LAS VEGAS (RNS) — Imam Fateen Seifullah wants to transform Sin City into the City of Light.

The imam, who leads Masjid As-Sabur, the oldest mosque in the Las Vegas area, is quick to clarify: “Not casino lights — I’m talking about noor,” he said, using the Arabic word for light that Muslims often use to refer to God’s divine presence.

Since 2010, Seifullah has led an initiative to develop what he calls a “Muslim Village,” just miles north of the glitz and hedonism of the Strip. His congregation has slowly but surely driven local drug houses and gangs out of the historic neighborhood known as West Las Vegas. Now, the mosque is on a mission to purchase the surrounding properties and transform them into affordable housing.

“The Muslim Village was started as a safe space for the local Muslims and non-Muslims,” Seifullah said, showing off a colorful mural painted on one of the mosque’s walls by one of the Muslim Village’s elderly residents. “Our goal has been to leave a positive physical imprint on the environment, so when people look at it they see what the Muslims have done here.”

While properties were often becoming available, few Muslims in the area saw any value in them — until the imam, who says new construction has an uplifting psychological impact, reframed the development effort as a 10-year project to create a transformative Muslim community.

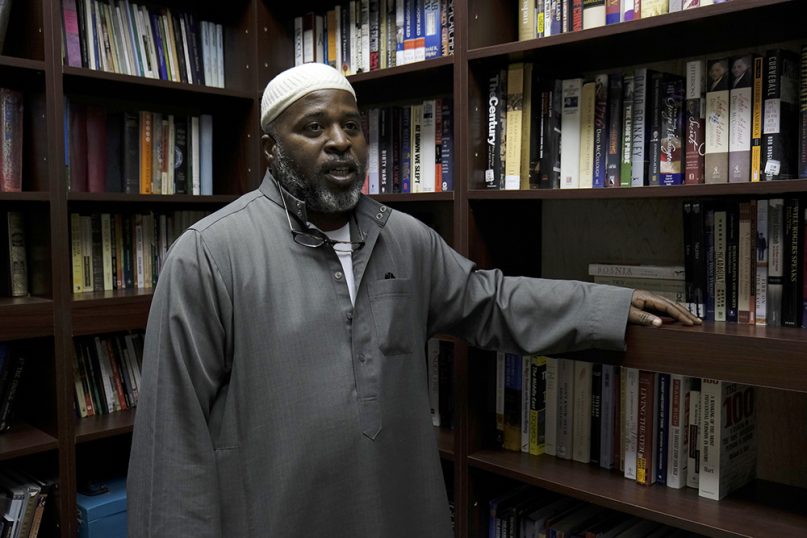

Imam Fateen Seifullah shows the library in the Muslim Village in Las Vegas. RNS photo by Aysha Khan

Inside the growing “village” are a free medical clinic, a food pantry, a library, a community garden and a Monday-through-Friday school for youth. The mosque also provides meals, temporary housing for women facing abuse or other issues, short-term rent and utilities assistance, and a faith-based 12-step program to recover from addiction. By next year, Masjid As-Sabur hopes to expand beyond one- and two-bedroom apartments to begin constructing townhomes on the vacant lot beside the mosque.

“Initially the goal was to invigorate the community when it came to purchasing and developing property in this community that had been neglected and is so depressed,” Seifullah explained.

All the facilities and services are available to anyone of any faith who is in need. A third of the approximately 20 Muslim Village renters, most of whom are college students, women and seniors, are not Muslim.

For over a decade, the mosque has also brought together hundreds of local volunteers to arrange an annual Day of Dignity event. Led by the national Islamic Relief USA organization, which has donated to Masjid As-Sabur as part of its domestic charity program, mosques around the country spend one day a year providing hot meals, school supplies, hygiene kits, clothes, medical care and other resources to those in need, according to the organization’s website. This year’s event is scheduled for Oct. 26 in Vegas.

For Masjid As-Sabur, though, the work of service never ends.

Masjid As-Sabur, the oldest mosque in the Las Vegas area. RNS photo by Aysha Khan

Situated in the neighborhood around Washington Avenue and H Street, Masjid As-Sabur sits just across the street from the city’s public housing projects, where the mosque hosts a regular chess club.

“The need is surrounding us,” the imam said. He paused to greet a Muslim Village resident making his way to the mosque to perform his ablutions.

“It’s easy to do what we do to follow the path of our faith. The real tragedy is that we’re just a quarter mile from all this wealth and extravagance. The homeless and hungry are just around the corner from buffets where they throw away food.”

Women leaders of Masjid As-Sabur with a police officer from the Bolden area command in Las Vegas. Photo courtesy Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department

After Seifullah launched the Muslim Village project, the city of Las Vegas designated the area, which has one of the city’s highest homeless populations, a crime- and drug-free zone.

To Afsha Bawany, a native Las Vegan Muslim who has researched faith groups’ impact on community resilience, Masjid As-Sabur exemplifies community support.

“Masjid As-Sabur is an integral part of helping our community stay resilient and helping address economic distress, homelessness and violence prevention,” Bawany, who volunteers with the mosque, said. “It’s part of a network of volunteers that makes sure those who are most vulnerable in Southern Nevada are taken care of. They’re a prime example of what it means to live your faith.”

