(RNS) — When a pope resigns or dies, church law mandates that cardinals gather in Rome within 15 to 20 days to elect a new pope. The cardinals decided to meet on May 7, 16 days after the death of Pope Francis because the Vatican needed time to prepare for the 135 cardinal electors, the largest conclave in history.

The meeting of cardinals to elect a pope is called a conclave, from the Latin for “with a key,” since the election traditionally takes place behind locked doors — for generations of cardinals now, the locked doors of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican.

The key to the Sistine chapel and the envelope in which it is sealed. (Photo by Chris Warde-Jones)

Only cardinals under 80 years of age may vote at a conclave. Technically they can elect any male as pope as long as he is, or is willing to be, baptized and ordained a priest and bishop. However, it has been more than 600 years since someone who is not a cardinal has been elected.

The cardinal electors live in Domus Santae Marthae, a residence inside the Vatican, a short walk from the Sistine Chapel. Before the cardinals enter the conclave, the chapel is swept for electronic bugs. Only the cardinals may be in the Sistine Chapel as the voting takes place, but they are attended by a small number of confessors, medical staff and liturgical assistants, as well as cooks and housekeeping staff. These helpers must swear to maintain secrecy about what happens in the conclave.

FILE – The Domus Sanctae Marthae in Vatican City, where cardinal electors stay during the conclave. (Photo by Rene Shaw)

If the cardinals follow the same schedule as last time, they will meet in the Sistine Chapel from about 4:30 to 7:30 p.m. on the first day of the conclave. There are no speeches or debates — in fact no talking at all except what is required for the oaths and the counting of the ballots. All discussion and politicking take place outside of the Sistine Chapel.

Besides an oath to observe the rules set down for the conclave, the cardinals swear to maintain the secrecy of the conclave and to not follow any instructions from secular authorities. And if elected pope, they promise to protect the liberty of the Holy See.

The electors also hear in that first meeting from a cleric previously chosen to preach on “the grave duty incumbent on them and thus on the need to act with right intention for the good of the universal church.” After he finishes, he and anyone who is not a cardinal elector must leave the chapel.

A vote can occur on the first afternoon of the conclave, but at the last conclave, in 2013, no vote took place on the first day. It takes a two-thirds vote of those present to elect a pope.

The cardinals recite vespers together at the conclusion of each day if a pope is not elected.

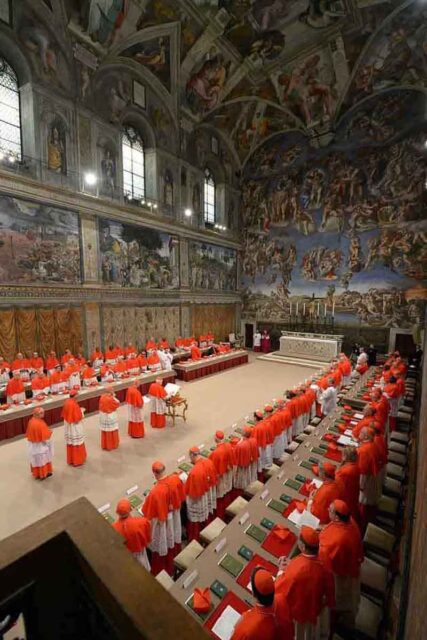

FILE – Cardinals line up in the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel, March 12, 2013, to take their oaths at the beginning of the conclave to elect a successor to Pope Benedict XVI. (Photo by Vatican Media)

The second day begins with Mass at 8:15 a.m. in the Pauline Chapel, followed at 9:30 by mid-morning prayer from the Divine Office and voting in the Sistine Chapel. If no one is elected, they break at 12:30 for lunch and return at 4:50 for more voting until about 7:30.

There are usually two votes in the morning and two in the evening.

The voting is highly choreographed to avoid any possibility of fraud or doubt about the results. The cardinals want no possibility of a candidate challenging the election results.

At the last conclave, the cardinals sat according to seniority behind four rows of tables, two on each side of the chapel. They will need more chairs because of the larger number of cardinals. At each place is a pen and ballots on which each elector writes the name of his choice. The ballot is a rectangular card with “Eligo in summum pontificem” (“I elect as supreme pontiff”) printed at the top. When folded down the middle, the ballot is only 1-inch wide.

Before voting, three “scrutineers” are chosen by lot from the electors to count the ballots, with the least senior cardinal drawing the names. He draws three additional names of cardinals (called infirmarii) who will collect the ballots of any cardinals in the conclave who are too sick to come to the Sistine Chapel.

A final three names are drawn by lot to act as revisers, who review the work done by the scrutineers. Each morning and afternoon, new scrutineers, infirmarii and revisers are chosen by lot.

Each cardinal prints or writes the name of his choice on the ballot in a way that disguises his handwriting, to maintain the secrecy of the ballot. One at a time, in order of precedence, the cardinals approach the altar with their folded ballot held up so that it can be seen.

After kneeling in prayer for a short time, the cardinal rises and swears, “I call as my witness Christ the Lord who will be my judge, that my vote is given to the one who before God I think should be elected.” He then places the ballot in a silver and gilded bronze urn shaped like a wok with a lid.

Urns used for collecting ballots. (Video screen grab)

There is a second smaller urn used by the infirmarii to collect ballots cast by cardinals too ill to go to the Sistine Chapel.

The first scrutineer shakes the urn to mix the ballots, to preserve anonymity. The last scrutineer counts the ballots before they are unfolded. If the number of ballots matches the number of electors, the scrutineers, who are sitting at a table in front of the altar, begin counting the votes. If the number of ballots does not correspond to the number of electors, the ballots are burned without being counted and another vote is immediately taken. This actually happened during the election of Pope Francis when a cardinal mistakenly put a blank ballot in the urn along with his ballot.

