Please note there is graphic imagery in this article.

(RNS) — As Thunderclap Newman would have put it: “There’s something in the air.”

For Jews, that “something” is the pandemic of antisemitism — a pandemic that has gotten so palpable that it earned itself a frontpage article in the Sunday New York Times.

Antisemitism has a starring role in two hot Broadway plays — “Leopoldstadt,” by Tom Stoppard, and the revival of the musical “Parade,” with a dramatization by Alfred Uhry and music by Jason Robert Brown, starring Ben Platt.

“Parade” is a tragedy — the story of Leo Frank, the first American Jew to die in antisemitic violence and the only white person in America to be the victim of lynching.

Several years ago, I spent an evening with a group of Jews in Atlanta, Georgia. I raised the topic of the murder of Leo Frank.

There was an awkward silence. I had unwittingly committed a faux pas. My friends told me that generations of Atlanta Jews had simply not talked about Leo Frank. In Atlanta-style Yiddish, the entire topic was “shushkied.”

“It’s too raw. It’s too fresh,” one of them said.

That was 90 years after it happened.

The most authoritative book on the Leo Frank case is Steve Oney’s “And the Dead Shall Rise.” Leo Frank grew up in Brooklyn and attended Pratt Institute and Cornell University. His uncle, Moses Frank, invited him to manage the National Pencil Company in Atlanta. In 1910, he married Lucille, who came from a prominent Atlanta Jewish family, and two years later he became president of the B’nai B’rith Gate City Lodge. Their home was in the middle of what is now Turner Field.

In August 1913, a 13-year-old worker, Mary Phagan from Marietta, Georgia, was found murdered in the National Pencil Company’s factory. As a Northerner and a Jew, Frank was automatically, and doubly, the Other and automatically the suspect.

Frank was arrested for the crime and brought to trial. As with the Dreyfus trial in France 20 years before, the mob in the street screamed: “The Jew is the synagogue of Satan!” “Crack that Jew’s neck!” “Hang that damned sheeny!'” Their main inspiration was the famous Georgia politician, Tom Watson, a populist who called for Frank’s lynching — writing, as Mark Twain sardonically put it, “with a pen warmed in hell.”

The jury needed less than four hours to convict Frank. He was sentenced to death. A round of appeals lasted nearly two years. The case became a cause celebre. It involved a number of national Jewish organizations, as well as public figures like Thomas Edison, Henry Ford (before he turned to his own form of Jew-baiting), and New York Times publisher Adolph Ochs, himself a Southern Jew. Ochs had been wary of making the Frank case into a specifically “Jewish” case, but ultimately the Times became the standard bearer in the press, even to the point of being construed as one-sided.

When Frank finally lost the appeal, Georgia Governor Frank Slaton commuted his death sentence to life imprisonment. Ultimately, Slaton had to flee Georgia because of the many death threats against him. He had always believed the truth would come to light and that Leo Frank would be vindicated and released.

It was not to be. Leo Frank was transferred to the state prison farm at Milledgeville, southeast of Atlanta.

On the afternoon of August 16, 1915, a group of 25 men drove from Marietta, northwest of Atlanta, to Milledgeville. It was to be a long ride over coarse roads. They did several trial runs.

They broke into the prison farm. They abducted Frank, kidnapping him — the only time this ever happened in the history of the American penal system.

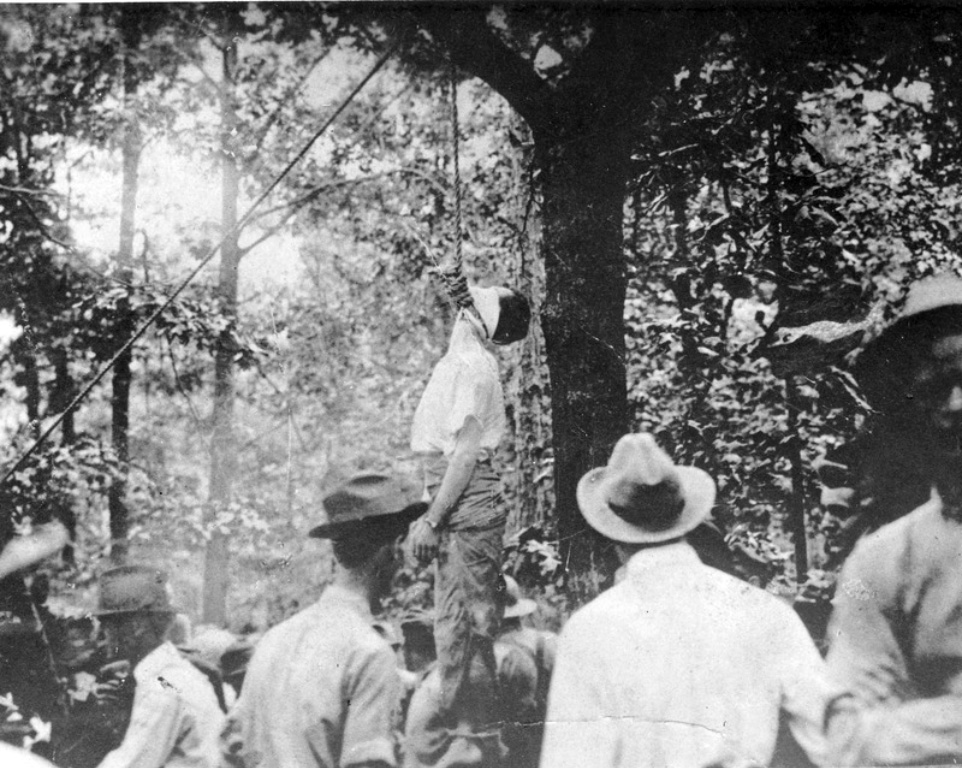

Early the next morning, they hanged Leo Frank from a massive oak tree in Marietta, Georgia, which is now an upscale suburb of Atlanta.