Over the past decade, Seifullah said, the neighborhood has become much quieter and sees less crime. The Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, whose officers visit the congregation weekly and have participated in the mosque’s Day of Dignity events, said it could not provide data on crime rates but noted that neighborhoods with more active communities are linked to less crime.

The annual Day of Dignity event hosted by Masjid As-Sabur in Las Vegas. Courtesy photo

“There’s a bond that’s developed between our officers and the mosque,” Aden Ocampo-Gomez, public information officer for the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, told Religion News Service. “Some of the officers in that area command sometimes stop by just to stop by. Not because something bad is going on, but just to hang out, talk, play with the kids and be part of the community.”

The mosque’s services are especially critical at a time when the City Council has proposed criminalizing camping, sleeping, sitting and lying down in the city’s public spaces downtown and in residential neighborhoods.

“The city officials and police have taken more of an interest in seeing this area transformed rather than just policing it aggressively,” Seifullah said. “We’ve made inroads into the community, into the heart of the projects, where gang members consider us extensions of their family. The people know us and trust us.”

While other Muslim neighborhoods in the U.S. and Canada, from upstate New York’s Islamberg community to suburban Maryland’s Ansar Peace Village, have faced backlash from some residents, Seifullah said the Muslim Village project has been welcomed with open arms by the local community.

The Muslim Village plans to build a transformative community in the West Las Vegas neighborhood. RNS photo by Aysha Khan

The blocks surrounding the mosque are scattered with churches of various stripes. The mosque is neighbored by an Episcopal church and frequently partners with it for service projects.

On the other side of the mosque is a fourplex owned by a Jewish landlord, who painted his building white with emerald green trim to mirror the mosque’s adobe-style aesthetic.

“We’re an extension of this neighborhood,” Seifullah said. “Not just after 9/11 but every time there’s some incident and Muslims feel threatened, neighbors assure us they’re keeping an eye on this place for us.”

In turn, he said, locals know they can rely on Masjid As-Sabur as a safe space for shelter and support. Many of the local gang members are respectful of the mosque’s space, knowing their parents often turn to the mosque for food baskets and other social services.

“People who are neglected, people who come here for gaming and then lose everything and just need a bus ride home, they walk here because they believe they can get help here,” he said, recalling an incident when a man was shot in the projects and came to the mosque seeking assistance. “They say, ‘If anybody can help you, it’s the Muslims, go see them.’”

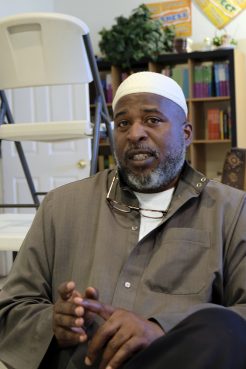

Imam Fateen Seifullah discusses his plans for transforming West Las Vegas. RNS photo by Aysha Khan

Faith is in Seifullah’s blood: Two of his brothers are Church of God pastors. The Louisiana native was raised in a Southern Baptist church but was drawn to the Nation of Islam’s black nationalist teachings while growing up in Los Angeles’ Compton neighborhood. In 1988, Seifullah joined Imam Warith Deen Mohammed’s movement, attracted by the faith’s promotion of discipline and brotherhood.

Seifullah began instituting social service projects at the mosque in 1999, when he joined as its imam. He was inspired by influential imam and civil rights activist Jamil Al-Amin’s work reducing crime and gang activity and revitalizing Atlanta’s impoverished West End neighborhood. (Al-Amin, who led one of the country’s largest black Muslim groups, is currently serving a life sentence for the shooting of two police officers. Many civil rights activists and American Muslims see his conviction as an anti-black and anti-Muslim conspiracy.)

Masjid As-Sabur has ministered to a handful of Muslim figures with household names, including Mike Tyson, Muhammad Ali and the boxer’s daughter Laila Ali. Tyson, who was known for regularly helping vacuum the mosque’s rugs, donated $250,000 to the construction of the current mosque — more than half the cost of the work — in 1997. Muhammad Ali helped with fundraising for the same project.

Like Seifullah, the mosque emerged out of the Nation of Islam. In 1975, after NOI founder Elijah Muhammad’s death, the local African American Muslim community in Vegas split apart, mirroring a national fissure. A faction followed his son, Imam Warith Deen Mohammed, into the broader Sunni tradition of Islam. In 1982, the new community built its own mosque, originally called Masjid Muhammad. The original Nation of Islam temple, Muhammad Mosque #75, founded in the 1960s and now under the national leadership of Louis Farrakhan, is a short walk away on D Street.

“You can hear the sound of adhan here for 25 years or so in this neighborhood,” Seifullah said, the sound of the Arabic call to prayer echoing from the mosque’s speakers. Residents of the Muslim Village begin emerging from their front doors, heading toward mosque to perform their ablutions for the zuhr prayers.

Today, Masjid As-Sabur’s congregation is a mix of African Americans, immigrants and converts of various backgrounds. They’re part of Vegas’ thriving, close-knit Muslim community, which falls somewhere between 10,000 and 20,000 in size, per various estimates.

“People don’t believe that there are Muslims who reside in Vegas,” Seifullah said. “But we’re here. We’re giving hope to people who have lost hope for all sorts of reasons.”