(RNS) — It is 1969, and I am 15 years old.

I have a hero — a hero whose identity caused my parents never-ending grief.

Not Mickey Mantle. Not Mick Jagger. They would have preferred Mick Jagger.

No. I wanted to be Abbie Hoffman.

Imagine, then, my joy in watching “The Trial of the Chicago 7” on Netflix.

It was great to see the hero and role model of my adolescence again. Sacha Baron Cohen perfectly channeled the late Abbie Hoffman. This was no Borat nor Bruno. He looked like Abbie, and he even sounded like Abbie, capturing the radical leader’s Worcester, Massachusetts, accent.

“The Trial of the Chicago 7” omitted something that was central to the story – its Jewishness.

Or, sort of Jewish. Or, a certain kind of Jewish.

If you go through the dramatis personae, you will find that there is almost a minyan.

The defendants:

- Abbie Hoffman, of blessed memory: a product of the Reform Temple Emanuel in Worcester. There he received his Jewish education and became bar mitzvah. Abbie once claimed that the rabbi at his bar mitzvah ceremony was Rabbi Alexander M. Schindler, who would become the president of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations and one of the great American Jewish leaders of our time. Abbie’s timing was a bit off; he would have become bar mitzvah in 1949, some four years before Rabbi Schindler arrived in Worcester.

- Jerry Rubin, of blessed memory: a product of a major Reform synagogue in Cincinnati. He had also studied at Hebrew University.

- Lee Weiner: years after the trial, he would work for the Anti-Defamation League and was an activist for Soviet Jewry.

The defense team:

- William Kunstler, of blessed memory: one of the greatest radical lawyers of our time. His Jewish identity was, at best, spotty. Years ago, The New York Times reported that Kunstler had been raised as a Jew but no longer considered himself one.

- Leonard Weinglass, of blessed memory: Kunstler’s partner on the defense team. Jewish. No further information about his Jewish identity available.

The judge: Julius Hoffman, of blessed memory. Jewish.

Ah, yes: the tale of the two Hoffmans.

At one point, the judge made a point of emphasizing that the two men were not related — which prompted Abbie to cry out in fake anguish that his “father” was forsaking him.

Rabbi Arnold Jacob Wolf once brought Abbie H to dine at Chicago’s Standard Club. The two deliberately seated themselves near Julius H. That was Arnold.

