President John F. Kennedy. John Lennon.

If you are of a certain age, you remember where you were when you learned of the untimely deaths of those iconic figures.

But, JJ Goldberg adds one more icon to that list: the protest-“topical” singer-songwriter, Phil Ochs, who died exactly forty years ago this week — a death by suicide, after years of struggling with alcoholism and mental illness. He was 35 years old.

I know exactly where I was when I heard about Ochs’ death — a Reform Jewish college seminar at the Eisner Camp in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. The news had come on Shabbat, and it darkened Shabbat for all of us. That Ochs was Jewish made the news darker still.

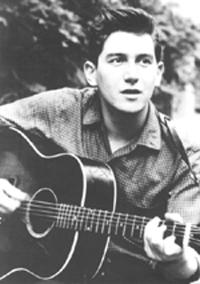

I cannot imagine my teen years without the musical presence of Phil Ochs. He was my musical hero.

It is sometimes difficult to remember how ubiquitous topical music was in those days. We can almost laugh at it now; check out the Coen Brothers’ film Inside Llewyn Davis, or A Mighty Wind.

Nothing escaped Phil Ochs’ eye. He was a combination journalist-songwriter (for which Bob Dylan once savagely attacked him) — which is why one of his early albums was named All The News That’s Fit To Sing. His topics:

- Civil rights — “Here’s To The State of Mississippi.”

- The war in Viet Nam — too many to list, but “I Ain’t Marching Anymore” stands out.

- American foreign policy — “Cops of the World.”

- The draft —“”Draft Dodger Rag.”

- Campus protests — “I’m Gonna Say It Now.”

- The brief 1965-1966 American military adventure in the Dominican Republic — “Santo Domingo.” it is possible that more people remember Phil’s song than actually remember that mini-war.

- The plight of migrant workers — “Bracero.”

- Religious hypocrisy — “The Cannons of Christianity.”

Two of his topic songs stand out — in ways that still speak to us.

Take “Love Me, I’m A Liberal.” It was his snarky response to so-called liberals, who professed all of the right positions (nowadays, some would call it political correctness), but who balked at anything that would affect them personally. Listen to the song; you would need an annotated lyrics sheet in order to get the half-century old political and cultural references — to such people as “Harry” (Belafonte) and “Sidney” (Poitier) and “Sammy” (Davis, Jr.), Hubert Humphrey, and Les Crane, a by-now almost forgotten television talk show host.

And then, there’s his classic, often quoted “Outside of a Small Circle of Friends.” The song was inspired by the infamous 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese in Queens, who died while her neighbors watched. Last week, Ms. Genovese’s murderer, Winston Moseley, died in prison. The Genovese murder became a metaphor for urban apathy, and the song famously expanded the implications of that murder into a commentary on the human condition of massive indifference to anything that goes beyond ourselves.

Oh, how we loved Phil Ochs. We sang his songs on basement rec room floors; I learned to play guitar by learning to play his songs. We sang his songs in Jewish youth group. We sang his songs at Jewish summer camp.

Phil Ochs made protest respectable. He was never a hippy. He, alone of that entire 1960s musical crew, never grew his hair long. He often wore a suit when he performed. And he loved America with a fierce Woody Guthrie-like patriotism; he wanted her to be better.

Some of his non-topical songs are still startling in their beauty. At summer camp, we could sing “Changes” by heart. Listen to “There But For Fortune.” At my confirmation service, I sang “When I’m Gone” right before Kaddish; I dare you to listen to it without weeping (and yes, that is the late Robert Kennedy speaking in the background).

But, Phil could be wrong, as well — and his errors, like his music, have had an active shelf life.

On the back of his 1966 album “Phil Ochs In Concert” (exactly fifty years ago), Phil insisted on reprinting eight poems by the Chinese Communist dictator, Mao Zedong. His comment on the poems? “Could this be the enemy?”

Phil Ochs was wrong. Yes, this was the enemy. It did not matter how beautiful his poetry was. Mao was personally responsible for the killing of an estimated 45 million of his own countrymen.

Phil Ochs’ intellectual and philosophical error was simply this: confusing aesthetics (that which is beautiful) for ethics (that which is right). And when we put aesthetics over ethics, we are committing a particularly savage form of idolatry.

None of this dampens my love for Phil Ochs. His decline and ultimate death was an American tragedy.

Forty years later, he still speaks to us.

“In such an ugly time, the true protest is beauty,” he wrote.

Our time is no less ugly. We can only wonder what Phil would have been singing about today.

Let the beauty of the word and of the inner beatings of the soul be our true protests.