(RNS) — Our public discourse and politics feel like they are about to explode, don’t they?

With the fallout from President Donald Trump’s impeachment trial coinciding with the beginning of the 2020 election cycle, the outlook for the future looks positively frightening.

But looks can be deceiving. While Congress, the Twitterati and talking heads on cable news are at each other’s throats, the idea that the general public is polarized is, to say the least, overstated.

As I’ve highlighted in other contexts, Pew finds that a whopping 44% of Americans now identify as independent — the highest percentage in the 75 years Pew has been tracking this number. By contrast, Pew found that only 27% identify as Democrats and 26% as Republicans.

A major 2018 study of political affiliation in the U.S. titled “Hidden Tribes” found, as The New York Times put it, that most people “do not see their lives through a political lens, and when they have political views the views are far less rigid than those of the highly politically engaged, ideologically orthodox tribes.” Indeed, two-thirds of U.S. residents belong to what the study described as an “exhausted majority” whose members “share a sense of fatigue with our polarized national conversation, a willingness to be flexible in their political viewpoints.”

While the gatekeepers of our public discourse have a financial interest in keeping us anxious and antagonistic, the actual data show that dialogue across difference is possible. Even hopeful.

We must, however, take care in how we go about doing it.

Back in 2012 I published a piece with five suggestions for civil discourse, including humility, solidarity, avoiding binary thinking and dismissive name-calling and, finally, leading with what you are for, not what you are against.

Image by Gordon Johnson/Pixabay/Creative Commons

But I left out something really important, and I (re)discovered it again when I recently attended a conference put on by the Catholic lay group Focolare a couple weeks ago titled “A Hearth for the Human Family.”

The Focolare, which by statute must be led by a woman, came to be during the bombing of Trent, Italy, during World War II when the group’s founder, Chiara Lubich, and her friends huddled by the fire (Focolare means “hearth” in Italian) and opened the Bible to Jesus’ prayer “that all may be one.”

From then on, the Focolare would focus on unity, and especially on dialogue across difference, aimed at working toward that unity.

And, boy, has the group been successful. Focolare has brought a wide range of Catholic, Protestant, non-Christian and secular folks from all over the world into dialogue on many different kinds of issues, all the while keeping its members’ faith in Jesus, his blessed mother and the church at the forefront of their spiritual life.

The group’s outreach has been wide-ranging. In 1982, Lubich founded a School for Oriental Religions in the Philippines to foster understanding between Christians and followers of Hinduism, Buddhism and other Eastern religions. A long-standing relationship between Focolare and American Muslims began with her visit to the Malcolm Shabazz Mosque in Harlem in 1997.

A key aspect of Focolare’s passion for connecting was born out of the terrifying experience of a horrific war: the ethic of “Jesus forsaken,” which the group calls “the secret to unity.”

Unified love may be the tree of Christianity, but Lubich understood the roots to be the suffering of Jesus abandoned by the Father on the cross. Christ’s greatest act of love was to suffer greatly, and the Focolare, under her direction, would follow his example with a willingness to suffer toward the goal of unity.

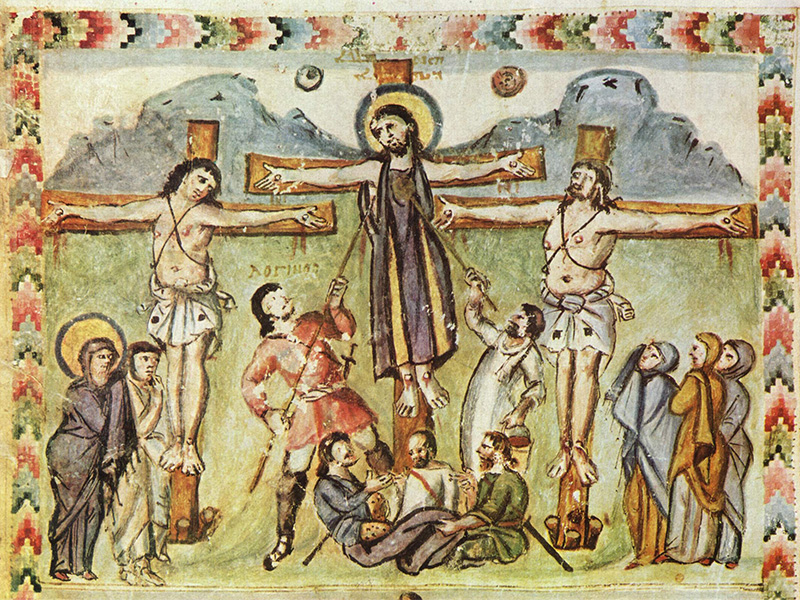

An early crucifixion depiction in an illuminated manuscript, from the Syriac Rabbula Gospels from 586 CE, shows both the sun and moon in the sky behind Christ. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

Significantly, the goal is not just to unite one’s own life to that of Jesus forsaken, but also to see him in our neighbor.

This notion is absolutely essential to how we think about dialogue, especially in an era defined by mass sorting into political and theological camps. Simply put, we must seek out the suffering of Jesus forsaken.

Not as an end in itself, of course. It is not masochism.

Rather, it comes from a realization that our attempts at dialogue across wide differences require us to be willing to suffer in the midst of the exchange.

This is a hard saying in our current moment. A reader might be thinking, “Could I really engage with a MAGA hat-wearing Trump supporter?” Or “Could I really engage with the reader at Drag Queen Story Hour?” The difficulties may be profound, but dialogue in these situations indeed means that we make ourselves, and our values, vulnerable in ways that produce profound anxiety.

The upside, though, is that embracing Jesus forsaken means getting outside ourselves to find the pain and abandonment in those with very different points of view. Acknowledging and learning more about that pain not only helps us better understand where people are coming from, it can blast open the protective shells so many of us created. What follows are the conditions for the exchange of genuine ideas.

Focusing on Jesus forsaken, perhaps counterintuitively, does not lead to more despair. Anyone who has met the Focolarini — thousands of lay people living a concentrated life in communities all over the world — knows them to be some of the most joyful people one has ever met.

Perhaps it is related to what Pope Francis described this week as the joy of one who “has the stigmata.” The joy that comes after God “tests our limits” and something we couldn’t have imagined comes from taking what we thought at first was an “unthinkable path.”

If there is to be true dialogue across difference during the 2020 election cycle, the Focolare reminds us that we should expect to suffer profoundly, and in ways for which we are not prepared. But we should also have the hopeful and joyful expectation that God’s grace will beautifully transform our encounters into something for which we are equally unprepared.

(Editor’s note: This piece originally stated that Lubich’s visit was in 2012. The correct year was 1997.)