(RNS) — Along with the crisp, cool air of fall arrives the Hindu festival that celebrates Hinduism’s goddess, Durga, in all her forms.

Some communities will celebrate it as Navratri, a Sanskrit word loosely translated as “nine nights.” In other communities, particularly those from India’s eastern state of West Bengal, it is the time for Durga Puja, or Durga worship time, when the goddess is believed to leave her heavenly abode to visit devotees. Both Navratri and Durga Puja will be celebrated by the South Asian diaspora across the United States, with Navratri beginning on Oct. 7 this year and Durga Puja on Oct. 11.

Navratri’s nine days celebrate Durga’s nine forms as she transforms from benevolent mother to Mother Kali, her fiercer side. In some legends, Durga actually gives birth to Kali (She Who Is Death) to defeat the demonic forces. But Durga herself is celebrated at this time as Mahishasura Mardini: the one who killed the unconquerable demon, Mahishasura.

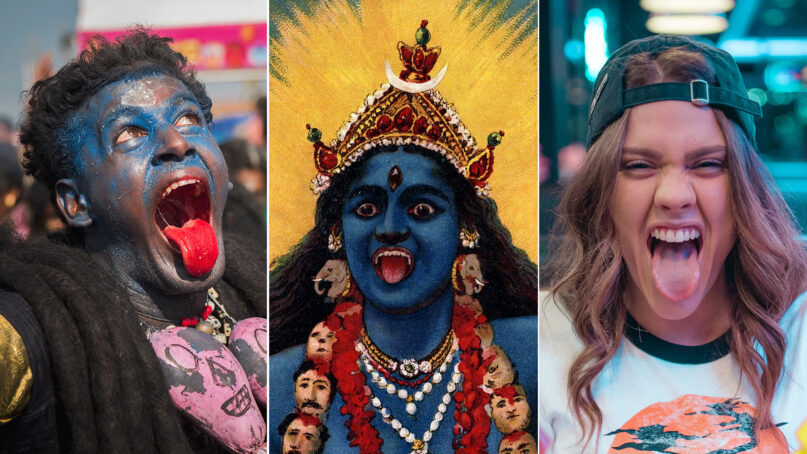

As Kali she is depicted as carrying a blood-splattered sword in one hand and the head of a demon in another. She wears a string of human heads around her neck and a girdle of human hands. Her blood-red tongue protrudes from her mouth, and her eyes are blazing. With her one foot placed on the thigh of her consort, Shiva, who lies in a supine state, and another on his chest, she has mystified scholars and given birth to numerous legends.

In Western portrayals, and larger feminist discourse, this image of Kali is held up to emphasize empowerment and wild sexuality. Taken out of her cultural, religious and philosophical context, however, many of her Western depictions make her quite unrecognizable to me.

In her essay “Kali’s New Frontiers,” scholar Rachel McDermott writes that in the Western interpretation, Kali has come to be viewed as a tantric goddess, with many of the rituals to her devoted to sex. McDermott describes how Kali is depicted on the web as a “Playboy centerfold.” In the early to mid 1990s, Tantra magazine used to publish a regular column of questions and answers on sex directed to Kali called “Dear Tantric Goddess.”

Kali has also been appropriated into many New Age rituals that depict her as “a patron of sexual fulfillment,” McDermott explained. McDermott has found scores of Kali worshipping groups in her research: Witches Web of Days, Temple of Kali, the “Daughters of Kali,” among others, that conduct exotic rituals, including animal sacrifices. In one such ritual, initiates are asked to jump into an inky cauldron to experience rebirth.

Photo by Sonika Agarwal/Unsplash/Creative Commons

Many more rituals related to Kali are touted on the internet. One blog offers advice on a yoga asana where one “takes a goddess squat” and lets out “several primal roars from the belly” to “invoke the energy of the Goddess.” Another suggests that Kali “can help you get in touch with your sexuality and ask for what you want from your partner because she doesn’t try to hide or conform. She expresses herself freely with no shame.”

One can find handbags, clothes, souvenirs, even boxer shorts or panties, all with an image of Kali emblazoned on them.

In all these rituals and paraphernalia, Kali is imagined as exotic, fierce, wild, sexual and destructive. It is a reminder of what Edward Said described in his 1978 book “Orientalism,” as the West’s consistent representation of the East as exotic and inferior. Another scholar, Hugh B. Urban, writes that this representation goes back to the broader “colonial morality” and “British attitudes towards sexuality and gender” in the 19th century, when Indian women were commonly imagined to be “excessively sexual, dark and seductive … ,” which, as he argues, is reflected in the “aggressively sexual image of Kali.”

Scholar Frédérique Apffel Marglin also writes about how Western understandings of female sexuality in the Hindu world have been strongly colored by cultural meanings from Western traditions. “All too often familiar meanings have been projected onto less familiar cultural facts. The Hindu world is complex,” she writes. Indeed, scholar McDermott asks in her essay, whether in the hands of her new interpreters Kali would become “unrecognizable to the culture from which she sprang.”

On my altar, I see Kali as Parvati, the form in which she undertook severe penance to marry Shiva. She is Sati, another avatar, who immolates herself when her father seeks to humiliate her consort. She is Durga, who fights the evil forces of the world. She is also the mother, who creates the god Ganesha out of her own body.

An Indian artisan stands among clay statues of Durga as they are being readied for the Durga Puja festival inside a workshop in Gauhati, India, on Sept. 20, 2018. (AP Photo/Anupam Nath)

Growing up, I saw Kali as a personal goddess of my mother. Her image, encrusted over the years with offerings of vermillion and sweets, nestled in an alcove in my mother’s kitchen.

RELATED: India’s Durga Puja celebrates divine feminine with modern takes on ancient ritual

During Navratri, this alcove would come alive as my mother incorporated the Hindu practice within her Jain tradition. She would also invite young girls from the neighborhood, as is the religious custom, to worship and offer food as though they were goddess embodiments. Watching my mother choosing her own personal goddess, defying tradition, was by itself empowering to me.

Today, Durga, in all her forms, accompanies me on my life’s journey through its joys and travails, much as she did for my mother. In gazing upon her, I’m also reminded at once of the innumerable stories, folklore and legends that have been part of my life. Perhaps there is a reason in India, the culture where she originated, that the goddess is celebrated not in her parts, but as a whole — one festival of nine days, recognizing her different forms.

My Navratri celebrations are simple and often without rituals or fasting. Much like my mother’s, it is a time of the year that reminds me of the energy of Durga or Kali, both around me, and also, as Indian philosophy says, within me. Her multiple manifestations seem to accept and love every side to me. And that is what is truly liberating.

(Kalpana Jain is a senior editor for religion and ethics at The Conversation. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)