my snarkiest (and, I think, succinct) refutation of anti-Zionism.

What a man. What a writer. What a voice.

And, if you really want to understand Israel, get this.

This is what Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had to say about Oz:

One of the greatest authors Israel had to offer. Oz made endless contributions to the renewal of Hebrew literature, with which he deftly and emotionally expressed essential aspects of Israeli life. Even though we had our differences, I deeply appreciated his additions to the Hebrew language and Israeli literature. His words and his writings will accompany us for many years to come. May he rest in peace.

“Even though we had our differences.”

That is Israel. And that was Oz.

He will surely be meeting God. And I can only hope that God is ready for him.