CHICAGO (RNS) — Worshippers at a prayer service for truth and reconciliation late last month at St. Benedict Catholic Parish in Chicago’s North Center neighborhood prayed in English and in Ojibwe.

RELATED: Uncovering boarding school history makes for monumental task

They prayed to the four directions, the smoke from a smoldering bundle of sage curling skyward in the church’s sanctuary. They prayed as each person made their way down the church’s center aisle to leave a pinch of tobacco — one of the four sacred medicines in many Native American cultures — in a shared bowl to be burned.

They prayed for healing, for forgiveness and for their eyes to be opened to injustices committed against Indigenous peoples by what was known as the federal Indian boarding school system in the United States.

“It’s important because Native people can’t heal if nobody knows the truth,” said Jody Roy, director of the St. Kateri Center, housed at St. Benedict Parish.

Roy, who is Ojibwe, led the prayer to the four directions and helped the parish plan the service to make sure it would be culturally appropriate and accomplish “some kind of justice,” she said.

Parish leadership had asked her what they could do after she spoke with St. Benedict’s Pathways Toward Peace group earlier this year about the boarding schools, which separated thousands of children from their families and cultures in the 19th and 20th centuries.

She had shared stories with the group about how the legacy of those schools still impacts members of the St. Kateri Center community, which aims to preserve the spiritual practices and traditional cultures of Indigenous peoples within the Catholic Church.

Attendees participate in a tobacco burning ceremony during the Prayer Service for Truth and Reconciliation, Sunday, Aug. 29, 2021, at St. Benedict Parish in Chicago. RNS photo by Emily McFarlan Miller

“It really needs to be told — the truth, and not like a dusting, (but) the whole truth, the dark truth that there was physical, mental and sexual abuse that happened. And it can’t be a one-and-done thing. This is not something that we can just say, ‘Oh, we did it. We acknowledged it. We had a prayer service. We’re done. Let’s move on,’” Roy said.

Before her presentation, the priest and parishioners had been “oblivious,” she said. Now, they’ve committed to doing something each year to create awareness about the boarding schools.

Across the United States, churches of all denominations are reckoning with the role they played in the country’s boarding school system for Indigenous children.

Several U.S. mainline denominations — including the Episcopal Church, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the United Methodist Church — encouraged their members to observe a day of remembrance Thursday (Sept. 30) by wearing orange, learning about residential and boarding schools in Canada and the U.S., honoring survivors and remembering those who never came home from school.

