(RNS) — When Susannah Griffith first sat down to write a book about forgiveness in 2022, she was in the midst of finalizing her divorce.

Urged by church leaders to forgive her spouse for years of abuse, Griffith, an independent scholar and minister with a Ph.D. from Vanderbilt University, decided to examine the subject herself.

“I came to realize that forgiveness actually looked very different from what I had been taught,” Griffith told Religion News Service in a recent phone call. “I felt very strongly that forgiving my spouse looks like not being married to him anymore.”

Her writing on forgiveness has come, at times, at great personal cost. In 2023, she said, she felt pressured to resign from the Mennonite seminary she worked for after publishing an article in Anabaptist World titled “When peace theology is violent,” calling the community’s urging to stay in her marriage “emotional torture.”

“The fact that it was so offensive for me to talk publicly about my experiences within the Mennonite community, to me it was all the more important for survivors that I speak up,” said Griffith. “I believe that people are dying because they are being pressured by their communities to stay in abusive relationships.”

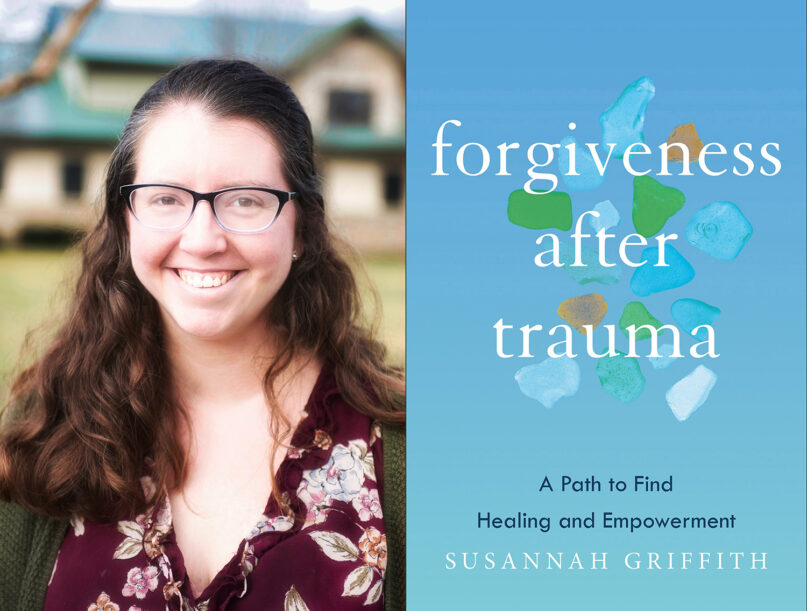

Griffith’s completed book, “Forgiveness After Trauma: A Path to Find Healing and Empowerment,” was released Tuesday (March 26). RNS spoke to Griffith about anger, reconciliation and biblical forgiveness. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What myths about biblical forgiveness do you mean to debunk?

One of them is that forgiveness means we can’t seek justice, ask for accountability or be angry. Biblical forgiveness is broad enough that it allows us to be authentic about the reality we experienced. To arrive at a place of genuine forgiveness, we need to have the space to be angry and seek justice. If we spiritually bypass those things, we’re not going to be forgiving. We’re just putting a BandAid on a much deeper wound.

What does Scripture say about forgiveness by a person in power versus forgiveness by a person who is vulnerable?

The stories Jesus uses to illustrate forgiveness have to do with somebody with a lot of power extending forgiveness to somebody who doesn’t. If you’ve got a lot of money, you don’t need to squeeze the person who’s less prosperous for the little debt they owe you. Those who have a lot of power are expected to forgive those who don’t. So it’s a total misapplication to use these passages against survivors of abuse, who are controlled by somebody more powerful.

You point in the book to Jesus’ teaching about retaining sins as well as forgiving.

He tells his disciples, if you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven, if you retain the sins of any, they are retained. The second part of that teaching normally gets forgotten. Retaining sins, continuing to hold someone responsible for their actions, is something we don’t see a lot of in Christian culture. When a leader commits a sexual indiscretion, there can be a lot of pressure to reincorporate him into the community. To make Christian culture safer for survivors, we need to think what this means for rejecting abuser participation in certain Christian spaces.

How have you come to define biblical forgiveness?

When I boil it down, biblical forgiveness means relinquishing the justified right we might have towards vengeance or retribution, recognizing that we’re held within God’s justice and mercy. We’re not responsible for achieving what would ultimately be the just outcome. We can trust in God’s justice and mercy to do whatever needs to be done to restore creation.

That doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t pursue legal action, justice or accountability, but at the end of the day, our legal systems will fail us. Our resolutions won’t provide us with the emotional closure that we feel we need. We can trust that God’s justice and mercy are there for us, and will take care of whatever needs to be done.

What advice do you have for churches responding to abuse allegations?

I don’t think talking about forgiveness is ever the first line of response. Safety is always more important than forgiveness. We can’t even have the conversation about forgiveness if we’re not safe.

Churches should realize that the actual abuse may be even more, not less, than what they’re hearing, and realize that whatever they say or do may have real implications for someone’s safety and life. When I was going through domestic violence, I often felt my safety and emotional health were less important than this abstract concept of forgiveness, which to church leaders meant staying in an abusive marriage. That had long and devastating consequences for me.

Why is it important to not ignore the anger God expresses in the Bible?

For many Christians, especially maybe progressive Christians, we’re uncomfortable with the idea of God being angry. But we’re also uncomfortable with anger in human relationships, too. This is especially true of women who have been socialized to mask anger with a smile. Forgiveness requires that we’re dealing in the reality of what has happened, and oftentimes the reality of what has happened should make us angry. Anger is part of the way that we reflect the Imago Dei. When we have anger at injustice, we’re becoming more like God.

You say the Gospel of Matthew’s 18th chapter, encouraging people to confront a brother or sister who sinned against you alone, should not be used in cases of abuse.

Jesus is addressing people who are mostly equal. In Greek, the word is adelphos, which means brothers. But abuse happens when some people are in positions of power over others. I don’t think it’s a good application of Matthew to ask people in intimate partner relationships of violence to deal with this privately, and then shame them for coming forward. It puts victims in danger.

You write that you think Christians have vastly overstated the relationship between forgiveness and reconciliation. How so?

Forgiveness and reconciliation are often conflated, but the Bible talks about reconciliation as primarily the work of God, which eschatologically heals all creation. Humans can be agents for that reconciliation, but the burden is never placed exclusively on people, and it’s never talked about exclusively in terms of an institution like marriage. I don’t have to still be in my marriage for God’s reconciliation of the world to be carried out. We need to really expand our vision of reconciliation.

You write that rebirth is at the heart of what forgiveness means for you now. What has that looked like?

I began to feel a sense of rebirth through my divorce, which was my way of forgiving my kids’ dad by releasing him from the wrong he had done. That was only possible by fundamentally changing our relationship. Rebirth looks for me like being able to choose the relationships that I’m part of, and not feeling forced to be in a marriage for fear of the consequences if I try to leave.

It looks like healing from trauma, which was only possible through putting space between myself and the relationship in which those terrible things happened. It looks like exploring what a healthy relationship looks like, as I have now remarried. Together we’re exploring co-parenting our kids alongside our kids’ dad.