View of the aftermath of the lynching of Leo Frank in Marietta, Georgia, on Aug. 17, 1915. Image courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center via Digital Library of Georgia.

It took Leo Frank nearly 10 minutes to die. The murderers posed proudly with the corpse, still hanging from the tree.

Those photographs became postcards. They were sold as souvenirs. So were pieces of the rope they used in the lynching.

Frank was buried in Mount Carmel Cemetery in Queens, New York.

In the wake of the lynching, there was a wave of anti-Jewish violence in Atlanta and Marietta. Jewish merchants were expelled from Marietta. Many Jews fled Atlanta, never to return.

The Leo Frank case had its afterwaves. It instantly became part of Southern folk culture. Fiddlin’ John Carson, the first commercially successful hillbilly recording artist, composed and recorded an entire genre of Mary Phagan-themed songs: “The Ballad of Mary Phagan,” “Little Mary Phagan,” “The Grave of Little Mary Phagan,” and “Dear Old Oak in Georgia.” These were hit songs; their audiences constantly heard the story, which reinforced their antisemitic views.

The Leo Frank case spawned the creation of two diametrically opposed organizations. It helped create the Anti-Defamation League, America’s foremost civil rights organization. Almost simultaneously, a group that fancied itself the Knights of Mary Phagan gathered at Stone Mountain in Georgia — the “Mount Rushmore of the Confederacy” — and there they revived the Ku Klux Klan.

In 1983, 85-year-old Alonzo Mann, who had been Frank’s office boy, finally admitted a 70-year-old secret: Frank had not killed Mary Phagan.

Why is this story still so important? Because it is a primer on antisemitism.

The Leo Frank case has it all.

- The Leo Frank case was a taste of medieval antisemitism. It conjures up memories of the blood libel and other anxieties about Jews.

- It was a taste of early modern antisemitism. Leo Frank was an urban Jew; Mary Phagan was a farm girl. The story presented the Jew as the symbol of industrialization and of uncontrolled economic change.

- It was a premonition of the Shoah. Men in suits both planned and did the killing, and they stood proudly before their demonic handiwork. Leo Frank’s murderers were not stereotypical ignorant hillbillies. They were community leaders — among them, a judge. They were from prominent families. As Chris Browning made clear in his studies of the Shoah, “ordinary men” are capable of perpetuating great horrors.

- It was a foretaste of modern American Jew-hatred. There is a straight trajectory from the mob calling for Frank’s death to the crowd in Charlottesville chanting, “The Jews will not replace us!” and to QAnon — and yes, to J.D. Vance and Doug Mastriano’s vile antisemitism, and to the Proud Boys and to Jan. 6.

It is all there. And it is all real.

There is now a monument near the inside entrance of the Mount Carmel Cemetery in Queens, near where Leo Frank is buried.

As for his widow, Lucille Frank, she lived to a ripe old age. She is buried in a cemetery in Atlanta. The marker on her grave is small and unobtrusive. For years, no one wanted to publicize its presence, for fear that it would turn into a rallying place for the KKK.

In his essay “Vanadium,” the late Italian-Jewish Holocaust survivor and chemist, Primo Levi, wrote of a problem that he encountered in his work — a varnish that would not dry because it lacked a certain element. (The essay appears in the collection “The Periodic Table.”)

After a prolonged search, Levi received a letter from a Dr. Muller, informing him he worked for a certain German chemical company, and they could supply the missing element.

The name “Dr. Muller” awakened something in Levi’s memory — a memory that, like the varnish, could not dry. “Dr. Muller” had been the name of the overseer who had been in charge of the Buna factory near Auschwitz, where Levi had been interned during the war.

This discovery prompted a correspondence between the two men — once enemies, now colleagues. The correspondence, though somewhat stilted, was cordial. Muller told Levi he had always liked him and was pleased to know he had survived.

For Levi, the varnish that would not dry was not merely varnish. It is a metaphor for the memory of the Shoah — a memory that simply will not go away.

For American Jews, antisemitism is the varnish that will not dry. It is perpetually on the walls of our memories and experiences, and it is perpetually sticky.

A postscript.

Years ago, I knew a man in Atlanta who had an interesting personal custom.

Every year on the anniversary of Leo Frank’s death, he lights a yahrzeit candle for him — as if Frank had been a member of his own family.

When he attends yizkor services on Yom Kippur, he says kaddish for Leo and Lucille Frank, along with the names of his parents and other departed relatives.

Why?

“Leo and Lucille never had children. So I guess that I adopted them. Their memory is my responsibility now.”

And ours, as well.