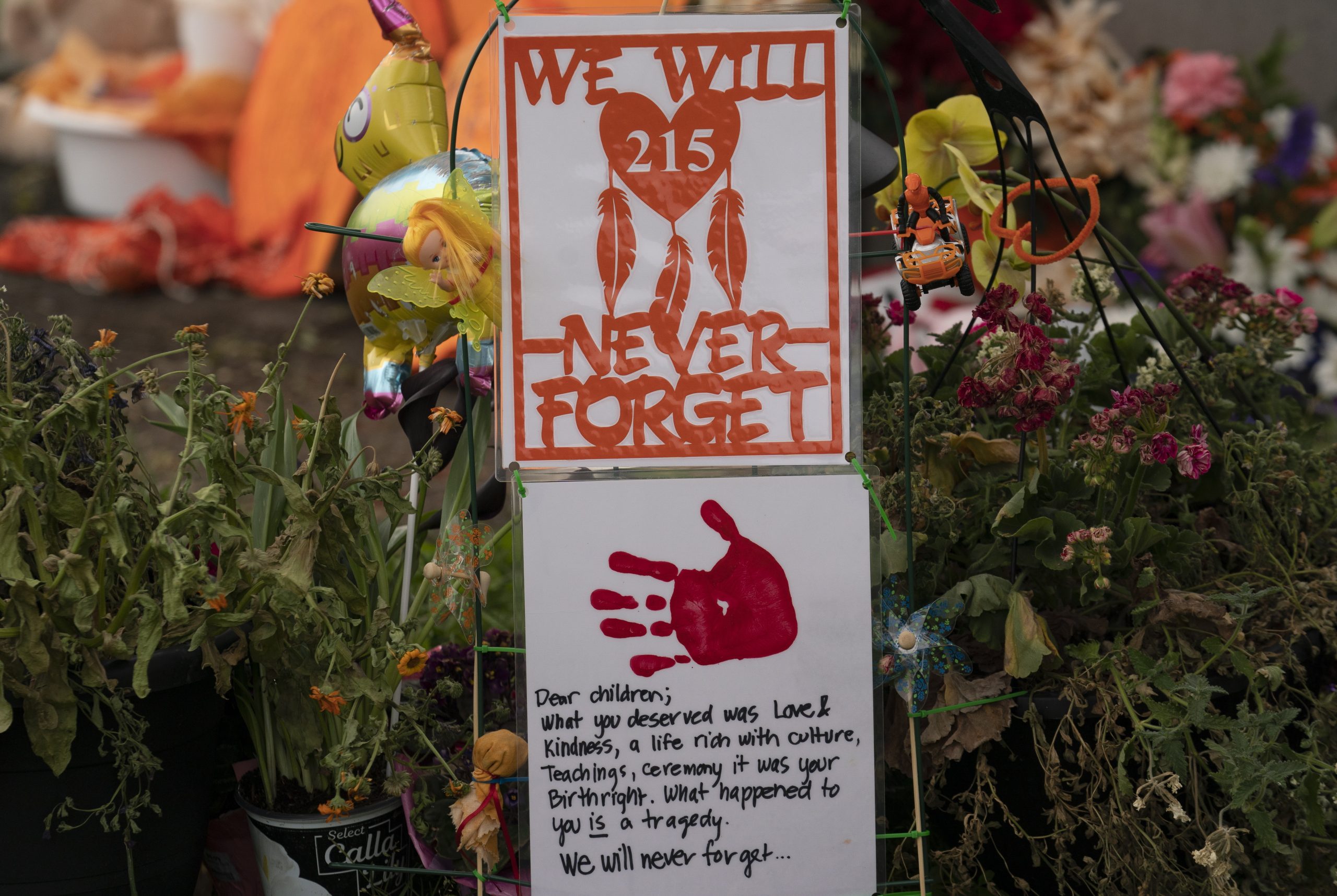

A memorial is seen outside the former Residential School in Kamloops, British Columbia, Sunday, June, 13, 2021. The remains of 215 children were discovered buried near the former Kamloops Indian Residential School earlier in June. (Jonathan Hayward/The Canadian Press via AP)

The day coincides with Canada’s first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and the Indigenous-led Orange Shirt Day. Wearing orange has become a symbol of solidarity and remembrance since one former residential school student shared that her orange shirt was taken from her when she arrived at school.

Started in 2008 and concluding in 2015, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission aimed to confront the country’s history of residential schools.

United Methodist Church leaders said this week that the second-largest Protestant denomination in the U.S. is working to identify boarding schools its predecessor churches may have been involved in as the country launches its own Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to investigate the loss of life at such schools and their lasting consequences.

Those investigations have been prompted by confirmations earlier this year that the remains of more than 1,000 Indigenous children are buried in unmarked graves near residential schools in Canada — and the U.S. had twice as many boarding schools as its northern neighbor.

