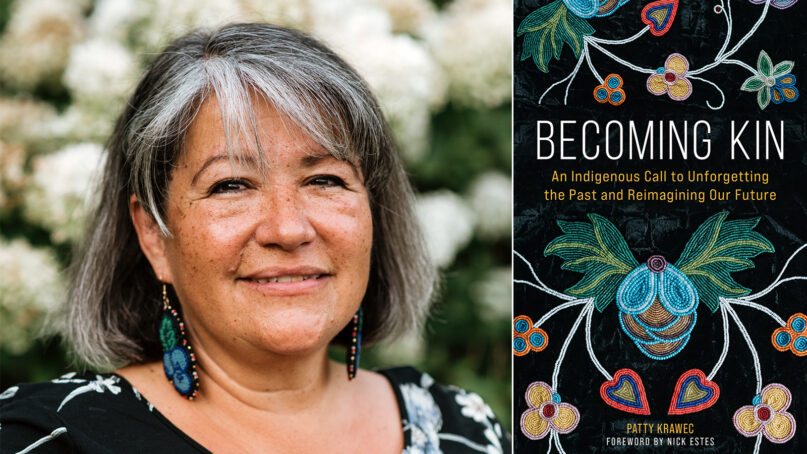

(RNS) — Patty Krawec, a writer and podcaster from Lac Seul First Nation in Canada, was thinking of all “the good Christians I grew up with” as she wrote her first book, “Becoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining Our Future.”

Krawec was raised by her mother, who is Ukrainian, in evangelical churches in the 1970s and ’80s. Later, as an adult, she reconnected with her father, who is Ojibwe, and began volunteering with different organizations to get outside her comfort zone after realizing her entire social circle was Christian.

These days, she said, “I’m finding more and more of the person I want to be within the Ojibwe belief system, which doesn’t require me necessarily to reject Christian ideas.”

Krawec is a member of Chippawa Presbyterian Church in Niagara Falls, Ontario, but she said she hesitates to call herself a Christian, wary of any assumptions that accompany the label.

RELATED: The pope’s apology tour has some conspicuous gaps — let’s start with Junipero Serra (COMMENTARY)

Still, she was thinking of Christians when she wrote “Becoming Kin,” released Tuesday (Sept. 27) — Christians who might be surprised, as she was, to learn there are good people doing good things outside of the church; to learn how much more there is they don’t know.

She was thinking of the history they’d been taught about what is now Canada and the United States and how they could rethink that from Indigenous and Black perspectives.

And she was thinking of how that new perspective on the past could impact the future.

“I think that we’re really in a moment where people are interested in hearing and questioning these things,” Krawec said.

“We’ve forgotten these things. And so we need to pull them forward again, and we need to think about them again and not pretend that they didn’t happen or that they happened differently, and not pretend that they don’t have long term consequences. If people can inherit the wealth of their families, then they can inherit the responsibilities, too.”

Krawec talked to Religion News Service about “Becoming Kin” and why rethinking — or “unforgetting,” as she calls it — history is important.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

How can rethinking the history in North America, perhaps particularly between white Christians and Indigenous peoples, lead to a better future?

What we can do is we can understand: OK, that displacement in the 1800s was really bad, but it’s still happening. So what can we do about it now? What can we do about the way Canadian and American mining companies behave overseas? This was something Sarah Augustine brings up in her book “The Land Is Not Empty” — why aren’t churches sending missions to the banks and to the mining companies? Residential schools aren’t even over.

These things aren’t over. They’re still happening. So how can churches learn from what they did in the past and do something different — and does it always have to be about evangelism? Can’t it just be about building a better world for us to live in?

RELATED: Potawatomi Christian author Kaitlin Curtice on finding herself and God in new book

You begin the book with creation stories. Why was that an important place to start?

