(RNS) — Potawatomi Christian author and speaker Kaitlin Curtice did not write her latest book with the intention that it would be read during a pandemic, but she has been surprised by the ways “Native: Identity, Belonging and Rediscovering God” speaks to this moment in history.

The book, released Tuesday (May 5), is structured around another disaster — the Potawatomi flood story — and the theme of starting over again afterward.

“Today, with this global pandemic, we are sort of asking what life will look like on the other side, how we can begin again,” Curtice said.

“So, in ways I never could have planned, this book is just what we need right now. We aren’t in a literal flood, but we are definitely in a world that is reeling and tired and we need to ask what beginning again might look like.”

RELATED: Looking to an Indigenous flood story for lessons on grieving during the pandemic

In “Native,” Curtice describes her journey of finding herself and finding God, of connecting with her Potawatomi identity, reckoning with the church’s historic treatment of indigenous people and other marginalized groups and the impact that has had on her Christian faith as a former worship leader.

She hopes sharing her own story will help readers examine their life stories, she said.

“Even though this is a book that covers a lot of difficult topics, I want it to be a book that is considered an invitation to those conversations. I want people to read it and be fueled to continue learning from Indigenous peoples, from those that are on the margins, from those that haven’t been listened to,” she said.

Curtice answered questions via email from Religion News Service about her new book, why it’s important for readers to understand who and where they come from and what gives her hope.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why was it important for you to share your personal story of connecting with your identity as a Potawatomi woman and rediscovering God?

These are the stories that are not often told, and because I speak to predominantly Christian audiences, I felt it was important to share that identity is a complicated, layered thing, and that these conversations are hard but necessary. I wanted to share my story to give other people room to examine their own ideas of God, their own identities.

For Indigenous people who read the book, a lot of us are asking questions about the Christianity we may have grown up with, if it’s possible to exist in these spaces. And I don’t have an answer necessarily, I’m still on this journey of asking as well. But I hope my experiences help them feel less alone.

RELATED: Kaitlin Curtice talks about ‘everyday glory’ and her Native American heritage

Why did you decide to build your narrative around the Potawatomi flood story?

The flood story is so powerful, this idea of beginning again, of asking what life will look like on the other side of grief. It’s a story about community and hope, and those are all themes that are really important in my life as well.

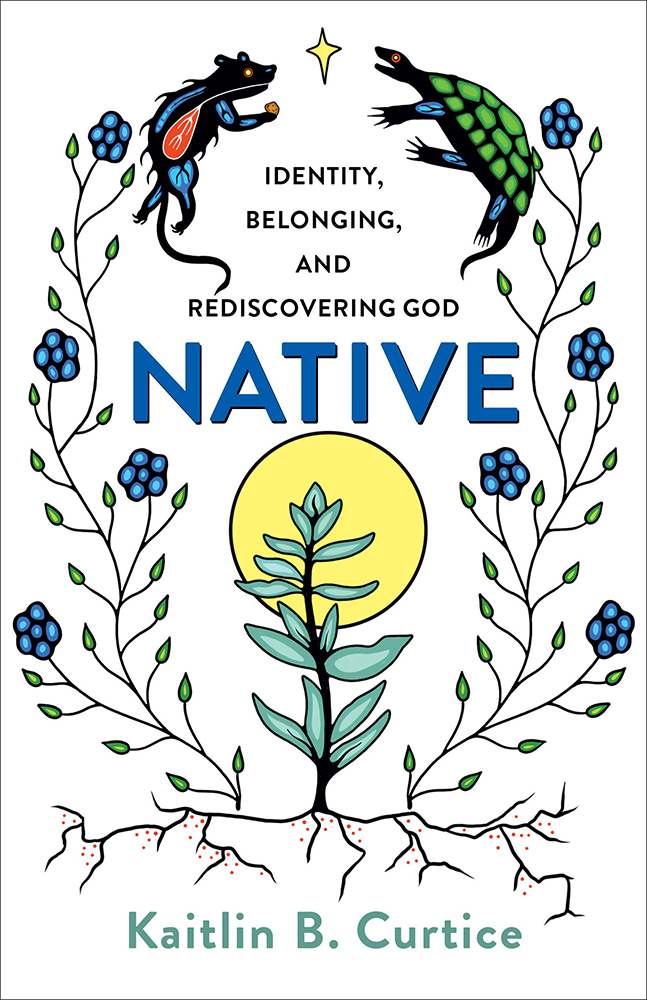

Can you talk about the art for your book cover and throughout the book? I know this was something that was important to you.

“Native: Identity, Belonging, and Rediscovering God” by Kaitlin B. Curtice. Courtesy image

The cover was designed by Indigenous artist Chief Lady Bird. She designed my first tattoo, which I share about in the book, and when I got that tattoo a few years ago I had this dream that one day she’d design my book cover. And now she has! The Muskrat and Turtle are on the front, both important characters in the flood story, and the sage plant growing up from the bottom represents our sacred medicine.

I could not have asked for a more beautiful cover, fully representative of everything I tried to pull together in this book. I’m so grateful.

You write in the book, “We must begin somewhere, and learning our own story is a great place to start.” What are some practical ways you might suggest readers start to learn their own stories, and what do you hope will come from that?

I don’t think I truly began to understand my own story until I learned to name my trauma and my truth. I would encourage people to begin there, to be honest about where or who they come from.

What makes us who we are, and who do we want to be now? EE Cummings has this quote, “It takes courage to grow up and become who you really are.” That’s the task ahead of us in adulthood, asking who we really are, wrestling with the hard questions, being honest with the whole picture.

You ask the question, “I am a descendent of Potawatomi people and European people, a descendent of both oppressed and oppressor. I come from ancestors who were both colonized and the colonizers. So how do I reckon with this?” How would you answer that question?

My answer to this question lies in the work of decolonizing, of giving voice to the parts of me that have been silenced by whiteness while also being aware of the privilege I carry every day. It is my responsibility to listen to Black and Brown Indigenous peoples, to understand that the white privilege I carry means I need to pay attention, or as I say in the book, “keep watch” over my own life and my own story. I need to take an active role in speaking the truth, and I hope that through this book and whatever books I write in the future, I am doing that.

RELATED: Potawatomi Christian chapel speaker Kaitlin Curtice draws ire of Baylor student group

How has connecting with your identity as a Potawatomi woman impacted your faith as a Christian?

It has given me the courage to let go of the toxic things I’ve inherited from Christianity, and it has widened my understanding of what it means to be a person who loves others well.

As I say in the book, Christianity is a journey, and I don’t know where I’ll be on that journey today or tomorrow, a few years from now. I know that listening to the voice that has been silenced in me for so long will only help me understand the Jesus that liberates and stands against empire.

RELATED: What would Rachel Held Evans do? Late author’s voice lives on through those she championed

You write about how “America is stepping into the light of calling out white supremacy for what it is,” specifically in politics, noting how the first Indigenous women were elected to Congress in 2018. Do you see a similar shift in the church in America?

Yes and no. Sometimes I have no hope that there is any shift at all, and that the people who are protesting in the streets right now because they are angry about staying home during a pandemic will always have control of this nation.

But I see shifts in so many people I’ve met of all ages who are trying to ask hard questions and tell the truth. This colonized version of Christianity we’ve inherited is not easy to root out, and I’m not sure if it will happen. I am grateful for the people I’ve seen doing it long before I even was, who will continue to do the work. They give me hope.