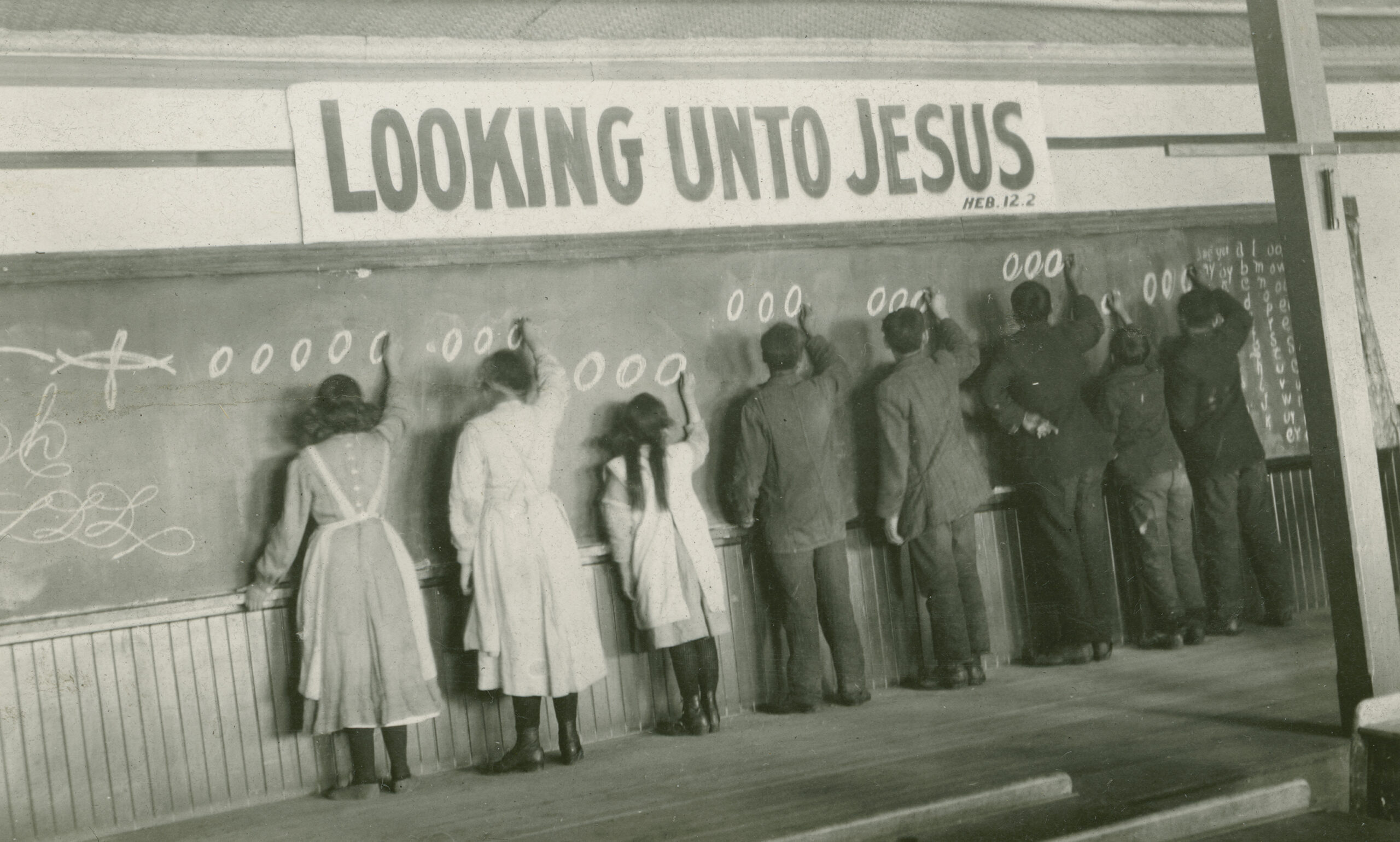

In this 1910s photo provided by the United Church of Canada Archives, students write on a chalkboard at the Red Deer Indian Industrial School in Alberta. In Canada, where more than 150,000 Indigenous children attended residential schools over more than a century, a National Truth and Reconciliation Commission identified 3,201 deaths amid poor conditions. (United Church of Canada Archives via AP)

The Minneapolis-based National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition has identified 367 boarding schools across the U.S., including 156 associated with the Catholic Church and various Protestant denominations. The coalition estimates that hundreds of thousands of Native American children attended those schools between 1869 and the 1960s.

While authorized and primarily funded by the U.S. government, many boarding schools were sponsored or operated by religious organizations, the United Methodist Church acknowledged this week.

“We know the names and locations of a number of Methodist-related Native American boarding schools and efforts are underway to identify as many such institutions as may have existed,” according to a written statement signed by United Methodist leaders.

“We need to better understand our complicity in this form of cultural genocide and to bring the boarding schools more clearly into focus in our expression of repentance for the inhumane treatment to which the church and its members subjected Indigenous people in the past.”

Episcopal and Presbyterian leaders have confirmed their denominations were associated with boarding schools, too, though their records are incomplete and research is ongoing.

Meanwhile, U.S. Catholic bishops have pledged their support for the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. Their counterparts in Canada also apologized this week for the Catholic Church’s participation in the country’s residential school system, acknowledging “the grave abuses that were committed by some members of our Catholic community; physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, cultural, and sexual.”