The first scrutineer unfolds the ballot, notes the name on a piece of paper and passes the ballot to the second scrutineer. He notes the name and passes the ballot to the third scrutineer, who reads it aloud for all the cardinals to hear. If there are two names on a single ballot, the ballot is not counted.

The last scrutineer pierces each ballot with a threaded needle through the word “Eligo” and places it on the thread. After all the ballots have been read, the ends of the thread are tied together and the ballots thus joined are placed in a third urn. The scrutineers then add up the totals for each candidate.

FILE – The stoves in the Sistine Chapel where ballots are burned twice a day, around noon and 7 p.m., unless a pope is elected on an earlier ballot. Chemicals are added to make the smoke white or black. (RNS photo/David Gibson)

Finally, the three revisers check both the ballots and the notes of the scrutineers to make sure that they performed their task faithfully and exactly. Thus, six cardinals, chosen by lot, review each ballot in front of the cardinals before the results are announced. There can be no talk of a stolen election.

The ballots and notes are then burned in a special stove installed in the Sistine Chapel, unless another vote is to take place immediately. The ballots are burned by the scrutineers with the assistance of the secretary of the conclave and the master of ceremonies, who adds special chemicals to make the smoke white or black. Since 1903, white smoke has signaled the election of a pope; black smoke signals an inconclusive vote. At the last conclave, the ringing of the largest bell at St. Peter’s was added to the white smoke as a signal that a pope was elected.

Black smoke will appear around noon and 7 p.m. from the stove until a pope is elected. White smoke could appear at these times or earlier, around 10:30 a.m. or 5:30 p.m., if a pope is elected on the first ballot of the morning or afternoon.

The only written record of the voting is a summary of each session prepared by the camerlengo, who runs the church during the sede vacante — the period of an “empty seat” between popes. It is approved by the three cardinal assistants and given to the new pope to be placed in the archives in a sealed envelope that may be opened by no one unless the pope gives permission.

If after three days the cardinals have still not elected anyone, the voting sessions can be suspended for a maximum of one day for prayer and discussion among the electors. During this intermission, a brief spiritual exhortation is given by the senior cardinal deacon. Then another seven votes take place, followed by a suspension and an exhortation by the senior cardinal priest. Then another seven votes take place, followed by a suspension and an exhortation by the senior cardinal bishop. Voting is then resumed for another seven ballots.

To go through this process would take about 13 days. In the recent past, conclaves have not lasted more than a few days, though there is no set time for the cardinals to finish.

If no candidate received a two-thirds vote after the 13 days of balloting, a runoff takes place between the top two candidates. However, since a two-thirds vote is still required to elect a pope, this innovation instituted by Pope Benedict XVI could result in a deadlocked conclave with no possibility of finding a third compromise candidate.

Benedict’s innovation replaced the change instituted by Pope John Paul II that would allow a simple majority of the cardinals to suspend the two-thirds requirement at this point in the conclave. John Paul’s change made it difficult to stop a candidate once he received a majority vote.

John Paul and Benedict appear to have feared that a long conclave would scandalize the faithful and be detrimental to the church, but their solutions caused other problems. The old rules forced the cardinals to compromise and look for a consensus candidate.

Benedict’s innovation could result in a deadlocked conclave if more than a third of the cardinals vehemently opposed both candidates. Benedict’s new rule does not explain what to do if two candidates are tied for second place.

After being elected pope in 2013, Francis said that he had received 40 of 115 votes at the previous conclave in 2005. Under the old rules that would have stopped the election of Cardinal Josef Ratzinger (as Benedict XVI), unless some of his voters switched to Ratzinger. Under the new rules, the Ratzinger voters simply had to stick to their man until they could suspend the rules and elect him with a majority vote. Francis put a stop to the delay by telling the cardinals that he supported Ratzinger and would not accept the papacy if elected.

Once a pope is elected, the dean of the College of Cardinals asks the man, “Do you accept your canonical election as supreme pontiff?” If he is a bishop and agrees, he is immediately pope. If he is not a bishop, he would have to be ordained a bishop before becoming pope, since the pope is the bishop of Rome. The British priest Timothy Radcliffe, who was made a cardinal by Francis, is the only elector who is not a bishop.

When Cardinal Giovanni Colombo, a 76-year-old archbishop of Milan, began receiving votes during the conclave in October 1978, he made it clear that he would refuse the papacy if elected.

The dean also asks by what name the pope wishes to be known.

The first pope to change his name was John II in 533. His given name, Mercury, after the Roman deity, was considered inappropriate. Another pope took the name John XIV in 983 because his name was Peter and people did not think it right for him to share the name of the first pope.

At the end of the first millennium, a couple of non-Italian popes changed their names to ones that the Romans could more easily pronounce. The custom of changing one’s name became common around the year 1009. The last pope to keep his own name was Marcellus II, elected in 1555.

Once the pope has accepted and named himself, the cardinals approach the new pope and make an act of homage and obedience. A prayer of thanksgiving is said, and the pope changes from his cardinal robes to the white papal cassock. In the past, the pope was presented in full papal regalia, with the red velvet mozzetta trimmed with ermine. But Francis only wore a simple white cassock with a simple metal cross.

Meanwhile, the people of Rome are rushing to St. Peter’s Square to see the pope and get his first blessing.

When the pope is ready, the senior cardinal deacon informs the people in St. Peter’s Square that the election has taken place and announces the name of the new pope: “Habemus Papam,” Latin for “We have a pope.”

The pope then may speak to the crowd and grant his first solemn blessing “urbi et orbi” — to the city and the world.