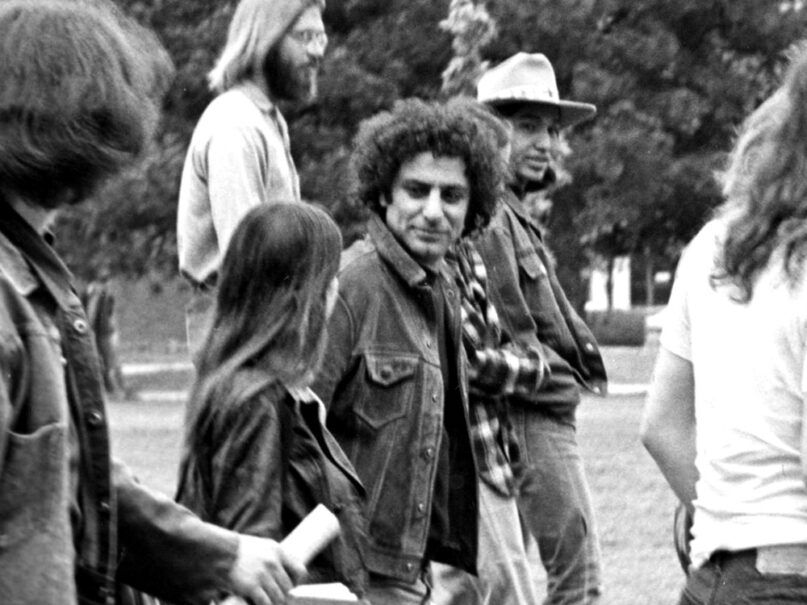

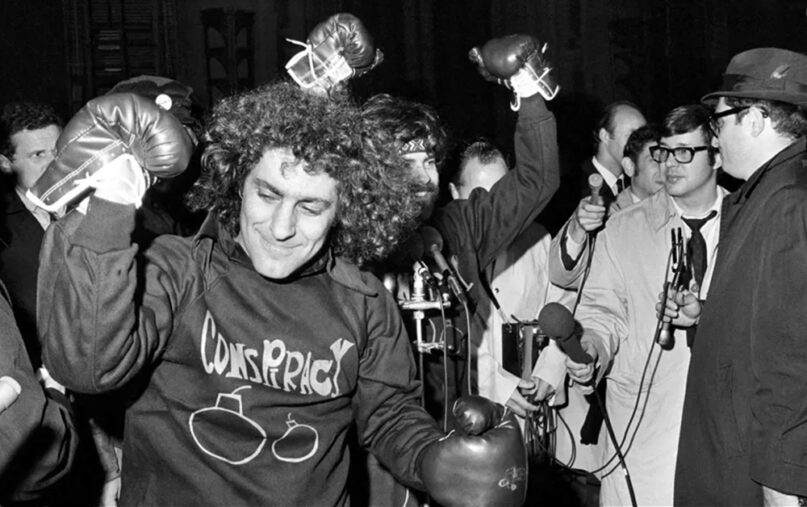

Abbie Hoffman, left, and Jerry Rubin wear boxing gloves as they meet newsmen in rainy Washington outside the Justice Department to publicize their cause on Oct. 27, 1969. They are among eight accused of conspiring to incite riots at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. (AP Photo/Harvey Georges)

The tale of the two Hoffmans was the real drama at the trial — and it was a great non-Jewish sociologist, John Murray Cuddihy, who wrote about it in his 1987 book “The Ordeal of Civility.”

Judge Hoffman fancied himself as an upper-class, assimilated “honorary” German Jew. That meant: cultured, refined.

Judge Hoffman told the radical Jewish activist Arthur Waskow to remove his kippah on the witness stand. Again: the proper Jew (Julius Hoffman) vs. the improper, “uncouth,” “too Jewish” Jew (Waskow).

At one point, Abbie Hoffman famously yelled at the judge: Shanda fur die goyim! — which he gleefully and inaccurately translated as “front man for the WASP power elite.” (The real translation is much too complex to accurately render here: “the way you are behaving is causing Jews to look shameful in front of gentiles.”) Both Abbie and Jerry Rubin delighted in equating Judge Hoffman to Hitler.

Abbie Hoffman was acting out another kind of Jewish identity — the deliberately countercultural, madly iconoclastic Jew. He and Rubin were clowns. The Youth International Party (the yippies) took great pleasure in creating mayhem. Abbie was in a direct line from the late comedian Lenny Bruce and the Marx Brothers. (In fact, they wanted to bring Groucho Marx as a defense witness!)

So, who better to play the madcap radical than Sacha Baron Cohen?

Judge Hoffman represented a different kind of Jewish identity — the Jew who represented the dominant culture. He was the Jew who wanted to fit into proper society and not draw too much attention to one’s Jewish identity.

But, there is another chapter to the Jewish story — the Jew as a serious radical.

A colleague of mine recalls that in 1970, he invited Rubin to speak at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Rubin’s native Cincinnati.

What were Rubin’s opening words to the rabbinical students and faculty?

“Long live Yasser Arafat!”

This was the version of radicalism that was (let me coin a term) “Che Guevara-ism.”

Oh, how we loved Che! How we loved our posters of him! How we loved our T-shirts with his likeness imprinted upon them! He is still revered as an icon in Cuba.

How we deftly remained willfully ignorant about the fact that Che was a mass murderer and a failed revolutionary.

The very radical left did not care about the violence that supported their causes. They even reveled in it. “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh; the NLF is gonna win!” we yelled at anti-Vietnam War rallies. They did, actually — and it was a bloodbath.

In 1974, I wrote:

“The radical Left has created a paradigm into which all history and ideas must fit in order to be valid. The acts of socialist governments, no matter how heinous, are instantly justified as being for the liberation of the people. Terror receives instant accreditation.

Evil becomes the exclusive domain of the capitalists. And, because the United States has been wrong in its foreign policy decisions in the past, it presumably stands to reason that its alliances will continue to be evil and self-serving.”

That turned out to be my farewell letter to the left. It was my farewell letter to Jerry and Abbie and my youthful naiveté.

I recognized that youth version of myself again on Netflix. I watched the scenes of the Chicago riots, and they gripped me.

I heard the cries: “The whole world is watching!”

By the way — it still is.

Vote.