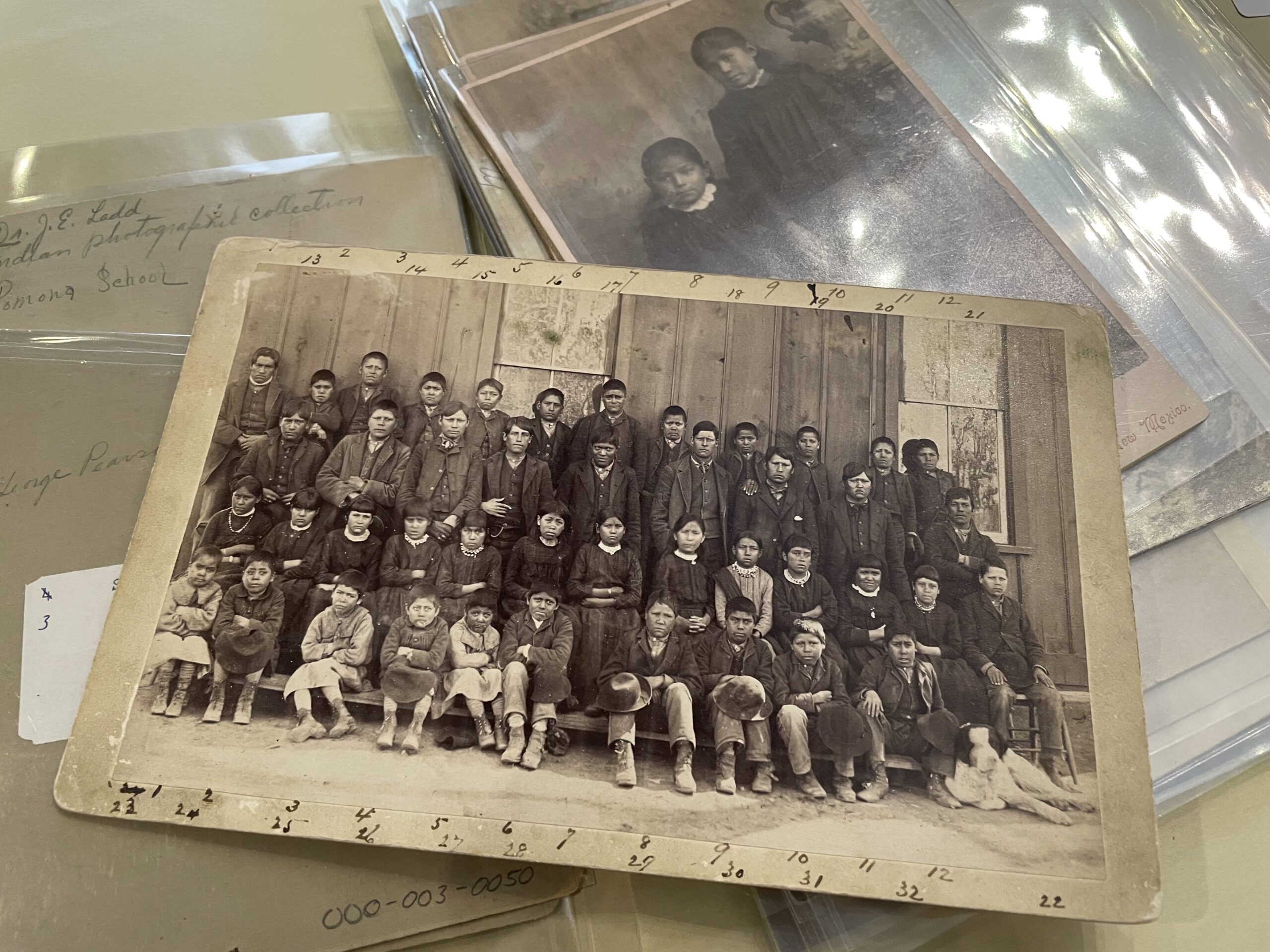

This July 8, 2021 image of a photograph archived at the Center for Southwest Research at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, New Mexico, shows a group of Indigenous students who attended the Ramona Industrial School in Santa Fe. The late 19th century image is among many in the Horatio Oliver Ladd Photograph Collection that are related to the boarding school. (AP Photo/Susan Montoya Bryan)

For many denominations, these investigations are seen as a necessary action following their repentance for the Doctrine of Discovery, the theological justification that allowed the discovery and domination by European Christians of lands already inhabited by Indigenous peoples. The United Methodist Church, Episcopal Church, Presbyterian Church (USA), Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, Evangelical Covenant Church, Unitarian Universalist Association, United Church of Christ, Community of Christ, World Council of Churches and a number of Religious Society of Friends (Quaker) meetings all have officially repudiated the doctrine in recent years.