Because that’s how we understand everything else about our world. Something that really struck me when I was learning about the Anishinaabe creation story was it follows a very similar trajectory to the one I had grown up learning, but when you get to the creation of man, there’s two very different lessons and there’s consequences from those lessons. In the Christian creation story, the way it was taught to me, man was the pinnacle of creation. And in the Ojibwe/Anishinaabe creation story, man was created last, the most needy of all creation. Everything else would get along fine without man, but man needs all these other things. Those are two very different ways of entering the world and entering into relationship with other things.

We’re in a moment right now like we were at the time of Reconstruction and the Gilded Age. That was a moment of possible change, and I think we’re in another one. That means the creation story is still being written — how the U.S. emerged. It’s a really good time to look at the stories we tell ourselves about how Canada and the U.S. came to be to see if we can get something better out of it that will lead us into better relationships.

You write, “What I know of the worldview of the Anishinaabe is not completely inconsistent with what Christianity could be.” Where do you see that resonance? How do you envision what Christianity could be?

The idea of a creator and a world in which we have relationship with not only other humans but other beings — the Bible talks about trees clapping their hands with joy and the stars singing. Those are not metaphors. They’re prophets seeing creation as being capable of emotion and having relationship with its creator. So I see that kind of possible congruence with how we saw the world.

When you read those stories from the Bible, there was none of this “deserving” and “undeserving poor” stuff. You helped the people who needed help. You protected the people who needed protecting. You welcomed the people who needed welcoming. And that’s very much an Anishinaabe worldview.

To me, I think a big part of the problem is the emphasis on proselytizing. The Indigenous communities I belong to in Toronto, and now in Niagara, don’t advertise and go door knocking: “Have you heard the good news of Nanabush?” People come to us. They come to the drum group. They come out to events. They’re very interested in joining with us and forming relationships with us, but we’re not out there proselytizing. So the church doesn’t need to do that either. They can just be good people living in good relationship with everyone around them, and people would want to join in relationship with them.

RELATED: On day of remembrance, churches confront their role in Indigenous boarding schools

You mention that when the unmarked graves of children were confirmed last summer near former residential schools for Indigenous children in Canada, many “settlers” wanted to rush to reconciliation. Is that a meaningful response, or what would be a better way to take action?

Really, if anybody had been paying attention when the Truth and Reconciliation Report had come out five, six years before that, there’s a whole section on those graves. One of the asks was for funding to look for them. It really wasn’t a surprise, but it still was because people weren’t paying attention. And so then you feel bad, and you want to fix it, and that’s a normal, laudable human reaction to see something terrible and want to take action, want to do something about it.

What I did was when my inbox flooded with messages about, “I feel terrible. What can I do?” was I gave people reading lists. Educate yourself. Participate in this program. Learn something. It’s really sending people away to do their own work. Then come back to me when you’ve got good questions, when you want clarification on things that you’ve taken the trouble to educate yourself on.

What happened at residential schools was the result of forcing people to comply with policies that benefited a certain part of the population over others. It was the result of secrets, hiding the abuses of power. So look at your own organization. Where are you protecting the organization?

You write, “There’s work to be done long before we sit down together.” What does that work look like for white Christians? For Indigenous peoples?

For Indigenous peoples, it’s about getting the colonization out of our heads. It’s about returning to our ways of understanding the world. And there are a lot of those internal things happening. There’s a lot more ceremony available than what used to be.

White Christians as a collective are really going to have to think about their landholding and what does it mean to be preaching Sunday after Sunday about grace and reconciliation and Jesus giving up everything to become human, leaving heaven and coming to earth, and you’re doing it on stolen land?

Once you start picking up those threads, you can’t stop, and it shifts how you read and how you hear everything. And I think that’s really important because the church is always evolving. The church as it exists now is not the church that existed 2,000 years ago, and there is no pure, original church that Christians should be trying to get back to. They should be looking at the text: How do we live now as a church in this world? What does it mean to be in relationship with Indigenous people? Do we even know who the tribes are in our area? What does our charity look like? Are we donating to things that are geared toward proselytizing? Or are we handing over money they can use for language revitalization because that’s something we took from them?

RELATED: Churches return land to Indigenous groups as part of #LandBack movement