“It wasn’t until recently, with the conversations around the repudiation of the Doctrine of Discovery, that denominations even began thinking about how they were implicated in these boarding schools, including in the Catholic Church,” said Vance Blackfox, desk director for American Indian Alaska Native Tribal Nations at the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

Blackfox, who is Cherokee and began his role at the denomination in the last month, said he plans to encourage ELCA synods and congregations to research what schools they may have supported. At least two Lutheran schools were funded by the U.S. government under its boarding school policy, and other boarding schools were run by Lutheran denominations predating the ELCA, he said.

He believes bringing that truth to light can bring healing, not only for Indigenous peoples, but also for white people, whose ancestors created the boarding schools and other assimilation measures. Such revelations can lead to policies and resources that assist with the growth and well-being of Indigenous peoples, he said.

“The truth does lead to healing,” Blackfox said.

That work is underway at Red Cloud Indian School, a former Jesuit-run boarding school on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

Maka Black Elk at the Red Cloud Indian School campus on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Photo by Marcus Fast Wolf

Maka Black Elk, who is Oglala Lakota, graduated from Red Cloud High School in 2005. His parents and great-grandparents attended when it was a boarding school in the years between its founding in 1888 and 1980.

Now Black Elk, who recently received the 2021 Distinguished Catholic Leadership Award from the Foundations and Donors Interested in Catholic Activities, or FADICA, serves as the school’s first executive director of truth and healing.

Black Elk grew up in the community with a mother who was deeply traditional and a father who had been a Benedictine monk, attending traditional sun dances every summer and Catholic Mass every Sunday. He recognizes Christians participated in the erasure of Indigenous cultures, including his own — but he also recognizes that behavior is “antithetical to the Gospel,” he said.

“People ask me, ‘How can you be Native and Catholic?’” he said.

“My pushback is, ‘How is anyone part of the Catholic Church, given its history?’ … It’s a reckoning that all Catholics have to have, particularly in the Americas. They need to reckon with what does it mean to be a part of a church that used to believe this and feel this way and do these things to really minimize and diminish and make feel less human a whole group of other people, given what we supposedly believe?”

Red Cloud’s truth and healing process began when its new president realized what the people in the community have known for years — “that there is a great tension in the history of this institution as a boarding school, and that tension still extends to this place remaining Catholic today,” Black Elk said.

Some community members who attended the school in the 1980s — after it abandoned assimilative measures and embraced Lakota language and culture — have fond memories of the experience. Others appreciate the school’s emphasis on preparing students for college. Still others see the school’s past and the fact that it remains Catholic as “repulsive” or a “product of that colonial history,” he said.

All are true at the same time, he said.

Since Black Elk was hired as executive director of truth and healing last year, he said, Red Cloud has initiated a four-stage process outlined by Hunkpapa/Oglala Lakota scholar Maria Yellow Horse Braveheart: confrontation (or truth-telling), understanding, healing and transformation.

Now in its truth-telling phase, the school plans to provide platforms for boarding school survivors to share their stories in whatever way is most comfortable for them, according to the director. It plans to search the school’s records, archived at Marquette University in Milwaukee, and make them accessible.

The school also plans to bring in the same ground-penetrating radar that was used to confirm that children’s remains were buried at residential schools in Canada, which Black Elk said has been well known to Indigenous peoples — it’s part of “our family history” — but caught many others by surprise.

RELATED: Denominations repent for Native American land grabs

And for those churches and denominations just beginning the work of truth and healing, the first phase is the hardest, Black Elk said. It’s accepting history without defending it.

“When it comes to our work moving forward here at Red Cloud, we’ve got a long way to go,” he said. “We may be further ahead than any other Catholic institution that has the history like we do, but we’re still so far behind in terms of the grand process.”